A nation must think before it acts.

(Source: VargaA/WikiMedia Commons)

Russia’s neighbors are on high alert: the unexpected annexation of Crimea, the stealth intervention in eastern Ukraine, and the emergence of the Novorossiya project have heightened the perception of the growing Russian military threat in the region and beyond. Will Moldova be the Kremlin’s next target? When it comes to perceiving Russia as a threat, politicians in Moldova are divided between two extremes: threat inflation and threat deflation. Deflators are situated usually on the Left, while inflators are found generally on the Right. Whereas public perceptions of the Russian threat may be intentionally manipulated by politicians, the increasing dysfunctionality of the Moldovan state is as real as it gets. Three aspects of state weakness in Moldova—the excessive influence of oligarchs, the pervasiveness of Soviet nostalgia among the population, and the Transnistrian issue—may smooth the way for foreign interference by Russia.

Inflating and Deflating the Foreign Threat

Mihai Ghimpu

Both threat inflators and deflators misrepresent reality. Such distortions may be the result of unconscious cognitive errors and motivated reasoning. Threat inflators cry wolf too often. These politicians amplify the Russian threat and label their political competitors as Russia’s agents in order to deflect the public’s attention from pressing domestic problems. The most prominent example includes Mihai Ghimpu, the leader of the right-wing Liberal Party. In a recent TV show, Ghimpu, with no shred of evidence, suggested that the Action and Solidarity Party (PAS) led by Maia Sandu has close ties to Moscow. Many smaller right-wing political parties do not hesitate to label their opponents as Russia’s fifth column. When it is convenient for them, centrist politicians use the same tactics. In October 2016, Andrian Candu, the Speaker of the Parliament, claimed that Russia is financing certain political parties and supporting anti-government protests. Because threat inflators regularly invoke Russia’s interference in domestic politics, the threat itself has become an object of popular ridicule.

By contrast, threat deflators ignore the issue altogether, seeking publicly to legitimize Russia’s intervention in Ukraine and the Kremlin’s foreign policy more generaly. The Moldovan Socialist (PSRM) and Communist (PCRM) Parties fall into the threat deflator category. What explains the Russian threat deflation among left-wingers? Multiple causes may be at play. First, certain politicians use threat deflation strategically to attract the support of Russian-speaking voters, who often hold extremely positive views of Russia. Take, for instance, Igor Dodon, the current Moldovan president and member of the Socialist Party. During his election campaign, he refused stubbornly to criticize Russia’s annexation of Crimea, triggering a critical diplomatic response from Ukraine. Second, threat deflation may be part of a quid pro quo arrangement for receiving financial support. A recent journalistic investigation revealed that the PSRM accepted funds from Russia via a group of companies registered in the Bahamas. Of course, the third type of threat deflators includes the so-called true believers. Such individuals perceive the political reality largely through the ideological lens of the state-owned Russian media broadcasting in Moldova. Threat deflators are not necessarily peace-loving citizens. They often depict Romania and the West as existential threats. The new president, Dodon, removed the EU flag from the presidential palace, promised to cancel the EU-Moldova Association Agreement, and revoked the Moldovan citizenship of Traian Băsescu, the former Romanian president.

In the cases described above, politicians manipulate intentionally the gravity of the foreign threat in order to influence public opinion for political gain. Undoubtedly, the threat exists. A resurgent Russia annexing territories belonging to neighboring states remains a serious cause for worry, especially for Moldova, a tiny neutral state located beyond the reach of NATO’s security umbrella. Nevertheless, threat inflation and deflation should not divert our attention from Moldova’s central problem: state weakness.

Weak States Attract Bullies

Weak states are more vulnerable to foreign interference. Since its official declaration of independence in August 1991, Moldova has suffered from chronic state deficiency. Symptoms of Moldova’s malaise are an underfinanced army, low tax revenue, extreme poverty, large-scale emigration, competing national identity projects, and lack of sustainable innovation-driven economic growth. In the context of the recent regional turbulence, three other issues—oligarchic state capture, bizarre public opinion trends, and the unresolved Transnistrian conflict—aggravate the problem of foreign interference.

