A nation must think before it acts.

To Hack or Not To Hack?: Russia’s Decision For Election 2020

December 30, 2019

Post by Clint Watts

Debates have ensued since the last U.S. presidential election about whether Russia’s social media influence campaigns moved the electoral needle in the U.S. amidst a sea of political campaign advertising and domestic social media messaging. But what set Russia apart from other political efforts in 2016 was the employment of strategic hacking to power influence. Kremlin acquisition of kompromat and the timely release of damaging information filled newspapers, political advertisements and public discourse. Political campaigns and social media narratives attacking Hillary Clinton benefited from Putin’s strategic employment of these cyberattacks.

Hacking season for the 2020 presidential election is in full swing. Looking back to the 2016 election, Russia began its first of two hacking campaigns during the late summer and early fall of 2015, seeking out compromising information on the Clinton campaign. Political campaigns and parties, former U.S. officials, journalists and policy think tanks—all encountered phishing attempts seeking access to private communications and records that might tip the election a year later. Given that this election cycle’s optimal hacking window opened in the second half of 2019, America should expect the same tactics deployed from any country seeking to manipulate the outcome in November 2020.

Regardless of the aggressor, a foreign manipulator must hack its targets early enough to synthesize the hacked information, covertly release that information and then drive derisive narratives against its designated opponents during either the Democratic primaries or, more likely, the summer campaigns leading up to the general election. The latter scenario is a more likely one given that the field will have narrowed and the perceived impacts of compromising releases would be conceivably larger in magnitude. Multi-candidate scenarios during political primaries, similar to European elections in France and Germany, prove more difficult for the Kremlin to alter.

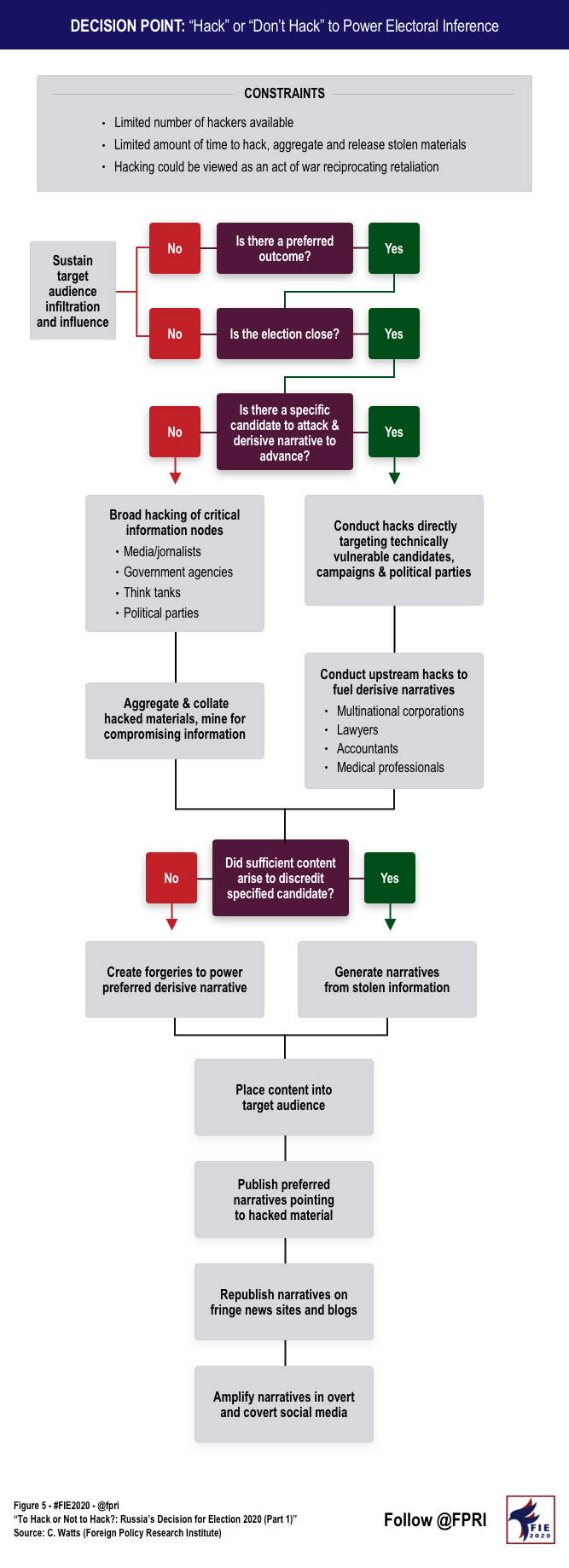

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his presidential administration face a tougher decision this time around on whether to hack targets to achieve their preferred outcome in Election 2020. Though state-sponsored hacking is easy and cheap compared to other forms of influence, the Kremlin has a finite number of hackers to employ and their cyber warriors have many other Russian strategic priorities to pursue beyond the U.S. election. In addition, compared to 2016, Russia faces greater opposition by U.S. defenders, as evidenced by U.S. Cyber Command allegedly crippling the Kremlin troll farm (Internet Research Agency) during the 2018 midterm elections and allegedly now contemplating counter information warfare against Russia. Should Putin hack U.S. targets in the 2020 cycle, Russia might very well provoke a cyberwar with America—a big “maybe,” but still a new consideration from the last election. Note that this post discusses the Kremlin’s decision to hack in support of or in detriment to specific presidential candidates and does not address Russia’s second wave of 2016 hacks targeting election infrastructure and voting processes. See this post for a timeline of Russian hacking in 2016: “So What Did We Learn? Looking Back on Four Years of Russia’s Cyber-Enabled Active Measures.”

