A nation must think before it acts.

“[A] new International, not of communism this time but of vulgarity and bling…an

International with a capital I. A globalization of corruption.”

— Bernard-Henri Lévy

The Black Sea Region

Speaking at a November 2011 Valdai roundtable in Krasnogorsk, Russian President Vladimir Putin famously compared the European Union to a hamster, which, having stuffed its cheeks with food—a metaphor for new member-states—now finds itself unable to swallow.[1] Today, Mr. Putin bolsters favored political parties in a continuing effort to upset the EU’s digestion. Some of these relationships are well known: France’s Front National in December 2014 acknowledged receiving a €9.4 million loan from the Moscow-based First Czech Russian Bank.[2] Some are less so: witness Bulgaria’s radical political party Ataka (“Attack”). And some relationships require no visible patronage: Bulgaria’s Patriotic Front, which, if not discernably pro-Russia, nonetheless shares deep-rooted cultural bonds and an antipathy toward a revanchist Turkey’s geopolitical ambitions in the Balkans.

The historian Robert A. Saunders wrote recently, “Bulgaria…remains a bright spot in the old Eastern Bloc due to cultural and linguistic affinities with Russia.”[3] Those affinities are stronger than many outsiders might imagine. A 24 May 1974 United States State Department cable told “of [a] ‘rumor’ reportedly circulating” regarding “the possible entry of Bulgaria in the USSR as the sixteenth Soviet Republic and the formation of a ‘corridor’ through Romania in this connection” [sic].[4] Whether that rumor had any foundation is uncertain. It is known, however, that in 1963 and again in 1973, Bulgaria’s communist-era leaders unanimously called for the country’s eventual entry into the Soviet Union. One member of the country’s communist party Central Committee said, “not one, not two, but with five hands, if I could, I would support the proposal to as quickly join the great family of the Soviet people as possible.”[5] Another was even more effusive:

“All generations of Bulgarian Communists—our grandfathers, fathers, and we ourselves—have always cherished in their hearts the dream of transforming our country into a part of the great Soviet Union.”[6]

Cultural atavism runs deep. In late June, Bulgarian re-enactors portrayed Russian soldiers crossing the Danube to mark the 139th anniversary of Svishtov’s “liberation” from the Ottomans during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. It is one of scores of historical reenactments of the country’s “liberation” by Russia organized each year by Bulgaria’s Traditsiya (“Tradition”). Bulgarian officials again last December traveled to Moscow for the annual commemoration—initiated in 1990, ten months after Bulgaria’s first post-communist, democratically elected government took office—of “Russian soldiers who liberated Bulgaria from Turkish-Muslin oppression.” Bishop Theophylact of Dmitrov presided, saying, “Our people have always chosen to selflessly serve others for the sake of Christ’s freedom.”[7]

The Russian government supports these events through organizations such as Russkiy Mir (“Russian World”), which President Putin established in June 2007. It provides financial support to organizations outside Russia “in partnership with the Russian Orthodox Church…to promote Russian language and Russian culture.” Russkiy Mir also operates “Russian Centers” (including six in Bulgaria), offering cultural and educational programs as well as Russian-language instruction.

Fission, Fusion, and Bulgarian Party Politics

According to the Orthodox news portal Russkaya narodnaya liniya, “Orthodoxy has for centuries connected Russia and Bulgaria.”[8] It nevertheless frets in a December 2014 commentary over the question “Is Bulgaria again converting into an anti-Russian bridgehead in Europe?” The commentary quotes Fyodor Dostoevsky about the ingratitude of Slavs freed by Russian liberators:

“Of course, the moment there is any serious disaster they [Slavic peoples] will certainly turn to Russia for help. No matter how they spread hatred, gossip and slander against us in Europe, as they flirt with her and assure her of their love, they will always instinctively feel (in a moment of disaster, of course, but not before) that Europe is the natural enemy of their unity, that she always was and always will be, and that if they exist in the world it is naturally because there is a gigantic magnet, Russia, irresistibly drawing them to her … Russia’s lot for many years will be the heartbreak and travail of making peace…”[9]

If the Russian pole of Dostoevsky’s metaphorical magnet draws (some) Bulgarians toward it, it might also be said that the Turkish pole repels them. Anti-Turkish sentiment animates Bulgarian nationalism today far more than some credit. The nationalist bloc known as the Patriotic Front (Patriotichen front) is pushing for limits on the ability of Bulgarians to vote abroad—targeting ethnic Bulgarian Turks—and a so-called “burqa ban.” Four Bulgarian cities have already passed municipal ordinances prohibiting face-covering garments and imposing fines on violators of up to €2500 (about USD 1400).

“The process of party formation in Bulgaria,” wrote Michael Waller two decades ago, “has involved a mixture of fission and fusion” in which “the boundary between party and faction are at times indistinct.”[10] He identified five focal points around which “these processes of fission and fusion have taken place”—respectively, the country’s socialist née communist party, the anti-socialist/communist bloc, the Turkish minority, agrarian interests, and what he called “a political space in the middle” between the socialists née communists and the anti-socialist/communist bloc. That observation remains as valid today as it was then.

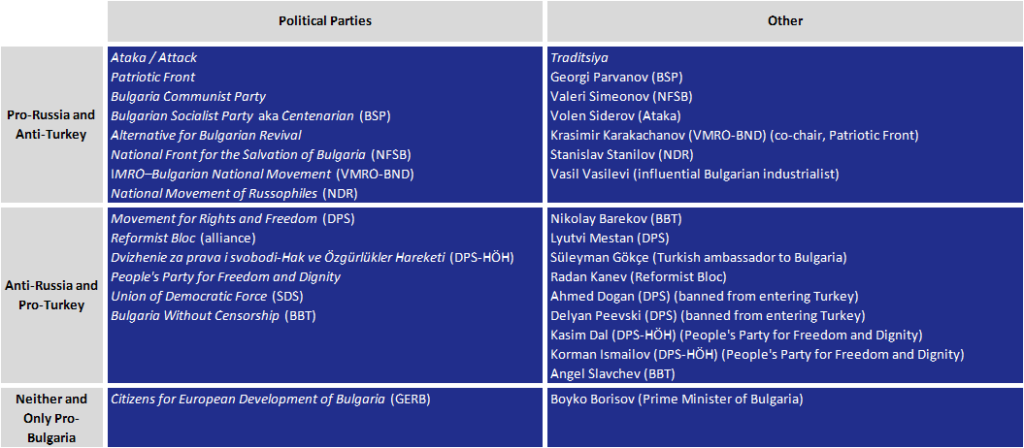

What drives the processes of fission (common) and fusion (rare, save short-lived electoral coalitions) within the atomized world of Bulgarian politics are the traditional poles of Russia and Turkey. The fractiousness of Bulgarian party politics reflects the underlying tension between a given party’s outward-looking faction—based on traditional ethnic (e.g., Bulgarian Turks) or cultural (e.g., Orthodox) bonds—and its inward-looking one.[11] Russia and Turkey exploit outward-looking factions, often with the intent of splintering Bulgarian political parties and creating, in effect, a constellation of sub-parties.[12] Each is a sub-critical cluster of like-minded voters, which sometimes form ad hoc electoral coalitions with other sub-parties. The process fosters a permanent state of political instability and frustrates efforts at political reform, effects that conspire to allow Bulgaria’s rampant political corruption to go largely unchecked.

The manipulation of Bulgarian domestic politics gained instrumental importance to Russia upon Bulgaria’s accession to full membership in NATO (2002) and the European Union (2007). It also transformed a long-standing bipolar rivalry between two external powers—Russia and Turkey—into an often-complex triangular game.

Bulgaria today remains highly dependent upon Russia, EU accession notwithstanding. This is especially true in the energy sector despite Russia abandoning the South Stream offshore pipeline project in late 2014. Gazprom supplies 90 percent of natural gas consumed by Bulgarian households. Two Russian-built operating units of the Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant supply some one-third of the nation’s electric supply. Those units are undergoing a life-extending refurbishment by the Russian state-owned Rosatom (in partnership with the United Kingdom’s EDF Energy). The Rosatom subsidiary TVEL Fuel Company supplies the units’ nuclear fuel. And Russia’s Lukoil owns the country’s only oil refinery. All told, these activities generate substantial revenue for Russian interests, one consequence of which, writes Simeon Djankov, is obvious:

“For as long as these projects have existed, they have allegedly been used for channeling bribes to certain political parties and the coterie of businessmen around them. In this manner, they have polluted Bulgaria’s political climate and have retarded its democratic development.”[13]

European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso warned in 2014 of “people in Bulgaria who are agents of Russia.”[14] He had good reason to do so. In November 2006, Vladimir Chizhov—then Russia’s ambassador to the European Union—memorably claimed, “Bulgaria is in a good position to become our special partner, a sort of a Trojan horse in the EU.”[15]

The Bulgarian MEP Nikolay Barenkov[16] earlier this year observed sardonically, “Each party, every politician and journalist in Bulgaria feels obliged to identify himself as either loving or hating Russian influence.”[17] It reveals a simple truth: both types coexist, albeit uneasily, within this EU and NATO member-state. Of the former, he said, “Putin and the Russians have many open supporters within official circles in Bulgaria. What raises concern is that [Russian] influence and political lobbying reaches into political parties, both governing and opposition, across the full political spectrum.”