Vlad Filat (Source: Michał Koziczyński/Senat Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej)

First, in 2009, the state was captured by oligarchs and has been exploited by them ever since. Aided by incompetent bureaucrats and politicians, oligarchs coordinated an epic theft from the Savings Bank of Moldova (BEM), Banca Sociala, and Unibank. Parties controlling the state-owned BEM, the major bank in the system, extracted resources by directing a stream of credits to politically connected firms with ties to offshore jurisdictions. Once the situation at BEM worsened dramatically, the government ceded its control of the bank in favor of a group of minority shareholders backed by Prime Minister Vlad Filat. The new owners, however, continued to syphon off funds. When there was nothing left to steal, they invoked the too-big-too-fail logic forcing the government to bail the banks out. The declassified minutes of the government meetings at which the two bailouts were granted (bailout 1 and bailout 2) reveal that over one billion USD was transferred from the National Bank of Moldova to the three banks to avoid massive bank runs. As a result, the oligarchs left the state heavily indebted, lacking resources to spend funds on defense and security. While the ensuing societal outrage and inter-oligarchic conflicts enabled state institutions to act autonomously and arrest the main culprit, Vlad Filat, the arrest did not free the state from oligarchic influence. Instead, it increased the informal influence over the state of the second major oligarch, Vlad Plahotniuc.

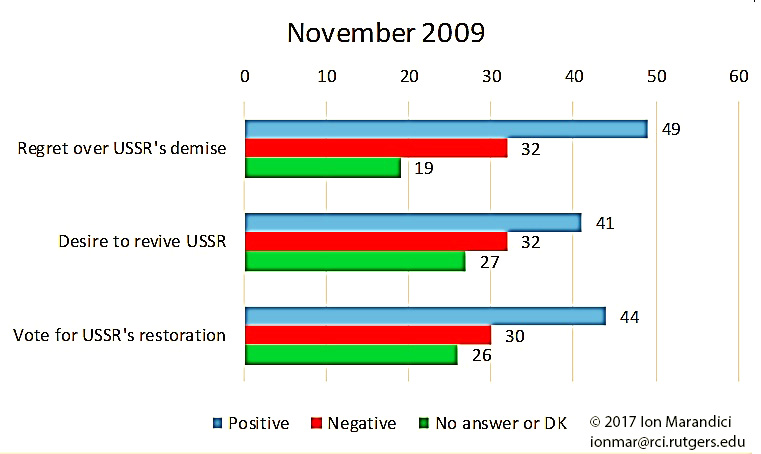

Second, two public opinion trends—high levels of Soviet nostalgia and a high degree of trust in Vladimir Putin—clearly favor outside interference. Survey after survey shows that Moldovans display nostalgia for the Soviet state. In 2009 and 2016, the Barometer of Public Opinion asked respondents whether they regret the demise of the Soviet Union, whether they desire to revive the Soviet state, and whether they would vote in a referendum in favor of the restoration of the USSR.

The two graphs above indicate that the Moldovan public became more nostalgic for the USSR over time. In 2016, 49.4% would have voted in favor of Soviet restoration, while only 27.9% would have voted against it. Support for an eventual restoration is higher in 2016 compared to support in 2009. While such data should be interpreted with care, they may suggest that some Moldovans are willing to renounce their recently obtained independence. The second inexplicable trend concerns the high trust enjoyed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moldova. In November 2009, 74% of respondents expressed trust in him. In the aftermath of Crimea’s annexation, seven years later, 66% viewed him as trustworthy. Trust in this authoritarian figure is higher than trust in Moldovan politicians (see the Barometers of Public Opinion). Such tendencies among voters are puzzling, and that is why policymakers need to reflect more on whether these persisting inclinations of the public invite foreign interference.

Third, there is Moldova’s Transnistria problem. The current ruling elites in the breakaway Transnistria lack any loyalty whatsoever to the Moldovan state. Instead, public displays of devotion to the Russian state are the norm. Local politicians constantly invoke the 2006 referendum in which, according to Transnistrian authorities, 98% of the participants opted for future unification of the region with Russia. Because the region survives thanks to the generous subsidies flowing from the Russian state, systematic pledges of loyalty became the sole requirement for receiving free “goodies” from Moscow. In December 2016, the main contenders in the last presidential elections, V. Krasnoselsky (the winner) and V. Shevchuk (the incumbent-loser), rejected any future integration with Moldova, emphasizing, instead, Transnistria’s future as a part of Russia.

No Quick Fixes in Sight

There are no easy fixes for Moldova’s domestic problems. The state capture problem could be moderated by adopting state-building reforms, enhancing the autonomy of the state vis-à-vis the oligarchs. Putting in place safeguards against excessive informal oligarchic influence, consolidating the independence of the courts, and insulating the investigative-coercive governmental structures from political interference would increase the state’s ability to resist oligarchic and political pressures. Likewise, the drivers behind the high levels of Soviet nostalgia and the high trust in a foreign authoritarian figure should be properly researched and understood before any meaningful policy recommendations can be proposed. Lastly, keeping the Transnistrian conflict frozen for the next decade and intensifying bilateral cooperation with Ukraine seem more realistic policy options than wasting limited public resources on re-integrating the breakaway region.

The worst-case Ukraine-style scenario could play out in Moldova only if local disaffected groups mobilize against the state, providing a convenient pretext for Russia to intervene militarily.