A nation must think before it acts.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) has existed since 1978, but rarely does it prompt the sort of public attention it has received in the past several months. In part, this was an inevitable by-product of the reauthorization debate surrounding FISA Section 702, one of the more controversial elements of FISA’s array of national security authorities. Additional attention also was precipitated by FISA’s rather peripheral role in the ongoing investigation of Russian meddling into the 2016 election.[1] The reauthorization debate concluded with Congress renewing Section 702 for six years and, depending upon the persistence of certain members of Congress, presumably the needless politicization of FISA in the context of investigating Russian election meddling also will mercifully end in the very near future.

Which means that FISA, for all its importance as a foreign intelligence collection tool, is unlikely to remain in the forefront of public consciousness. Before it fades from public attention, however, this is the time of year when the entities statutorily responsible for reporting to Congress on FISA activities announce their numbers, and those reports merit review and some comment.[2]

The Administrative Office of U.S. Courts (AOUSC) was the first to release its Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts on the Activities of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for 2017. The AOUSC reporting mandate is a relatively new requirement imposed by Congress as part of the USA Freedom Act passed in 2015. Consequently, there is a partial report from the AOUSC for 2015, and full-year reports only for calendar years 2016 and, now, 2017. As included in my earlier article published in FPRI’s E-Notes,[3] the AOUSC reported the following:

Commentators seized on these 2017 AOUSC numbers to report a “record” number of FISA “denials” in the first year of the Trump administration,[4] although at least one commentator had come to the same conclusion after reading the AOUSC statistics for 2016—the last year of the Obama administration.[5]

The Department of Justice (DoJ) also furnishes an annual FISA report that has been required since FISA was first enacted in 1978 and, although the statutory language for both the AOUSC and DoJ reporting requirements[6] is substantially similar, the categorizations of the work of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) found in these reports have produced dissimilar statistics in past years. Based on this history, I hypothesized in my May 4, 2017 FPRI E-Notes article that the then-unreleased DoJ report for 2017 FISC activity would likely show considerably fewer than the “record” number of “denials” reported by the AOUSC.

On May 4, 2017, the DoJ Office of Legislative Affairs report for FISC activities for 2017 was publicly released. Regarding electronic surveillance and physical searches pursued under FISA, the DoJ announced:

During calendar year 2017, the Government filed 1,349 final applications to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (hereinafter “FISC”) for authority to conduct electronic surveillance and/or physical searches for foreign intelligence purposes. The 1,349 applications include applications made solely for electronic surveillance, applications made solely for physical search, and combined applications requesting authority for electronic surveillance and for physical search. Of these, 1,321 applications included requests for authority to conduct electronic surveillance.

Two of these applications were withdrawn by the Government. The FISC did not deny any final, filed applications in whole, or in part. The FISC made modifications to the proposed orders in 154 final, filed applications. Thus, the FISC approved collection activity in 1,319 of the applications that included requests for authority to conduct electronic surveillance.[7]

Thus, different definitional constructs have produced very different FISA statistics for 2017 even though the statistics were drawn from the same body of underlying data. As the DoJ report acknowledges, the AOUSC’s methodology yields 1,372 (not 1,349) applications seeking

authority to conduct electronic surveillance and/or physical search with 24 of those applications having been “denied,” 47 “partially denied,” and 353 “modified” using the AOUSC’s counting rubric. The AOUSC produces those numbers by counting “proposed” applications,[8] certain numbers of which, for what the DoJ report describes as “a variety of reasons,” do not come to fruition as “final filed” applications.

Conversely, the DoJ counts only what it describes as “final filed applications” and, using its interpretation of that terminology, reported less than half the number of “modified” applications as the AOUSC while also concluding that no final filed application was denied by the FISC in 2017.

The disparity in the two sets of statistics is certainly notable for 2017, but that same disparity (albeit in a slightly lower order of magnitude) also appears in a comparison of the 2016 FISC numbers which, for now, is the only other full calendar year for which the AOUSC has produced statistics. It seems premature to draw conclusions from this limited data: the differences may be explained as nothing more than variations produced by the different definitional approaches. Or, perhaps, the numbers do reflect an increasingly aggressive use of national security authorities bumping against a FISC that is vetting government applications with increased scrutiny and the assistance of amicus curiae counsel appointed since passage of the 2015 USA Freedom Act. Or, as the DoJ suggests in its report, the contrast is simply the product of “the robust interaction between the Government and the Court”[9] in applying the surveillance authorities found in FISA. A more informed analysis must await additional data detailing future FISA activities.