Turkey itself is no stranger to Bulgarian money politics. In February 2016, published reports claimed Turkish President Recep Erdoğan’s son, Bilal, pledged to pay Bulgarian politician Lyutvi Mestan (his first name sometimes appears as “Lütfi,” in deference to the Turkish spelling) a monthly stipend of USD 1 million for a period of twenty months to fund his new political party, known by its Bulgarian acronym DOST (Demokrati za otgovornost, tolerantnost i solidarnost) or “Democrats for Responsibility, Tolerance and Solidarity.”[18] The report claimed Bilal Erdoğan also promised to produce 50,000 DOST votes from Bulgarian citizens of Turkish origin.

This led one Bulgarian news portal to declare breathlessly, “Turkey officially declares war on Bulgaria.”[19] A Turkish newspaper reported that the country’s ambassador in Sofia, Süleyman Gökçe, was to serve as the conduit for transferring funds to DOST.[20] Mr. Mestan denounced the reports as “yellow journalism” (zhŭlti izdaniya) and added that a proposed parliamentary inquiry into Russian and Turkish interference in Bulgarian domestic politics was “a grave political error.”[21]

The United States is a notable latecomer to Bulgarian power politics. In January 2016, the United States Congress instructed Director of National Intelligence James Clapper to “conduct a major review into Russian clandestine funding of European parties over the last decade” according to one published report.[22] A commentary published by the Russian government-controlled RT quickly condemned the investigation as “a farce.”[23] Another posted on the website of the Moscow-based Strategic Culture Foundation said “It’s easier to cook up dirty political schemes than act in the interests of national security.”[24]

Bulgarian Political Factions

What’s Right? What’s Left?

The presence of Russia-favoring parties on both ends of the Bulgarian political spectrum often confounds outsiders trying to understand the domestic political landscape there. In early June 2016, Bulgaria’s National Assembly (Narodno sabranie) again rejected a proposal by the second largest parliamentary party, the Bulgarian Socialist Party[25] aka “Centenarian” (Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya and Stoletnitsata, respectively). It called for removing all European Union sanctions against Russia. The measure received only 49 votes, drawing less than unanimous support from the 37 BSP members, along with the support from the National Assembly’s two smallest parties, the eleven-member center-left Alternative for Bulgarian Revival (Alternativa za balgarsko vazrazhdane) and the eleven-member ultranationalist Attack (Ataka). Therein lies the heart of the dilemma framed by Jordan Mateev: “total confusion reigns as to what is ‘Right’ and what is ‘Left’ in [Bulgarian] politics?”[26]

His comment betrays an intriguing political alignment: how is it that the successor to the former ruling communists, a small splinter party led by former BSP leader Georgi Parvanov (who was Bulgaria’s president from 2002-2012), and the rabidly nationalist Ataka coalesced around a pro-Russia parliamentary resolution? Mr. Mateev calls Ataka “an extremely far left political force.” The organization Human Rights in Ukraine (Prava Lyudyny v Ukrayini) calls it “far right” while the leftist Institute for Policy Studies’ Foreign Policy in Focus project calls it “an unlikely blend of Left and Right,” mixing “a left-wing critique of globalization with a frankly nationalist approach to minority policy.”[27] Thus, Mr. Mateev concludes, “there is not just [the horizontal variants] left and right, but also vertical variants within those categories.”[28]

However they choose to self-identify within the country’s anomalous political constellation, Bulgarians have concern about foreign meddling in their internal affairs that extends in two, not just one, geographic directions. In February 2016, parliamentary members for the Movement for Rights and Freedom (Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi or “DPS”) called for an ad hoc parliamentary committee to investigate allegations of interference in the country’s domestic politics by both Russia and Turkey.[29] Several parliamentary parties joined the DPS in passing the measure 126-19 (with 13 abstentions), with the only real opposition coming from Ataka.[30]

Prime Minister Boyko Borisov consistently eschews efforts to force Bulgaria to choose one direction or the other. He declared in January 2016, “Now, when faced with two titans who want us to say that we are pro-Russian or pro-Turkish, we say no. We are neither pro-Russian nor pro-Turkish.”[31]

Tolerance has its limits. In February, Bulgaria declared a Turkish cultural official persona non grata and gave him 72 hours to leave the country. Uğur Emiroğlu—a Turkish cultural attaché stationed in Burgas who was appointed in June 2015—was said to have engaged in activities “incompatible with his diplomatic status.” Mr. Emiroğlu, a seminary graduate who served as a mufti in Turkey, is identified in a Turkish media report as a member of “the religious affairs staff” at the Bursa consulate.[32] Another Turkish media report quoted Valeri Simeonov, a leader and founding member of the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (Natzionalen Front za Spasenie na Bulgaria or “NFSB”)—part of the Patriotic Front nationalist electoral bloc—who said on Bulgarian television that “Emiroğlu is one of the well-trained agents that Turkey has sent into Bulgaria.”[33] The Turkish news portal Odatv blamed Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or AKP), which, it said, used Bulgarian politician Lyutvi Mestan “like a puppet.” It accused the AKP of having “neo-Ottoman dreams” to import its “political Islamist” ideology into Bulgaria.[34]

Russia nevertheless sees today’s political balance in Bulgaria favoring Turkey and the country’s western allies. A 2 March 2016 Pravda commentary excoriated the Bulgarian government for inviting President Erdoğan, not President Putin, to ceremonies commemorating (as the commentary phrased it) Bulgaria’s “Day of Liberation From Turkish Oppression.”[35] It quoted Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova, who called the situation “absurd”:

“History does provide examples of a kind of ‘interference’ by Russia in Bulgaria’s internal affairs, as when Russian soldiers fought their way there by force of arms, to resist fascism and liberate their brothers from the evil. The [Bulgarian government’s] cynicism is clear in the fact that the notorious Commission was established on the eve of the 138th anniversary of Bulgaria’s liberation from the Ottoman yoke.”

The reference is to the ad hoc parliamentary committee discussed above. This is not to say Bulgarian authorities are above collaborating overtly with the Russian government when deemed necessary: witness the July 2014 arrest of Nikolay Koblyakov, founder of the Russian opposition group Russie-Liberté.[36]

Another proposed investigatory commission has potential to disrupt relations between the two countries further. Radan Kanev,[37] who leads the 23-member center-right Reformist Bloc[38] in the National Assembly, called on the Bulgarian government to request from all European Union and NATO members—“including Turkey,” he emphasized—information regarding “the Russian connections of the Bulgarian politicians Ahmed Dogan[39] and Delyan Peevski” as well as any information connecting them to Bulgartabac.

Bulgartabac is the former state-owned tobacco monopoly in which the Bulgarian Privatization and Post-Privatization Control Agency sold a majority (79.83%) stake in September 2011, its fifth attempt to do so in ten years. The sole bidder was BT Invest GmbH, an Austrian shell corporation registered in April 2011. In late June 2011, BT Invest disclosed it was owned by VTB Capital PE Investment Holding (Cyprus) Limited, whose parent corporation, JSB VTB Bank, is majority (60.0%) owned by the Russian government. A Lichtenstein corporation, Livero Establishments, agreed to acquire VTB’s stake in BT Invest at some undetermined point in the future. At the time Livero’s majority (55%) owner was the Panim Foundation, a Lichtenstein entity controlled by the aforementioned Mr. Peevski and his mother. The aforementioned Mr. Dogan reportedly received a minority (10%) stake in Livero, which he held through Inter Projects Group Ltd., an entity registered in the British Virgin Islands. In early 2014, Livero was acquired by a Dubai-registered company, TGI Middle East FZE, which itself is controlled by a second Dubai-registered company, Prest Trade Ltd.[40] Prest’s ownership cannot be ascertained from public records. In March 2014 Livero acquired BT Invest, and in June 2014 it sold half its position (equating to about a 40 percent stake) to a Lichtenstein-registered entity, Woodford Establishment,[41] which, according to one published report, is controlled Mr. Peevski.[42]

![Delyan Peevski (Source: Svobodno Slovo)[43]](https://www.fpri.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Haines-Bulgaria-080516-1-400x299.png)

Delyan Peevski (Source: Svobodno Slovo)[43]

If anything is clear from that recitation, it is why Bulgarian opposition parties have asked the country’s fellow EU and NATO member-states for assistance in untying the Gordian knot that is Bulgartabac.

