A nation must think before it acts.

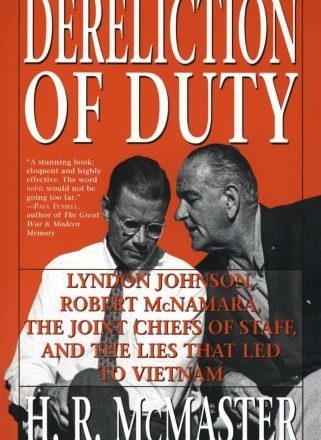

REVIEW: H.R. McMaster, Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam (Harper Perennial, 1998).

Dereliction of Duty is a serious book. Thoroughly researched, carefully argued, it tackles a big subject: Who is responsible for the debacle that is the Vietnam War? McMaster concludes that everyone in political and military leadership was: Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, presidential military advisor Maxwell Taylor, the Congress and — especially — the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He’s not wrong, but this book by the man who recently became President Donald Trump’s national security advisor reveals an innocence about politics at the highest levels as well as some questionable judgments about civil-military relations in the United States.

The book begins with the debacle that was the Bay of Pigs, which soured Kennedy on the judgment of his military leadership. Not long after, the Cuban missile crisis saw the military completely excluded from decision making. By the time the administration got to Vietnam, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were marginal to policy formation and major decisions. Johnson’s unexpected ascension thrust great responsibility onto an inexperienced and insecure political leader with ambitious domestic policy plans and wariness of looking weak on international issues.

The book reads like a tragedy. Political choices led to an ill-advised commitment that the White House considered too costly to either fully admit or renege on. The Joint Chiefs saw the mistakes but felt they had little influence to correct course. Instead, they tried trimming their sails to meet the politicians’ preferences, resigning themselves to try and make a bad strategy successful. And therein lies the interesting civil-military issue: Should the Chiefs have openly defied the president? McMaster believes they were derelict in their duty for not insisting on the superiority of their views and publicly revealing the inadequacies of the president (his concluding chapter is titled “Five Silent Men”). But the case is grayer than he admits.