Congress also requires that the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) release an annual report which the DNI styles as its Statistical Transparency Report, and the 2018 version of the DNI’s report (publicly released on May 4, 2018) is worthy of review before closing the book on FISA’s annual reporting season. In that 2018 version, reporting on 2017 FISA activity, the DNI clearly utilizes the DoJ approach to counting as it reports a total of 1,437 “probable cause” FISA orders. This is more than the 1,349 “final filed” applications reported by the DoJ, but the difference is accounted for by subtracting the two final filed applications that the DoJ reports as withdrawn, and then adding an additional 90 orders entered under Section 704 of FISA, which covers the targeting of U.S. persons outside the United States where the collection occurs outside the United States.[10]

The DNI totals for “traditional FISA” generally more closely resemble those reported by the DoJ as opposed to those issued by the AOUSC, but the DNI also reports more expansively on other FISA authorities than does the DoJ in its annual report. For example, the DNI report includes statistical data on physical searches, pen registers/trap and trace devices, orders for the production of business records, and on electronic surveillance conducted under FISA Sections 702, 703, and 704. The DoJ reports on none of these particular FISA authorities in its annual § 1807 report because Congress has never expanded the requirements in § 1807 beyond providing the number of applications for electronic surveillance “under this subchapter.” “This subchapter” is Subchapter I of FISA which covers only “traditional FISA” extending to FISA orders based on probable cause covering foreign intelligence electronic surveillance conducted in the United States.

Conversely, the annual DNI reporting mandate is codified in 50 U.S.C. § 1873(b) and calls for statistical data not only regarding FISA Subchapter I electronic surveillance but also for: (1) physical searches conducted under FISA Subchapter II; (2) electronic surveillance conducted pursuant to FISA Sections 702, 703, and 704 (Subchapter VI); (3) pen register and trap/trace device orders under Subchapter III of FISA; (4) business record production orders issued under the authority provided in Subchapter IV of FISA; and (5) the use of U.S. Person identifiers as search terms.

The broader DNI reporting requirements for the most part mirror those required of the AOUSC (codified in 50 U.S.C. § 1873(a)). The similarities are probably attributable to both of those §1873 reporting mandates having their origins in the USA Freedom Act passed in June 2015 when Congress sought to improve oversight through more detailed reporting in the aftermath of :(1) the expansion of FISA authorities under the original 2008 FISA Amendments Act; and (2) the 2013 disclosures made by Edward Snowden. For reasons not immediately apparent from the disparate pieces of legislation containing the various reporting requirements, Congress did not expand the reporting mandate required of the DoJ found in § 1807. Instead, 50 U.S.C. § 1871 requires that the DoJ report “on a semiannual basis” on the same expanded category of FISA authorities (i.e., physical searches, pen registers, business record demands, and Section 703 and 704 electronic surveillances) that § 1873 requires both the DNI and the AOUSC to disclose on an annual basis. However, the DoJ’s § 1871 mandate specifically provides that the reporting be done “in a manner consistent with the protection of the national security” and, accordingly, § 1871 reports are generally heavily redacted.

These 1,437 orders reported by DNI (i.e., Subchapter I plus Section 703 and 704 FISA orders) cover 1,337 targets, of which 299, or 22.4%, are U.S. Persons. While the number of orders and the number of targets are less than reported by the DNI for 2016, the percentage of U.S. Person targets is slightly higher (22.4% as compared to 19.9% in 2016). To be clear, these are not random U.S. Persons targeted at the whim of the Intelligence Community: the FISC approves applications to conduct electronic surveillance of U.S. Persons only upon a finding of probable cause that the U.S. Person targeted is a foreign power[11] or an agent of a foreign power as defined in FISA. Viewed as a whole, the statistical information regarding the exercise of “traditional ‘probable cause’ FISA authorities” furnished by the DNI in its Statistical Transparency Report does not reflect any material variation in statistical trends over the past few years, as recorded below.[12]

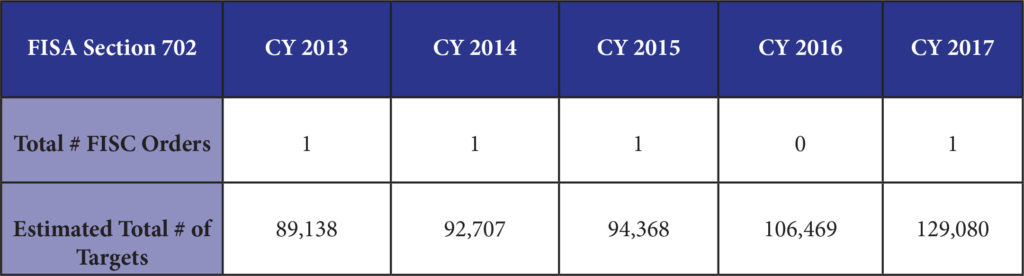

One area in which the DNI Statistical Transparency Report is more informative than either the DoJ or AOUSC reports is in its details of electronic surveillance conducted pursuant to FISA Section 702. Two areas in particular are worth mentioning. First, the overall number of Section 702 targets continues to rise, as detailed below.