Several days before the National Assembly authorized the parliamentary investigation of Messrs. Dogan and Peevski, the Turkish government banned both men from entering the country. The action was elaborated by the pro-Erdoğan newspaper Sabah (“Morning”) as responding to “pro-Russia” positions taken by them in the aftermath of “the Russian air attack against Turkey” and “the violation of Turkish airspace by Russian warplanes.” The references are to the 24 November 2015 downing of a Russian Su-24M aircraft by air-to-air missiles fired from Turkish F-16 fighter jets near the Syria–Turkey border, an incident Putin condemned as “a stab in the back” (udar v spinu).[44] Sabah called Mr. Dogan “a Soviet agent” and “an informer” for RUMNO,[45] Bulgaria’s Soviet-era military counterintelligence service.[46] The newspaper quoted an earlier characterization of Mr. Peevski by Der Spiegel as “the visible tip of an immense iceberg of corruption,” and another that called Mr. Dogan “the political mastermind behind Mr. Peevski.”[47]

Succeeding Mr. Dogan in January 2013 as head of the Movement for Rights and Freedom[48] was Lyutvi Mestan. Mr. Mestan held the post until December 2015, when he resigned to form the aforementioned party DOST.[49] Mr. Dogan denounced him in a December 2014 speech as a “Turkish fifth column inside Bulgaria.” A commentary by Metodi Andreev (a GERB[50] member of the National Assembly) wondered aloud whether Mr. Dogan’s speech, albeit unintentionally, “contained overt suggestions that Ahmen Dogan himself was Putin’s fifth column inside Bulgaria.”[51]

Mr. Dogan is in a sense responsible for yet another political party’s formation. Criticizing “feudalism, concentration of power, and totalitarian rule” within the DPS-HÖH and accusing Mr. Dogan of “using people like paper napkins,”[52] two former DPS-HÖH members—Kasim Dal, its former vice chairman who was expelled in January 2011 by the party’s central leadership council,[53] and Korman Ismailov, who resigned in January 2011 and became an independent member of parliament—in August 2012 announced the formation of a new political party, the “People’s Party for Freedom and Dignity.”[54]

Contra Turkey: Bulgarian Nationalists Coalescence (Slowly) Around a Message

“It is strange to think that Putin’s strategy of using right-wing extremist political

parties to foment disruption and then take advantage—as he did in Crimea—could

work in southern and western Europe as well.”[55]

–Mitchell A. Orenstein

Some political parties manage (unintentionally) to achieve more through failure than through success. After peaking during 2005-2013 with a resonating anti-corruption message, Ataka (literally, “Attack”) has been reduced to just a handful (11) of members in the National Assembly. While Ataka advocates “a national doctrine based on undisputed sovereignty” and “neutrality so far as military blocs”[56] are concerned, in reality the party is unabashedly pro-Russia. This sometimes leads its chief, the inveterate Holocaust denier and race baiter Volen Siderov,[57] to adopt odd positions for a party that routinely hails Orthodox Russia’s intervention to liberate Bulgaria from Ottoman rule. For example:

“It’s irrelevant whether or not anyone approves of Bashar Assad. Syria is still a sovereign country, and nobody has the right to intervene by force in its internal affairs.”[58]

![Ataka's Volen Siderov (Source: Rusofili.bg)[59]](https://www.fpri.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Haines-Bulgaria-080516-2-400x235.png)

Ataka’s Volen Siderov (Source: Rusofili.bg)[59]

In November 2012, Ataka issued a declaration forcefully denouncing the DPS-HÖH’s Mr. Dogan for, among other things, describing the Balkan War of 1912-1913 as “a war of ethnic cleansing” and “refusing for decades to recognize the Bulgarian and Armenian genocides.”

“We strongly condemned the repeated attempts by the Turkish party DPS and its leader Ahmed Dogan to revise the history of Bulgaria’s liberation and geography in order to delegitimize Bulgarian state sovereignty…We urge anyone who does not recognize Bulgaria’s wars of national liberation and who defines himself as a Bulgarian to leave, not only politics but also Bulgaria!”[60]

Ataka appealed to Bulgaria’s Constitutional Court and to the National Assembly to have the DPS-HÖH banned. “Why does no one respond to Dogan’s anti-Bulgarian speech other than Ataka and the VMRO?,” Mr. Siderov asked.

The other party to which Mr. Siderov referred—the VMRO or “Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization” (Vatreshna Makedonska Revolyutsionna Organizatsiya)—is the contemporary namesake of an anti-Ottoman national liberation movement founded in Salonika in 1893. Transitioning in 1989 from a government-tolerated cultural organization during the communist period, it renamed itself the “IMRO–Bulgarian National Movement” (VMRO–Bulgarsko Natsionalno Dvizhenie). The VMRO-BND, as it is known, first joined an anti-communist coalition called the “Union of Democratic Force” (Sayuz na demokratichnite sili ) or “SDS”.

As the VMRO-BND became increasingly nationalist and drifted rightward after 2000, it left the SDS to align with various electoral coalitions, sometimes gaining parliamentary representation. In August 2014, seeking to capitalize on Ataka’s waning support, the VMRO-BND leadership joined with the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (Natzionalen Front za Spasenie na Bulgaria) to form a national electoral alliance called the “Patriotic Front” (Patriotichen front). This effectively ended the VMRO-BND’s short-lived coalition with Bulgaria Without Censorship (Balgariya bez tsenzura, or “BBT”), which the two parties formed shortly before the May 2014 European Parliament election.[61]

The BBT was formed by Nikolay Barekov, a former news anchor at Bulgaria’s TV7[62] (owned by Delyan Peevski), several weeks before the May 2014 election. It sought to capitalize on popular disillusionment with Ataka and its leader, Mr. Siderov, whose pronouncements had become increasingly intemperate. In November 2013, for example, Mr. Siderov called for political parties to form militia-like “civil patrols…to protect the public order” as “uncontrolled refugees arrivals continue.” The patrols “won’t act in a racist manner, and will intervene only when they see an act of injustice being committed on the street,” he assured.[63] As the May elections neared, Mr. Siderov warned, “Bulgaria was melting away without a war” as “abortion, emigration, homosexuality, and permanent economic crisis destroyed the population.”[64] Choosing curiously to launch his party’s electoral campaign in Moscow, Mr. Siderov proceeded to alienate voters with strident criticisms of Sodomitskoto NATO (“Sodomite NATO”) and statements deploring “the fall of the Romanov dynasty after yet another ‘great’ revolution carried out by the self-same terrorists and queers.”[65] A few months earlier, a reportedly intoxicated Mr. Siderov verbally attacked French cultural attaché Stephanie Dumortier during a January 2014 flight from Sofia to Varna. Upon its arrival at Varna Airport, Mr. Siderov allegedly assaulted another passenger and struck a police officer.[66]

Despite the opportunity presented by Mr. Siderov’s antics, the BBT leadership was distracted by internal discord. Deputy chair Angel Slavchev loudly denounced the party’s founder, Mr. Barekov, as “a puppet of Delyan Peevski.” He called Mr. Barekov “a paper tiger” and claimed that Messrs. Barekov and Peevski “secretly speak by telephone each day using a special (SIM) card.”[67]

When it parted ways with the BBT, the VMRO-BND at the same time ruled out a future coalition with the People’s Party for Freedom and Dignity [Bulgarian: Narodna partiya „Svoboda i dostoynstvo. Turkish: Özgürlük ve Onur Halk Partisi.]. VMRO–BND deputy chair Angel Dzhamazk[68] repudiated Mr. Dal and his party, remarking caustically “If I want to talk to Erdoğan, I’ll talk to Erdoğan, not to Kasim Dal.”[69]

The Patriotic Front Emerges

The VMRO–BND’s Krasimir Karakachanov—a Patriotic Front co-chair and one of eight vice presidents of the National Assembly—was asked about Prime Minister Boyko Borissov’s recent flirtation with a Black Sea flotilla comprised of naval elements from NATO member-states Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey. He responded by first criticizing the already-dead proposal—one almost universally acknowledged to have originated with Romanian President Klaus Iohannis—saying “we were about to commit another fatal error in our relations with Russia,” and then attribuing the proposal to Turkish President Recep Erdoğan, whom he accused of bad faith:

“Erdoğan is very fickle with his partners. For example, he initiated the infamous Black Sea fleet and then one week later, abandoned the idea in the middle of Brussels.”[70]

Mr. Karakachanov said a day earlier, “Even the blind can see this Turkish-Romanian initiative is directed against Russia.”