Russia’s strategic calculus for hacking Election 2020 involves several factors (see Figure 5 below). First, does Putin have a clear preference as to whom is inaugurated in January 2021? Driving this initial determination requires an examination of what Putin seeks to achieve abroad. From the Kremlin’s perspective, foreign policy has been going great since 2016. Russia’s regained Syria, gained strength in Ukraine, conducted assassinations in Europe without consequences, dramatically expanded its influence in Africa and Latin America, undermined NATO and the EU and pushed America from global leadership while simultaneously elevating itself back to top-tier status. Undoubtedly, Putin wants to keep this momentum going, and if he can garner some sanctions relief from Washington, D.C., next term, even better. The Kremlin-sponsored content analyzed here and here last month demonstrates they’d like four more years of President Trump. If not that, the favored outcome would be a populist Democrat, rather than former Vice President Joe Biden.

A second consideration for the Kremlin: Can they tip the outcome of Election 2020 through influence operations? The Kremlin smartly engages when electoral contests appear close, whether that’s the Brexit referendum or the French and German elections. Enduring state-sponsored media content, covert social media trolling and strategic hacking from afar can only move popular support for or against a political candidate by a few percentage points. If the differential between their preferred candidate and victory appears greater than, say five percentage points, the risks and costs of hacking likely far outweigh the potential benefits of pursuing a victory via hacking. All indicators to date suggest Election 2020 will be quite close, and the Kremlin must now calculate how far they’d go to keep President Trump in office and whether hacking a Democratic opponent would make much difference.

Even with a preferred outcome and the knowledge that they might be able to tip the balance in 2020, Russia faces a conundrum they didn’t have to grapple with last cycle—who to hack. The Democratic field of 2020 candidates this time around is quite large, and the accuracy of national polling is debatable. Compared to 2016, when former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton clearly led the field, the 2020 contest has seen candidates offered up as top contenders, like Beto O’Rourke and Kamala Harris, suddenly exit the race months before anyone casts a vote. A cyberstrike in a crowded field where former Vice President Joe Biden may or may not be a reliable frontrunner—he recently polled fourth in Iowa—might achieve nothing more than a cyber counterattack.

Russia’s GRU hackers could pursue two different approaches should they decide to repeat their 2016 efforts: 1) broad hacking of critical information nodes and information brokers, or 2) surgical hacking of specific candidates with the intent to amplify specific derogatory narratives.

With broad hacking campaigns, the Kremlin penetrates the email accounts and networks of critical information nodes to harvest damaging information on candidates, political parties and institutions. Major media outlets and their journalists, poorly defended government agencies, academic think tanks and political parties offer ripe opportunities for Kremlin hackers to gather private emails and confidential files that might undermine a candidate’s chances. Once gathered, a search through the troves of correspondence and records looks for potentially damaging true information or information that might be misattributed or manipulated to drive a targeted narrative into electoral discourse.

Surgical hacking, the latter scenario, arises when the Kremlin has clearly identified a candidate they’d like to derail and a narrative they’d prefer to advance. Kremlin hackers might deliberately phish the candidate, their campaign and their political party looking for specific compromising materials. Or, if the campaign is well-defended against cyberattacks, like the U.S. candidates in 2020 rather than 2016 may be, Russia’s attackers might pursue upstream hacks to fuel available derisive narratives specific to individual candidates they’d like to degrade. Multinational corporations, law firms, banks, accountants and medical professionals all might host protected information specific to a given line of Kremlin attack—information that, if strategically exposed to the public, might sink the chances of a Putin opponent.

Examples of broad hacking to harvest compromising information might be Kremlin targeting of the Olympic committee, the German parliament (Bundestag), the persistent pursuit of George Soros and his foundations or even (allegedly) the recent disclosure of the US-UK trade negotiations. Relevant examples of a more targeted, surgical Russian approach in recent years might include efforts targeting Emmanuel Macron during the 2017 French election or Senator Marco Rubio in 2016. Note that nothing precludes the Kremlin from pursuing both hacking approaches; however, limits on resources and strengthened electoral defenses will constrain their decisions.

In both scenarios, Russian operatives transition from covert intelligence operations to overt influence manipulation, preparing to fuel specified narratives against candidates that are bolstered by laundered and released stolen information. If insufficient compromising information surfaces from cyberattacks, the Kremlin always has the option of creating forgeries, either manufacturing completely false information or manipulating stolen content, to power a preferred line of information attack.

Hacked materials and forgeries must then be placed before the target audience through either a cutout (e.g. DC Leaks in 2016) or a conduit (e.g. WikiLeaks in 2016). Once in the open, state-sponsored news outlets publish derogatory narratives against targeted candidates. These Kremlin posts rapidly fill news feeds. Fringe news sites and blogs, armed with conspiratorial content, wittingly or unwittingly amplify these attacks on candidates. Simultaneously, the Kremlin’s overt social media accounts and covert trolls designed to look like and talk like the target audience seed negative narratives into American discourse and amplify derogatory attacks against Kremlin opponents.

The Kremlin approach in 2020, unlike in 2016, is no longer a secret. Should they decide to power an attack with the aid of some hacks, the next question is:

Who would Russia hack in Election 2020?