The paucity of Section 702 orders is explained by the fact that: Section 702 does not require that the FISC make individualized findings regarding targets in connection with its consideration of a Section 702 certification; the FISC may issue a single order to approve more than one Section 702 certification; and, the actual number of Section 702 certifications approved by the FISC is classified for national security. All of these explanations contribute to the relatively low number of FISC Section 702 orders. The government generally seeks to have all annual Section 702 certifications handled simultaneously by the FISC and addressed by the court through the mechanism of a single order. Thus, multiple certifications can be, and often are, submitted to the FISC as a single “package” and addressed by the FISC in a single order. The government classifies the actual number of certifications and, consistent with the government’s concern regarding disclosure of the number of certifications, the DNI’s Statistical Transparency Report discloses only the number of FISC orders.

What the DNI does publicly disclose is the estimated number of Section 702 targets covered by existing FISC orders and, as reflected above, those target estimates have increased in each year that the DNI has provided those statistics. For 2017, the estimated number of targets increased by more than 20% representing the largest numerical and percentage increase in Section 702 activity since the DNI began issuing the Statistical Transparency Report after the 2013 calendar year. Clearly, the Intelligence Community, and more specifically the National Security Agency (NSA) which receives all Section 702 collection, has found Section 702 to be an increasingly significant tool in the collection of foreign intelligence information as reflected in the annual expansion of authorized Section 702 targets.

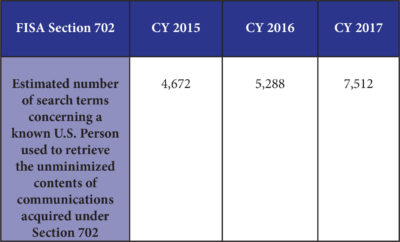

By law, targets of Section 702 electronic surveillance must be foreigners located outside the United States. The Section 702 collection program is “extremely complex, involving multiple agencies, collecting multiple types of information, for multiple purposes.”[13] One flashpoint of controversy since Section 702’s inception, however, has been the incidental collection (without any FISA “probable cause” order) of U.S. Person communications as an inevitable corollary to the acquisition of foreign target communications, and the searching (again, without any FISA “probable cause” order) of the Section 702 database containing that incidental collection (along with all other raw 702 collection) using U.S. Person identifiers. Critics condemned this “back door search” practice during the recent debate over the reauthorization of Section 702 which prompted Congress to specifically include in the renewal legislation[14] a requirement that the Attorney General and the DNI adopt “querying procedures” to insure that the querying of the Section 702 database using U.S. Person identifiers is performed “consistently with the requirements of the fourth amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”[15]

Given the high visibility the use of U.S. Person identifiers receives in connection with searches of the Section 702 database, the DNI’s disclosure that the estimated use of search terms concerning a known U.S. Person increased by more than 40% in calendar year 2017 will not be well-received by critics of the 702 Program. The historical trend in the use of “U.S. Person Query Terms” is depicted in the table that follows,[16] and it will be interesting to see the effect on that trend, if any, prompted by the adoption of the new, statutorily required “querying procedures” for use in searching the Section 702 database. With these and other changes prompted by the FISA Amendments Reauthorization Act of 2017 in the offing, next year’s Statistical Transparency Report should make for interesting reading.

With the release of the AOUSC, DoJ, and DNI reports, the annual public reporting “season” for FISA activity in 2017 has closed. Executive branch agencies involved in conducting FISA activities will continue to submit multiple additional reports and will be subjected to a plethora of other oversight regimens, but virtually all of that activity will occur outside public view. Critics will continue to debate the merits of much of what the government does under the authorities furnished by FISA, but what is beyond debate is that in no other nation on earth is a critically important foreign intelligence collection tool subjected to anything approaching the public scrutiny that FISA receives here in the United States. As, Dennis Saylor, one of the judges now serving on the FISC recently observed, “[w]e are the only country in the world, the only one of 197 sovereign nations, that interposes a court between the government and its citizens [in connection with foreign intelligence surveillance].”[17] Complementing this judicial interposition between the citizenry and the use of government surveillance, the data disclosed in the annual FISA reports helps insure that the debate on the proper role of FISA in the conduct of U.S. intelligence policy is as informed as is consistent with the national security.