“Why? Because Turkey is in a pre-war situation with Russia. […] Turkey downed the [Russian] aircraft then literally an hour later asked NATO to trigger Article 5, which addresses the security of a member-state that is attacked. But it was Turkey that took out a Russian plane, not Russia a Turkish one.”[71]

Krasimir Karakachanov (Source: 24 Chasa)[72]

“Bulgaria has no interest in mind games directed at a third country,” he said. “We have no place in such an initiative.” He continued:

“Then on the other hand, there’s a conflict between Romania and Russia over Moldova. It’s no secret Romania has ambitions to make Moldova part of its territory. And if Romania has some historical reasons for it, it’s also a fact that Russia has a huge Russian minority in Moldova that’s opposed to it. And don’t forget that in Moldova, there are 100,000 Bulgarians and 150,000 Bulgarian Gagauz. Right now, the pro-Romanian government in Chisinau is trying to breakup the Bulgarian administrative area [the Taraclia District[73]], a policy that would cause Bulgarians to lose the right they now have to cultural autonomy. Romania supports that [the Moldovan government’s] policy. Well, does joining this Romanian-Turkish alliance mean Bulgarians now have to take a stand against their own countrymen?”[74]

Mr. Karakachanov warned that “Erdoğan’s Turkey is a country about which we must be very careful…Ankara’s interference in our internal affairs has increased tremendously, both in terms of espionage and [Turkey’s] funding of the Chief Mufti’s office and a political party.”[75] Asked about the recent coup attempt in Turkey, Mr. Karakachanov said, “The real coup happened the next day, when Erdoğan used the situation to clear out his opponents in the leadership of the army and the judiciary.”[76]

Observing elsewhere that “the world has returned to a situation of cold war [between NATO and Russia] over the last ten to twelve years,”[77] Mr. Karakachanov said Bulgaria’s president “should be a patriot, not a Euro-Atlantic parrot.”

“We have a president who is a Euro-Atlanticist…Naturally, [the country’s president] should be a patriot, a politician who as head of state can say ‘no’ when it is not in the interest of Bulgaria, not just read ancient scripts [literally, “papyrus”] containing clichés about Euro-Atlantic sovereignty. Where was Euro-Atlantic sovereignty when several large and wealthy European countries pressed us for economic reasons to close units 3 and 4 of Kozloduy [Nuclear Power Plant]? Did they show solidarity and understanding with respect to how cheap Bulgarian electricity from Kozloduy helps poor people in Bulgaria and our economy?”[78]

One must acknowledge his use of a politically loaded Russian meme—”Euro-Atlanticist” (yevroatlantistskimi)—whether he intended (likely) the term to be heard in that context or not (unlikely). The United States, writes Eurasianism theorist Aleksandr Dugin, employs “a strategy of the anaconda”[79] as part of its Euro-Atlanticist “Mackinder-esque way to world domination”:

“Thus do we see Mackinder’s way to world domination: ‘Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; Who rules the World Island commands the World.’ Nothing has changed today. A ‘cordon sanitaire’ of nationalist anti-Russian states in Eastern Europe, only vaguely aware of how they define continental Europe’s identity, is put into place to serve the same purpose [as in Mackinder’s theorem]. These countries have been integrated into NATO, and some will host elements of a United States missile defense system that is clearly directed at Russia. Naturally, these countries assume a Euro-Atlanticist posture toward Russia, not just because their governments are anti-Russian, but also because they are not independent and are used instrumentally by the United States.”[80]

Switching to Nicholas Spykman’s term Rimland—a crescent that includes Bulgaria, positioned as it is on NATO’s eastern frontier—Dugin writes “Rimlands are indispensable for Russia if it is ever to become a genuinely sovereign, continental geopolitical power.”[81]

Returning to domestic politics, Mr. Karakachanov said he hopes to “consolidate the efforts of all patriotic parties and organizations in Bulgaria,”[82] an effort that may extend to bringing Ataka into the Patriotic Front.[83]

“My first goal is to try and repair the bridge that broke down between our colleagues from Ataka and the NFSB over the past several years. We have a great relationship with the NFSB and good relations with Ataka. So I want to rebuild the bridge between them, so that we can be stronger. I’ve always thought patriotism cannot be the monopoly of just one or two parties…”[84]

His Patriotic Front co-spokesperson, Valeri Simeonov,[85] set a precondition, however: Ataka “must abandon its Russophilia,” referring to its close relationship with the National Movement of Russophiles (Natsionalno dvizhenie rusofili “NDR”). The NDR’s priorities were spelled out by its deputy chair, Stanislav Stanilov, as “resisting anti-Russian sanctions, the struggle against the expansion of NATO’s presence in the country, and categorical opposition to any suggestion that Bulgaria participate in NATO’s anti-Russian potential aggression.”[86] Ataka and the NDR have much in common — for example, their opposition to Montenegro’s NATO accession. The NDR quotes Mr. Siderov’s declaration approvingly that “the chant can be heard at rallies in Bulgaria and Montenegro: NATO is a terrorist and fascist.”[87] So, too, Mr. Siderov’s denunciation of Bulgaria’s planned purchase of “old F-16 fighters” instead of MIG-29 aircraft:

“Don’t get me wrong. Ataka has said for years that Bulgaria should have a strong air force, rather than the absurdity of turning to Turkey to protect our airspace…But when you talk about your Euro-Atlantic NATO allies, let me hasten to remind you the United States literally gave Egypt eight F-16 fighters. So why don’t they give them to you [the Bulgarian government]? You’re their allies, right?”[88]

Mr. Karakachanov said, “The VMRO’s objective is to try and unite all patriotic organizations, the VMRO and the NFSB[89] and Ataka…with the idea of forming a single patriotic slate”[90] in time for the country’s October 2016 presidential election. He said the next President:

“Needs to be a Bulgarian patriot, a man with backbone, who will defend Bulgaria’s interests at home against economic oligarchy and various economic interests. […] And in foreign policy…someone who will take a balanced approach to relations in a very risky region. ‘Bulgarian interests above all else.’ That should be the next Bulgarian President’s motto and his political practice…”[91]

“In Bulgaria there are two ways out of the crisis:

Terminal 1 and Terminal 2 at the airport”[92]

One of the clearest expressions of party alignment with Russia or Turkey (or neither) came in the aftermath of the 24 November 2015 downing of a Russian aircraft in Turkish airspace near the Syria-Turkey border. Speaking for the DPS-HÖH, Mr. Mestan defended Turkey’s actions and laid the blame on Russia. GERD’s Mr. Tsvetanov urged neutrality. The BSP’s Mr. Stoilov called for an international investigation of the incident, while several BSP members walked out during Mr. Mestan’s speech. And Ataka’s Mr. Siderov called on the National Assembly to draft a declaration “condemning the military aggression of the Republic of Turkey toward the Russian Federation.” He called Turkey’s action “a barbaric military provocation,” and said that by downing the Russian aircraft, Turkey “declared its support for [Islamic State].”[93]

What is the reaction of ordinary Bulgarians to their country’s constant political turmoil and division? Emigration, as the news portal 24 Chasa (“24 Hours”) found recently. “Three and a half million Bulgarians live outside the country,”[94] a shocking number in a country whose population is around 7 million.

How does Russia view the situation? One answer lies in the title of an October 2014 report by the Moscow-based think tank the Center for Political Analysis: “How Bulgaria’s oligarchic elite have betrayed Russia.”[95] Maxim Zharov put it this way: “Bulgaria is controlled by oligarchic clans, which are more focused on the EU in order to obtain loans and other types of assistance.” “Bulgaria,” he explained, “is different than Serbia, where many social movements cooperate with Russia and pro-Russian political parties.” That being said, “it is impossible to say that Bulgarians are less like Russians than the Serbs. It’s just that the Bulgarian political system is configured in such a way that the interests of citizens sympathetic to Russia simply do not count.” Another person quoted in the report, Boris Shmelev, said that Bulgaria, while it owes far more to Russia and the Soviet Union than Serbia, has (unlike Serbia) unequivocally sided with the West.

“At one time, some Bulgarian politicians argued: Bulgaria cannot be an ally of Russia, but should not be the enemy of Russia. Among the current Bulgarian government and the Bulgarian political elite, this principle, unfortunately, is not observed.”

While Russia may prefer the unalloyed fealty of Ataka, it is nonetheless true that the Patriotic Front observes the principle articulated by Mr. Shmelev—if not Russia’s ally, then neither is it Russia’s enemy. Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov may indeed be European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s “golden boy”—Mr. Juncker’s actual term for him[96]—but right now, Prime Minister Borissov depends upon the Patriotic Front to maintain his governing coalition intact.

