A nation must think before it acts.

China’s New Missiles and U.S. Alliances in the Asia-Pacific: The Impact of Weakening Extended Deterrence

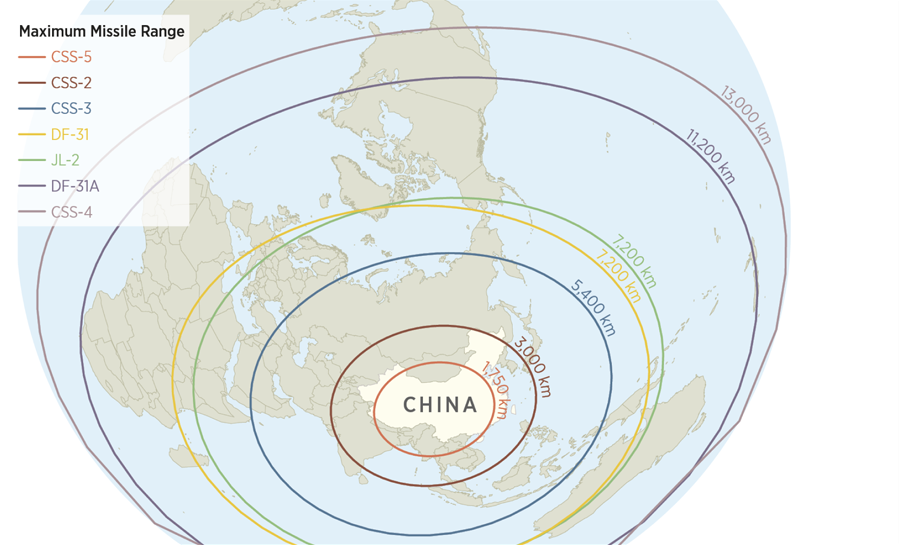

Two weeks ago, Chinese President Xi Jinping attended a nuclear security cooperation summit in Washington. At the same time, China has been busily preparing its next generation of nuclear weapons. It has made steady progress on its new DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Last December, China conducted two more tests on the missile, including one that confirmed the DF-41’s ability to be launched from a mobile platform. The DF-41 will be China’s first solid-fueled missile with the range to reach the entire continental United States. The new missile’s range will likely exceed that of China’s older liquid-fueled DF-5 (or CSS-4 according to its NATO designation) ICBM. As a mobile, solid-fueled missile, the DF-41 will be hard to track and able to quickly launch, improving China’s nuclear deterrent. Some believe that China might deploy the DF-41 as early as this year.[1]

China has also been developing a sea-based ICBM, the JL-2. Though the JL-2 has a shorter range than the DF-41, China has built four Jin-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines to carry JL-2 missiles closer to their targets. While those submarines are unlikely for the moment to venture far from their base at Yalong Bay on Hainan Island, American officials confirmed that one of them conducted a patrol late last year. [2] Whether or not JL-2 missiles were on board the submarine is unknown. But if they were, that would make the JL-2 even more elusive than the DF-41, again strengthening China’s nuclear deterrent.

While China’s nuclear arsenal is small when compared to those of Russia or the United States, there is little doubt as to its enduring importance to Beijing. That much is clear in the special status its nuclear weapons program has held over the last half century. As part of its wide-ranging military reorganization early this year, Beijing elevated its land-based nuclear forces, once a component of the army, to a full-fledged service on par with the army called the Rocket Force.

Many Chinese analysts believe that by creating a more robust nuclear retaliatory capability they can ensure that no country would threaten China with nuclear coercion should a crisis erupt over one of its “core interests,” like Taiwan. As one Chinese official once famously quipped in the 1990s, the United States would never trade “Los Angeles for Taipei.” Hence, China has opposed any proposal that might blunt the effectiveness of its nuclear missiles, even indirect ones, like America’s recent effort to deploy its Theater High-Altitude Air Defense system to protect South Korea and Japan from a possible North Korean missile attack. While Beijing may contend that a state of mutual vulnerability would lead to a more stable security environment between China and the United States, it also complicates a key feature of U.S. alliances in the Asia-Pacific.

Since the Cold War, U.S. allies, like Australia, Japan, and South Korea, have enjoyed what is called “extended deterrence”—a security guarantee that the United States would be willing to use its nuclear forces to deter aggression against them. But that guarantee is dependent on the credibility of the United States to act. Naturally, the United States is more likely to act if potential adversaries are unable to retaliate against it. Once fully operational, China’s new missiles, which can directly threaten the United States, will complicate the credibility of America’s security guarantee to its allies, weakening extended deterrence.

Already American credibility to act has been questioned over the last half decade, due to the Obama administration’s repeated hesitancy in foreign crises. The reliability of America’s security commitments concerns many of its allies in the Asia-Pacific, as China’s military capabilities continue to grow. That has led some U.S. allies to reevaluate their own military postures. Japan has even taken steps to change its constitution to enable its military to take on a more “normal” role to safeguard Japanese interests in the region.

Australia has begun to do the same. Since the early 2000s, several Australian policymakers have argued for a more self-reliant defense. In its 2009 defense planning document Australia stated “in terms of military power… we must have the capacity to act independently where we have unique strategic interests at stake.”[3] Then, its defense white paper this year, Australia indicated that it could only assume American military dominance in the Asia-Pacific for the next two decades, rather than for the “foreseeable future” as it had in the past. [4] As a result, Australia is pressing ahead with a defense review that will culminate in the purchase of a raft of new military hardware. Australia is now considering the purchase of Japanese submarines for its navy. A few Australian analysts have even begun to openly wonder whether nuclear weapons should in Australia’s future.

Some American policymakers have welcomed the change that weaker extended deterrence has brought. Long-time issues of burden-sharing have eased. They believe that a web of militarily stronger allies can deter China from upsetting Asia’s regional order and do so at a lower cost to the United States. If they are correct, it may usher in a new era of stability. But it also means that the United States will be less able to manage crises in Asia-Pacific, as regional countries will have greater ability to act without it. Should American allies do so, they could draw the United States into a crisis that it would have rather avoided. For those who are concerned about that prospect, it provides an added incentive to pursue ever stronger anti-ballistic missile defenses.

—

[1] “China’s top new long-range missile ‘may be deployed this year’, putting US in striking distance,” South China Morning Post, Mar. 29, 2016; Bill Gertz, “Chinese Defense Ministry Confirms Rail-Mobile ICBM Test,” Washington Free Beacon, Dec. 31, 2015; Bill Gertz, “China Tests New ICBM from Railroad Car,” Washington Free Beacon, Dec. 21, 2015; Keither Bradsheraug, “China Said to Bolster Missile Capabilities,” New York Times, Aug. 25, 2012, p. A5.

[2] Bill Gertz, “Pentagon confirms patrols of Chinese nuclear missile submarines,” Washington Times, Dec. 9, 2015.

[3] Australian Department of Defence, Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030 (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2009), p. 48.

[4] Australian Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper (Canberra: Department of Defence, 2016), p. 41.