[1] “Peripheral” in the sense of the more recent political manipulation of FISA by certain members of Congress. Substantively, as the Director of the National Security Agency (NSA) informed Congress, “much of what was in the intelligence community’s assessment, for example, on the Russian efforts against the U.S. election process in 2016 was informed by the knowledge we gained through 702 authority.” Transcript of the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing of May 11, 2017.

[2] The principal statutory reporting mandates are found in 50 U.S.C. § 1807 (applicable to the Attorney General) and in 50 U.S.C. § 1873 (applicable to the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts and the Director of National Intelligence), and call for the required submissions to issue in April of each year.

[3] George W. Croner, Trump’s First Year Sees a Record Number of FISA ‘Denials’: But What Do Those Numbers Mean?, FPRI E-Notes, May 4, 2018.

[4] See, e.g., Zack Whittaker, “In Trump’s first year, FISA court denied record number of surveillance orders,” Zero Day, April 25, 2018, available at https:www.zdnet.com.

[5] Zack Whittaker, “In Obama’s final year, US secret court denied record number of surveillance requests,” Zero Day, April 20, 2017, available at https:www.zdnet.com.

[6] The AOUSC reporting mandate is found at 50 U.S.C. § 1873(a), while the DoJ requirement is codified at 50 U.S.C. § 1807(a).

[7] Department of Justice annual report to Congress pursuant to 50 U.S.C. § 1807, dated April 30, 2018 (emphasis added).

[8] The FISC Rules of Procedure require that, except for emergency authorizations, the government must file an application seeking authority for its proposed activity at least 7 days prior to the date it seeks to have the application entertained by the FISC. This affords the FISC the opportunity to review the proposed application and inform the government of any concerns it has regarding its content and/or any modifications it proposes be made prior to submission of a ‘final’ application.

[9] Department of Justice annual report to Congress pursuant to 50 U.S.C. § 1807, dated April 30, 2018

[10] If you’re counting, then, the DNI “probable cause” FISA numbers reflect 1,349 final filed applications less the 2 withdrawn applications (all covering Subchapter I FISA authorities and equaling the 1,347 final filed applications reported by DoJ) plus 90 Section 704 (FISA Subchapter VI) applications (the identical number also included in the AOUSC report) for a total of 1,437 FISA orders.

[11] Under the definitions found in §1801(a) of FISA, a “foreign power” can be, among other things, “(2) a faction of a foreign nation or nations, not substantially composed of United States persons,” or “(5) a foreign-based political organization, not substantially composed of United States persons.” Because of the focus on “United States persons” in the context of these definitions, an individual might arguably be considered as, and targeted as, a “foreign power;” although, the vast number of persons constituting FISA targets are defined under the criteria used for an “agent of a foreign power” found in FISA § 1801(b).

[12] The DNI only began reporting the estimated number of U.S. Person targets for calendar year 2016 while noting that, at that time, such reporting was not statutorily required. The FISA Amendments Reauthorization Act of 2017 now requires this reporting.

[13] Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, Report on the Surveillance Program Operated Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, July 2, 2014, at 2. A full discussion and analysis of the operation of the FISA Section 702 Program can be found in my article, “The Clock is Ticking: Why Congress Needs to Renew America’s Most Important Intelligence Collection Program,” FPRI E-Notes, Sept. 29, 2017.

[14] The FISA Amendments Reauthorization Act of 2017, Pub.L. 115-118 (Jan. 19, 2018).

[15] 50 U.S.C. §1881a(f)(1)(A).

[16] In considering the figures in the table, note that the statistics reflect the number of query terms used, not the number of times any particular query term was used. For example, if the NSA uses “johndoe@XYZprovider” and “johndoe@123company” and “marydoe@XYZprovider” to query the 702 database, these are counted as three separate query events. However, if the NSA uses only “johndoe@XYZprovider,” but uses that particular search term a dozen times to search the 702 database, the statistics reflect only a single query event. See, Statistical Transparency Report, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, April 2018, pp. 14-16.

[17] A Rare Look Inside America’s Most Secretive Court, Boston College Law School Magazine, January 21, 2018.