One suspects Mr. Juncker would find some other term to describe the Patriotic Front leadership, should the party prevail in October’s election. In late July, the Patriotic Front proposed to ban foreign citizens from conducting religious services or ceremonies in Bulgaria, and to prohibit anyone from doing so in a language other than Bulgarian. The objective, said Mr. Karakachanov, is clear: to end Turkish meddling in Bulgarian affairs through the conduit of Muslim religious institutions. He referred to a bilateral agreement under which the Turkey’s constitutionally established Presidency of Religious Affairs, the Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı, funds Bulgaria’s Muslim religious schools. “Why,” he asked, “doesn’t anyone in the media ask why Bulgaria’s Chief Mufti is under the hidden influence of the Diyanet?”[97] The measure would require religious organizations to declare any account held at a non-Bulgarian bank or financial institution; prohibit them from accepting donations from non-Bulgarian citizens or institutions; and prohibit them from collaborating with organizations “with foreign participation.”[98] Valeri Simeonov, who is Mr. Karakachanov’s Patriotic Front co-chair, said “90 Turkish nationals direct [Bulgaria’s] Grand Mufti’s office…In other words, Islam in Bulgaria isn’t a religion at the moment but rather a way for the Turkish state to intervene in Bulgaria’s internal affairs. Nothing else.”[99]

All this is made even more interesting by the unexpected advancement of Bulgaria’s assumption of the European Union presidency, which likely will jump forward by six months to June 2018 as a result of the United Kingdom’s Brexit decision.

Right now, the presence of a determinedly anti-Turkey Bulgaria inside NATO and the EU may suffice for Russia’s purpose of exploiting fissures within those organizations. Claiming “the large European countries would betray Bulgaria in favor of Turkey if it was to their advantage,” influential Bulgarian industrialist Vasil Vasilevi called in late July for a Balkan “union to deter this Turkish threat.” It would include Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Macedonia, “and theoretically, Romania can join, too.”[100]

“I don’t think we can count on either NATO or the EU, and I’m convinced neither organization would lift a finger to defend Bulgaria’s independence, sovereignty, or territorial integrity against an attack or even a mass invasion by hundreds of thousands of so-called ‘refugees’ or ‘migrants’ from Turkey, which in practice would be like an irregular military force and would achieve the same things that a military operation would achieve.”

Nor, he added, should Bulgaria “count on Russia to help us, because over many governments, Bulgaria has done everything possible to cause Russia to become disgusted with it.”

No one should doubt Bulgarian nationalists’ patriotism or the unease with which many ordinary Bulgarians observe events unfolding in neighboring Turkey. While anti-Turkish sentiment has always coexisted uneasily with the presence of a sizeable ethnic minority, its more rabid variants (like Ataka) have so far remained on the political periphery. Should political change in Bulgaria—and Mr. Erdoğan’s continued movement toward authoritarian rule and Ottoman revanchism—intersect, the effect may indeed choke Mr. Putin’s metaphorical European hamster.

The title is from a November 2014 essay by the Bulgarian investigative journalist Assen Yordanov, who cofounded the news portal Bivol. He wrote of “the suffocating symbiosis between the formerly ruling Communist cliques in Bulgaria and Russia.” See: Yordanov (2014). “Im Würgegriff der Vergangenheit.” Ostpol [published online in German 11 November 2014]. https://ostpol.de/beitrag/4138-im_wuergegriff_der_vergangenheit. Last accessed 17 July 2016. The quotation is from Bernard-Henri Lévy (2016). “The world according to Trump.” Kyev Post [published online 15 March 2016]. https://www.kyivpost.com/article/opinion/op-ed/bernard-henri-levy-the-world-according-to-trump-409979.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

The translation of all source material is by the author unless otherwise noted.

[1] “Vladimir Putin dal ponyat’ Zapadu, chto “tandem” rano spisyvat’ so schetov.” RG.ru [published online in Russian 14 November 2011]. https://rg.u/2011/11/13/valday-site.html. Last accessed 14 July 2016.

[2] “We should beware Russia’s links with Europe’s right.” The Guardian [published online 8 December 2014]. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/dec/08/russia-europe-right-putin-front-national-eu. Last accessed 15 July 2016.

The First Czech-Russian Bank (FCRB) was founded in the Czech Republic in 1996 “to serve foreign trade and investment projects between Russia and the Czech Republic.” On 1 July 2016, the Central Bank of Russia revoked the FCRB’s license. See: https://www.cbr.ru/eng/press/pr.aspx?file=01072016_130402eng2016-07-01T12_57_03.htm. Last accessed 15 July 2016. The FCRB was founded in 1996 with the assistance of another bank, Investicini a Postovni Banka (IPB). The IPB was seized by the Česká národní banka (the Czech central bank) after the IPB’s near collapse in 2000. By one assessment, “IPB was a legendary nexus of asset stripping and money laundering, often accused of illegally funding both the Civic Democratic Party and Social Democrats, the two largest and most influential parties in the country comprising mostly of former communist hacks…The BIS and UZSI are concerned that the European-Russian Bank and the First Czech-Russian Bank could have ties to Russian intelligence, or organized crime elements.” See: “From Tanks to Spies to Banks – the European-Russian Bank.” The Jamestown Foundation Blog on Russia and Eurasia [published online 12 September 2009]. https://jamestownfoundation.blogspot.com/2009/09/from-tanks-to-spies-to-banks-european.html. Last accessed 15 July 2016.

According to published reports, the FCRB’s sole shareholder is Roman Yakubovich Popov, a Russian businessman and financier. Mr. Popov was chief financial officer of OJSC Stroitransgaz in 2005 when that company entered into a five-year agreement with the Czech government to recapitalize the FCRB, with the intention of selling it afterward. Mr. Popov later acquired the Czech government’s stake in FCRB, reportedly using funds raised by selling his Stroitransgaz shares. Stroitransgaz is a privately held Russian engineering and construction and key supplier of oil pipeline equipment to Gazprom. It is controlled by the Volga Group, which is a holding company controlled by Gennady Timchenko. A Russian oligarch and close ally of Mr. Putin, Mr. Timchenko is the subject of sanctions by the United States Treasury (https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0133.aspx) and the European Union.

[3] Robert A. Saunders (2014). “The Geopolitics of Russophonia: The Problems and Prospects of Post Spviet ‘Global Russian’.” Globality Studies Journal. 40 (15 July 2014). https://gsj.stonybrook.edu/article/the-geopolitics-of-russophonia-the-problems-and-prospects-of-post-soviet-global-russian/. Last accessed 22 July 2016.

[4] United States State Department (1974). Cable dated 24 May 1974 classified SECRET from Romania Bucharest to Bulgaria Sofia|Department of State and Russia Moscow|Secretary of State titled “Rumor Concerning Alleged Plan to Amalgamate Bulgaria with USSR.” https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/1974BUCHAR02231_b.html. Last accessed 23 July 2016. The rumor’s source is described as a “trustworthy NATO-country embassy officer” who had a claimed “80-percent reliability rating.”

[5] The speaker was Radenko Vidin, who was a member of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party. Quoted in Zhelyu Zhelev (2009). V bol’shoĭ politike. (Sofiya) 12-15.

[6] The speaker was Luchezar Avramov, a Central Committee candidate-member. Ibid.

[7] “Nash narod vsegda predpochital zhertvenno sluzhit’ drugim radi svobody Khristovoy.” Russkaya narodnaya liniya [published online in Russian 12 December 2016]. https://ruskline.ru/news_rl/2015/12/12/sostoyalas_panihida_v_pamyat_pobedy_russkih_vojsk_nad_turkami_vo_vremya_russkotureckoj_vojny_187778_godov/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[8] “Bolgariya snova prevrashchayetsya v antirossiyskiy platsdarm Yevropy?” Russkaya narodnaya liniya [published online in Russian 14 February 2014]. https://ruskline.ru/news_rl/2014/12/02/bolgariya_snova_prevrawaetsya_v_antirossijskij_placdarm_evropy/&?commsort=votes. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[9] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1997). A Writer’s Diary. Volume 2: 1877-1881. (Evanston: Northwestern University Press)1201-1202.

[10] Michael Waller (1995). “Making and Breaking: Factions in the Process of Party Formation in Bulgaria.” In Richard Gillespie, Lourdes Lopez Nieto & Michael Waller, eds. Factional Politics and Democratization. (Abingdon, UK: Routledge & Co. Ltd.) 152-153. Also published as Waller (1995). “Making and breaking: Factions in the process of party formation in Bulgaria.” Democratization. 2:1 (Special Issue: Factional Politics and Democratization) 152-167.

[11] The terms “inward-looking” and “outward-looking” are borrowed from Antoine Roger’s 2002 monograph. See: Roger (2002). “Economic Development and Positioning of Ethnic Political Parties: Comparing Post-Communist Bulgaria and Romania.” Southeast European Politics. III:1 (June 2002) 20-42. https://www.seep.ceu.hu/archives/issue31/roger.pdf. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[12] Political scientists distinguish between two types of sub-parties, factions and tendencies. A faction is distinguished by “cohesion and discipline” [Richard Rose (1964) Politics in England. (Boston: Little, Brown) 36] and by the ability “to act collectively” [Raphael Zariski (1960). “Party Factions and Comparative Politics: Some Preliminary Observations.” Midwest Journal of Political Science. 4:1, 33]. A faction is an organization of political competition. It is the shared identity, purpose or issue, Raphael Zariski argued, that allows a faction to operate as a bloc.

[13] Simeon Djankov (2015). “Bulgaria: Slayer of Russian Energy Projects.” Published online by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, 21 January 2015. https://piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/bulgaria-slayer-russian-energy-projects. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[14] “Russia’s South Stream pipeline in deep freeze as EU tightens sanctions noose.” The Telegraph [published online 7 April 2014]. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/energy/oilandgas/10750840/Russias-South-Stream-pipeline-in-deep-freeze-as-EU-tightens-sanctions-noose.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[15] Ambassador Vladimir Chizhov has served since September 2005 as Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the European Union. He made the comment during a 10 November 2006 interview with Kapital, a Bulgarian language weekly business newspaper. See: “Poslanikŭt na Rusiya v Evropeĭskiya sŭyuz Vladimir Chizhov: Vie ste nashiyat troyanski kon v ES v dobriya smisŭl.” Kapital [published online in Bulgarian 10 November 2006]. https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2006/11/10/293214_vladimir_chijov_vie_ste_nashiiat_troianski_kon_v_es_v/php?storyid=293214. Last accessed 15 June 2016.

[16] He is the leader of the political party Balgariya bez tsenzura (“Bulgaria Without Censorship”), which he founded in January 2014. See the discussion later in this essay.

[17] “Bulgaria: Doklad starta – vliyanieto na Rusiya v Bŭlgariya.” EU Reporter [published online in Bulgarian 25 February 2016]. https://bg.eureporter.co/frontpage/2016/02/25/bulgaria-report-launch-russias-influence-in-bulgaria/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[18] “Bulgaristan krizine de ‘Bilal’ adı karıştı.” BirGün [published online in Turkish 24 February 2016]. https://www.birgun.net/haber-detay/bulgaristan-krizine-de-bilal-adi-karisti-104630.html. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[19] “Voĭnata na Turtsiya Sreshtu Bŭlgariya Obyavena Ofitsialno–Mestan Sŭzdava DOST.” Bradva [published online in Bulgarian 28 February 2016]. https://bradva.bg/bg/article/article-74487#.V414T1c4muV. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[20] BirGün (24 February 2016), op cit.

[21] “Lyutvi Mestan: Ne poznavam sina na Erdogan, DOST nyama da se finansira ot Turtsiya.” 24 Chasa [published online in Bulgarian 28 February 2016]. https://www.24chasa.bg/Article/5331468. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[22] “Russia accused of clandestine funding of European parties as US conducts major review of Vladimir Putin’s strategy.” The Telegraph [published online 16 January 2016]. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/12103602/America-to-investigate-Russian-meddling-in-EU.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[23] “US investigation into ‘Russian meddling’ in the EU will be a farce.” RT [published online in English 19 January 2016]. https://www.rt.com/op-edge/329433-investigation-russia-eu-meddling/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[24] Dmitriy Sedov (2016). “NATO: Parkinson’s Law Used to Restore Order.” Strategic Culture Foundation [published online 26 January 2016]. https://www.strategic-culture.org/pview/2016/01/26/nato-parkinsons-law-used-restore-order.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[25] The self-declared socialist Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya or “BSP” is the successor to the communist Balgarska Komunisticheska Partiya that ruled the People’s Republic of Bulgaria from 1946 until 1989.

[26] “Koĭ e lyav i koĭ desen v Bŭlgariya?” Kapital [published online in Bulgarian 14 May 2007]. https://www.capital.bg/blogove/arhiv/2007/05/14/339581_koi_e_liav_i_koi_desen_v_bulgariia/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[27] https://fpif.org/bulgarias-ataka-party-an-unlikely-blend-of-left-and-right-2/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Deputatite vse pak shte prouchvat dali Rusiya i Turtsiya se mesyat na Bŭlgariya.” Dnevnik [published online in Bulgarian 19 February 2016]. https://www.dnevnik.bg/bulgaria/2016/02/19/2708009_deputatite_vse_pak_shte_prouchvat_dali_rusiia_i/. Last accessed 15 July 2016.

[30] Other parliamentary parties signing the petition were the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (Graždani za evropejsko razvitie na Bǎlgarija or “GERB”), the largest parliamentary bloc; the Bulgarian Socialist Party (Bǎlgarska sotsialisticheska partiya); the Patriotic Front (Patriotichen front) coalition formed by the IMRO-Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO-Bǎlgarsko natsionalno dvizhenie) and the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (Natsionalen front za spasenie na Bǎlgariya); and the Bulgarian Democratic Center (Bǎlgarski demokratichen tsentar). Some members of the Bulgarian Socialist Party opposed the inclusion of Russia in the resolution.

[31] “Borisov garantira proval na nov kabinet sled predsrochni izbori. Ne sme proruski ili proturski, a evroatlantitsi.” Mediapool.bg [published online in Bulgarian 19 January 2016]. https://www.mediapool.bg/borisov-garantira-proval-na-nov-kabinet-sled-predsrochni-izbori-news244396.html. Last accessed 17 January 2016.

[32] “Kavga etmediğimiz bir Bulgaristan kalmıştı Türker Ertürk yazdı: Kavga etmediğimiz bir Bulgaristan kalmıştı.” Odatv [published online in Turkish 23 February 2016]. https://odatv.com/kavga-etmedigimiz-bir-bulgaristan-kalmisti-2302161200.html. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[33] “Bulgaristan’la Ataşe Krizi.” Gazeteport [published online in Turkish 22 February 2016]. https://gazeteport.com/2016/bulgaristanla-atese-krizi-23521/. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[34] odatv (23 February 2016), op cit.

[35] “Bolgariya otprazdnuyet osvobozhdeniye ot osmanov s Erdoganom i bez Rossii.” Pravda [published online in Russian 2 March 2016]. https://www.pravda.ru/news/world/02-03-2016/1293995-bulgaria-0/. Last accessed 19 July 2016. Bulgaria celebrates ‘National Liberation Day” to mark the reestablishment of the Bulgarian state after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano on 3 March 1878.

[36] “Bulgaria arrested a prominent opponent of Putin—Nikolay Koblyakov.” Bivol.bg [published online 30 July 2014]. https://bivol.bg/en/kobliakov-english.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[37] Mr. Kanev is the leader of the political party Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (Demokrati za silna Bălgarija or DSB).

[38] The Reformist Block is a parliamentary coalition of Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (Demokrati za silna Bălgarija or DSB), Bulgaria for Citizens Movement (Dvizhenie „Bulgariya na grazhdanite“), Union of Democratic Forces (Sayuz na demokratichnite sili), People’s Party Freedom and Dignity (Narodna partiya „Svoboda i dostoynstvo“), and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (Bǎlgarski Zemedelski Naroden Sǎjuz).

[39] Mr. Dogan chaired Bulgaria’s Movement for Rights and Freedom party from 1990 through January 2013.

[40] https://www.ffbh.bg/en/news/bulgartabac-holding-with-new-majority-owner-neutral. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[41] https://seenews.com/news/two-liechtenstein-cos-jointly-hold-majority-stake-in-bulgarias-bulgartabac-parent-media-428121. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[42] This is a highly condensed version of the detailed roadmap set out in a series of investigative reports published by the Bulgarian investigative journalism portal Bivol. See: “Bulgartabac I.” Bivol.bg [published online 1 August 2015]. https://bivol.bg/en/bulgartabac-mafia-part-1.html. Last accessed 16 @016. See also: “Bulgartabac II.” Bivol.bg [published online 12 August 2015]. https://bivol.bg/en/bulgartabac-mafia-part-1.html. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[43] https://www.svobodnoslovo.eu/2016/01/15/welcome-to-шишиland/. Last accessed 24 July 2016.

[44] “Udar v spinu: zayavleniya Vladimira Putina ob intsidente s Su-2.” RIA Novosti [published online in Russian 24 November 2015]. https://ria.ru/world/20151124/1327592353.html. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[45] RUMNO is the acronym of Razuznavatelno Uptavlenie na Ministerstvoto na Narodnata Otbrana.

[46] “Rus yanlısı Doğan’a ülkeye giriş yasak.” Sabah [published online in Turkish 11 Feb ruary 2016]. https://www.sabah.com.tr/gundem/2016/02/11/rus-yanlisi-dogana-ulkeye-giris-yasak. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[47] “Bulgarischer Politiker Peewski: Eisberg der Korruption.” Der Spiegel [published online in German 31 January 2016]. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/bulgarien-dps-abgeordneter-deljan-peevski-sorgt-fuer-kontroverse-a-1074203.html. Last accessed 16 July 2016. The description of Mr. Peevski reads in the original German “Sichtbarer Teil des großen Eisbergs der Korruption”

[48] Consistent with its focus on the interests of Bulgaria’s ethnic Turks, the party goes by the Bulgarian name Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi (DPS) as well as the Turkish one Hak ve Özgürlükler Hareketi (HÖH). The author has elected to use the combined Bulgarian-Turkish acronym “DPS-HÖH”.

[49] DOST is an acronym for Demokrati za otgovornost tolerantnost i solidarnost (“Democrats for Responsibility, Tolerance and Solidarity”) and an intentional double entendre that also means “friend” in Turkish. In July 2016, a Bulgarian court refused to register DOST as a political party citing Bulgaria’s constitutional ban (Article 11/4) on the formation of parties “on an ethnic, racial, or religious basis.” Bulgarian law also prohibits the use of any language other than Bulgarian in public events including election campaigning. See: “DOST shte obzhalva sŭdebnoto reshenie za otkaz ot registratsiya na formatsiyata.” Bnr.bg [published online in Bulgarian 8 July 2016]. https://bnr.bg/post/100713272. Lasst accessed 19 July 2016.

[50] An acronym for Graždani za evropejsko razvitie na Bǎlgarija (“Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria”). GERB is a center-right political party with 84 members in the 240-seat National Assembly. It is led by Boyko Borisov, Bulgaria’s Prime Minister since 2014.

[51] “Metodi Andreev: Dogan e “petata kolona” na Putin v Bŭlgariya.” Mediapool.bg [published online in Bulgarian 23 December 2015]. https://www.mediapool.bg/metodi-andreev-dogan-e-petata-kolona-na-putin-v-bulgaria-news243455.html. Last accessed 16 July 2016.

[52] “Kasim Dal i Korman Ismailov pravyat nova partiya.” Vesti [published online in Bulgarian 25 September 2012]. https://www.vesti.bg/bulgaria/politika/kasim-dal-i-k.-ismailov-praviat-nova-partiia-5155991. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[53] Mr. Dal’s falling out with DPS party leader Ahmed Dogan was on public display during Turkish President Recep Erdoğan’s visit to Sofia in October 2010, during which Mr. Erdoğan held an unscheduled meeting with Mr. Dal. While Mr. Dal at the time chaired a parliamentary group promoting Bulgarian-Turkish “friendship,” his public estrangement from the DPS leadership led observers to conclude that Mr. Erdoğan was signaling that Mr. Dogan had lost Turkey’s support. A commentary in the respected Bulgarian business weekly Kapital assessed “One possible explanation is that [Mr. Erdoğan] is distancing himself from Dogan because of corruption scandals…” See: “Nashite mili sŭsedi Turskiyat premier doĭde vnezapno, postavi vŭprosite si i si trŭgna..” Kapital [published online in Bulgarian 8 October 2010]. https://www.capital.bg/politika_i_ikonomika/bulgaria/2010/10/08/973669_nashite_mili_susedi/. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[54] The party’s name in Bulgarian is Narodna partiya „Svoboda i dostoynstvo“ and in Turkish is Özgürlük ve Onur Halk Partisi. It competed in the October 2014 European Parliament elections as part of the five-party Reform Bloc (Reformatorski blok). Its sole successful candidate was Svetoslav Malinov of Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (Demokrati za silna Bălgarija).

[55] Mitchell A. Orenstein (2014). “Putin’s Western Allies: Why Europe’s Far Right Is on the Kremlin’s Side.” Foreign Affairs [published online 25 March 2014]. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-03-25/putins-western-allies. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[56] https://www.ataka.bg/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=14&Itemid. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[57] Some among Mr. Siderov’s many detractors have called for his (along with his party’s) banishment from public life, citing, among other things, the Bulgarian criminal code’s prohibition against racial and ethnic incitement and advocating discrimination (Article 162 of the Criminal Code) and religious hatred (Article 164 of the Penal Code).

[58] “E Dŭrzhavniyat Suverenitet.” Kultura [published online in Bulgarian 9 September 2013]. https://kultura.bg/web/безусловен-ли-е-държавният-суверенит/. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[59] https://rusofili.bg/атака-против-закупуването-стари-из/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[60] “ATAKA iska Konstitutsionniyat sŭd da zabrani DPS Siderov prizova dŭrzhavnite institutsii da zakleĭmyat opita na Dogan da otreche suvereniteta i teritorialnata tsyalost na Bŭlgariya.” Vesnikataka.com [published online in Bulgarian 13 November 2012]. https://www.vestnikataka.bg/2012/11/атака-иска-конституционният-съд-да-за/. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[61] The Balgariya bez tsenzura (“BBT”) was formed several weeks before the May 2014 European Parliament elections in an effort to capitalize on popular disillusionment with Ataka and its leader, Volen Siderov.

[62] TV7 was owned by New Bulgarian Media Group (which is owned by the aforementioned Mr. Peevski’s mother, Irena Krasteva), which acquired it with financing from the now-insolvent Corporate Commercial Bank (CCB), the same method that New Bulgarian Media Group used to acquire a number of print publications. See: https://sofiaglobe.com/2016/05/13/bulgarian-court-declares-tv7-broadcaster-insolvent/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[63] “Siderov: Grazhdanskite patruli shte pomagat za opazvane na reda.” Vesti [published online in Bulgarian 23 November 2013]. https://www.vesti.bg/bulgaria/siderov-grazhdanskite-patruli-shte-pomagat-za-reda-5999168. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[64] “Bŭlgariya se topi bez voĭna.” Ataka [published online in Bulgarian 14 March 2014]. https://www.vestnikataka.bg/2014/03/българия-се-топи-без-война-6-милиона-аб/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[65] “Ima samo edna natsionalna doktrina – Volen Siderov. Vŭzrazhdaneto na Bŭlgariya zavisi ot vsichki nas.” Ataka [published online in Bulgarian 17 April 2014]. https://www.vestnikataka.bg/2014/04/има-само-една-национална-доктрина-вол/. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[66] “France Demands Apology from Bulgarian Nationalist.” Balkan Insight [published online 8 January 2014]. https://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/france-demands-apology-from-bulgarian-nationalist. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[67] “Angel Slavchev: Nikolaĭ Barekov e marionetka na Delyan Peevski.” bTV Novinite [published online in Bulgarian 24 November 2014]. https://btvnovinite.bg/article/bulgaria/politika/angel-slavchev-nikolai-barekov-e-marionetka-na-delyan-peevski.html. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[68] He at the time was part of the “Bulgaria without Censorship” (Balgariya bez tsenzura) electoral coalition and is now part of the Patriotichen front (“Patriotic Front”). In late 2013, the Sofia District Prosecutor started trial proceedings against Mr. Dzhambazki for alleged hate speech. In May 2016, the British Conservative MEP Syed Salah Kamall wrote an open letter to fellow members of the European Parliament Anti-Racism and Diversity Intergroup (of which he is Co-President) urging “immediate action” with regard to “racist, xenophobic and homophobic speech by Angel Dzhambazki MEP.” According to Mr. Kamall, “Mr Dzhambazki has in the past few weeks openly called for a civil war against Roma in Bulgaria in an article authored by him as well as engaged in hate speech online against Roma people, Muslims and LGBTI people.” See: https://www.ardi-ep.eu/2016/05/13/letter-to-syed-kamall-regarding-hate-speech-by-mep-angel-dzhambazki-10052016/. Last accessed 18 July 2016. An illustrated exposé published on a Bulgarian language news portal described him as “a skinhead with far-right views.” See: “Liderŭt na VMRO Dzhambazki – skinar s kraĭno desni vŭzgledi.” Flagman.bg [published online in Bulgarian 29 April 2011]. https://www.flagman.bg/article/25423. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[69] “Patriotichniyat front ne iska koalitsiya s Reformatorite.” OFFNews [published online in Bulgarian 5 October 2014]. https://offnews.bg/news/n_1/n_398838.html. Last accessed 18 July 2016.

[70] “Krasimir Karakachanov: Istinskiyat prevrat v Turtsiya se sluchi na drugiya den.” 24 Chasa [published online in Bulgarian 19 July 2016]. https://www.24chasa.bg/mnenia/article/5655149. Last accessed 21 July 2016. The interview also appeared on the website of Mr. Karakachanov’s political party, the VMRO–Bulgarsko Natsionalno Dvizhenie (“VMRO-BND”). See: https://www.vmro.bg/красимир-каракачанов-истинският-преврат-в-турция-се-случи-на-другия-ден/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[71] ” Karakachanov: Plevneliev i Nenchev iskat da ni izpravyat sreshtu Rusiya s rumŭnsko-turski sŭyuz.” VMRO.bg [published online in Bulgarian 20 July 2016]. https://www.vmro.bg/каракачанов-плевнелиев-и-ненчев-искат-да-ни-изправят-срещу-русия-с-румънско-турски-съюз/. Last accessed 22 July 2016.

[72] https://www.24chasa.bg/mnenia/article/5655149. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[73] Taraclia is a majority ethnic Bulgarian (65.6%), almost wholly Orthodox (94.3%) district (raion) in southern Moldova bordering the Ukrainian Odessa Oblast’s Bolhrad Raion. The Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova, which is the majority party (69.6%) party in Taraclia, advocates a formal legal status for the district on the model of the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia. It alleges the Moldovan Parliament is seeking to attach Taraclia to the adjacent Cahul Raion, the effect of which it claims would be to reduce the position of Taraclia’s 44,000 ethnic Bulgarians to a minority within a district in which 93,000 Romanian Moldovans today comprise a majority (78.1%).

[74] VMRO.bg (20 July 20160, op cit..

[75] Mr. Karakachanov’s comment about “the Chief Mufti’s office” is a reference to Mustafa Aliş Hacı (the Bulgarian transliteration of his last name is Hadzhi), who in January 2016 ran unopposed for his third term as Chief Mufti of Bulgaria. Critics including Chief Mufti Hacı’s predecessor, Nedim Gendzhev, have warned against rising Turkish influence in Bulgaria through means such as the Turkish government’s funding (through the Chief Mufti’s office) schools and cultural institutions for Bulgarian Muslims (a practice the Chief Mufti’s office claims is permissible under a 1999 bilateral agreement).

[76] 24 Chasa (19 July 2016), op cit.

[77] “Karakachanov: Svetŭt se vrŭshta v situatsiya na Studena voĭna.” VMRO.bg [published online in Bulgarian 12 July 2016]. https://www.vmro.bg/каракачанов-светът-се-връща-в-ситуация-на-студена-война/. Last accessed 22 July 2016.

[78] “Karakachanov: Prezident – patriot, a ne evroatlanticheski papagal.” VMRO.bg [published online in Bulgarian 11 July 2016]. https://www.vmro.bg/каракачанов-президент-патриот-а-не-евроатлантически-папагал/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[79] Aleksandr Dugin (1997). Osnovy geopolitiki: Geopoliticheskoe budushchee Rossii. (Moscow: Arktogeya) 103. Radenko Scekic elaborates Dugin’s anaconda simile as “the idea that the ultimate goal of the US policy (implemented through a whole range of international organizations, of which the most dominant is NATO) was to round off, and then lead to political and economic collapse of its antagonists on the Eurasian land mass, especially Russia and China.” [85] He continues “Mackinder claimed that European countries did by sea what, e.g., Alexander of Macedon did by land. They got around, and then surrounded their opponents, taking under their control key coastal points. Thus was born the famous strategy of ‘anaconda’, which opponents of the Atlantic powers still see as a fundamental orientation of the Anglo-American geopolitical efforts.” [86] See: Scekic (2016). “Geopolitical Strategies and Modernity: Multipolar Worlds of Nowadays.” Journal of Liberty and International Affairs. 1:3. https://e-jlia.com/papers/3_7.pdf. Last accessed 25 July 2016. Dugin draws on the German Geopolitik theorist Karl Hauhofer, who argued that a continental Eurasian bloc (which he saw as Germany, Russia, and Japan) could counter a sea-based anaconda strategy intended, writes Natalia Morozova, “to envelop, engulf and choke Eurasia.” See: Haushofer (1924). Geopolitik des Pazifischen Ozeans. Studien über die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Geographie und Geschichte. (Berlin: Kurt Vowinckel Verlag). See also: Natalia Morozova (2011). “The Politics of Russian Post-Soviet Identity: Geopolitics, Eurasianism, and Beyond.” https://stage1.ceu.edu/sites/pds.ceu.hu/files/attachment/basicpage/478/nataliamorozova.pdf. Last accessed 25 July 2016.

[80] Dugin (1997), op cit. The text also appears in his 2009 book, Chetvertaya Politicheskaya Teoriya (“The Fourth Political Theory”). (Moscow: Amphora) 4.2.2. Heartland i Yevropa.

[81] Dugin (1997), op cit., 168.

[82] VMRO.bg (20 July 2016), op cit.

[83] VMRO.bg (15 July 2016), op cit.

[84] “Krasimir Karakachanov: Iskam da popravya schupeniya most mezhdu Ataka i NFSB.” VMRO.bg [published online in Bulgarian 9 July 2016]. https://www.vmro.bg/красимир-каракачанов-искам-да-поправя-счупения-мост-между-атака-и-нфсб/. Last accessed 22 July 2016.

[85] Valeri Simeonov is the leader and a cofounder of the VMRO-BND’s coalition partner, the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (Natzionalen Front za Spasenie na Bulgaria).

[86] Its chair, Nikolay Malinov, claimed 35,000 signatures on a petition opposing the deployment of NATO missiles in Bulgaria. Messrs. Malinov and Stanilov were quoted by the Russian Institute of Strategic Studies. See: “Ekspert RISI prinyal uchastiye v s”yezde rusofilov Bolgarii.” RISS [published online in Russian 15 June 2016]. https://riss.ru/events/31606/. Last accessed 20 June 2016. The Russian Institute of Strategic Studies (sometimes called by its transliterated Russian acronym, RISI) functions as a Kremlin think tank. Now an administrative unit of the President’s office, it was formerly part of Russia’s external intelligence agency, the Sluzhba vneshney razvedki (SVR).

[87] “Samo ATAKA protiv razshiryavaneto na NATO v Cherna gora.” Rusofili.bg [published online in Bulgarian 30 June 2016]. https://rusofili.bg/само-атака-против-разширяването/. Lasr accessed 21 July 2016.

[88] “ATAKA protiv zakupuvaneto na stari iztrebiteli F-16.” Rusofili.bg [published online in Bulgarian 3 June 2016]. https://rusofili.bg/атака-против-закупуването-стари-из/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[89] The acronym of the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (Natzionalen Front za Spasenie na Bulgaria), which is the VMRO-BND’s Patriotic Front coalition partner.

[90] ” Karakachanov: Patriotichnite formatsii iskame da se yavim s edna obshta kandidatura na prezident·skite izbori.” VMRO.bg [published online in Bulgarian 15 July 2016]. https://www.vmro.bg/каракачанов-патриотичните-формации-искаме-да-се-явим-с-една-обща-кандидатура-на-президентските-избори/. Last accessed 21 July 2016.

[91] Ibid.

[92] “Kak umirayet Bolgariya: YES, samosozhzheniya, rusofobiya i rusofiliya.” Rusvesna [published online in Russian 31 May 2016]. https://rusvesna.su/recent_opinions/1464600694. Last accessed 17 July 2016.

[93] “DPS zashtiti Turtsiya, GERB poiska da ne vzimame strana.” Dnes [published online in Bulgarian 25 November 2015]. https://dnes.dir.bg/news/rusia-dps-vazdushno-prostranstvo-turtzia-svali-rusci-samolet-20821304. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[94] “Ofitsialno: 3,5 miliona bŭlgari zhiveyat izvŭn Bŭlgariya.” 24 Chasa [published online in Bulgarian 25 May 2016]. https://www.24chasa.bg/novini/article/5530895. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[95] “Kak bolgarskaya oligarkhicheskaya elita predala Rossiyu.” Center for Political Analysis [published online in Russian 21 October 2014]. https://centerforpoliticsanalysis.ru/archive/read/id/kak-bolgarskaya-oligarhicheskaya-elita-predala-rossiyu. Last accessed 19 July 2016.

[96] “Bulgarian prime minister is Brussels’ ‘golden boy’.” Deutsche Welle [published online 28 May 2016]. https://www.dw.com/en/bulgarian-prime-minister-is-brussels-golden-boy/a-19285290. Last accessed 23 July 2016.

[97] “Krasimir Karakachanov: Promenite v Zakona za veroizpovedaniyata tselyat prekratyavaneto na opitite na Turtsiya chrez religioznite institutsii na myusyulmanite da se bŭrka v suverennite raboti na Bŭlgariya.” Focus-news.net [published online in Bulgarian 21 July 2016]. https://www.focus-news.net/news/2016/07/21/2272022/krasimir-karakachanov-promenite-v-zakona-za-veroizpovedaniyata-tselyat-prekratyavaneto-na-opitite-na-turtsiya-chrez-religioznite-institutsii-na-myusyulmanite-da-se-barka-v-suverennite-raboti-na-balgariya.html. Last accessed 24 July 2016.

[98] “Patriotichniyat front iska da se zabrani na chuzhdentsi da izvŭrshvat propovedi.” BG Regioni [published online 22 July 2016]. https://bgregioni.com/2016/07/22/патриотичният-фронт-иска-да-се-забран/. Lasty accessed 24 July 2016.

[99] “Valeri Simeonov: Islyamŭt u nas e forma na namesa na Turtsiya vŭv vŭtreshnite raboti na Bŭlgariya.” Velika Bulgaria [published online in Bulgarian 24 July 2016]. https://velikabulgaria.eu/валери-симеонов-ислямът-у-нас-е-форма-н/. Last accessed 24 July 2016.

[100] “Ne mozhem da se nadyavame nito na NATO, nito na ES

Vasil Vasilev: Nuzhen ni e Balkanski pakt, koĭto da ni zashtiti ot turska invaziya!.”