A nation must think before it acts.

(DOD photo by U.S. Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Dominique A. Pineiro)

As most of China returned to work after the long Golden Week holiday, heightened security measures were put into place in Beijing, the nation’s capital. All police leaves were cancelled, and thousands of additional security personnel were brought into Beijing to guard against what the media delicately refer to as “social instability.” Identification cards were checked not only in and near public buildings, but even in subway stations. All Airbnb contracts were cancelled, and drone flights prohibited. Media censorship, scarcely lax before, became yet more vigilant. A film with a sensitive theme had its opening postponed. Heavy industry was ordered to scale back production to ensure blue skies, and funds were injected into the stock market to guard against fluctuations.

The reason for these extraordinary measures was the every-five year meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This iteration, the Party’s 19th, saw over 2,200 delegates converging on Beijing to “elect” a new Central Committee of the party. Despite the aura of secrecy about what would be announced, most analysts agreed that final decisions were likely to have been made at a prior gathering weeks before.

Outside China, views on the meeting varied, from Harvard professor Graham Allison’s adulatory essay entitled “Behold the New Emperor of China”—with no hint of sarcasm evident—to Oxford don Stein Ringen’s description of a ruthless dictatorship. Australian analyst Kevin Carrico, predicting a lengthy set of ritualistic speeches, said the congress would be much ado about nothing.

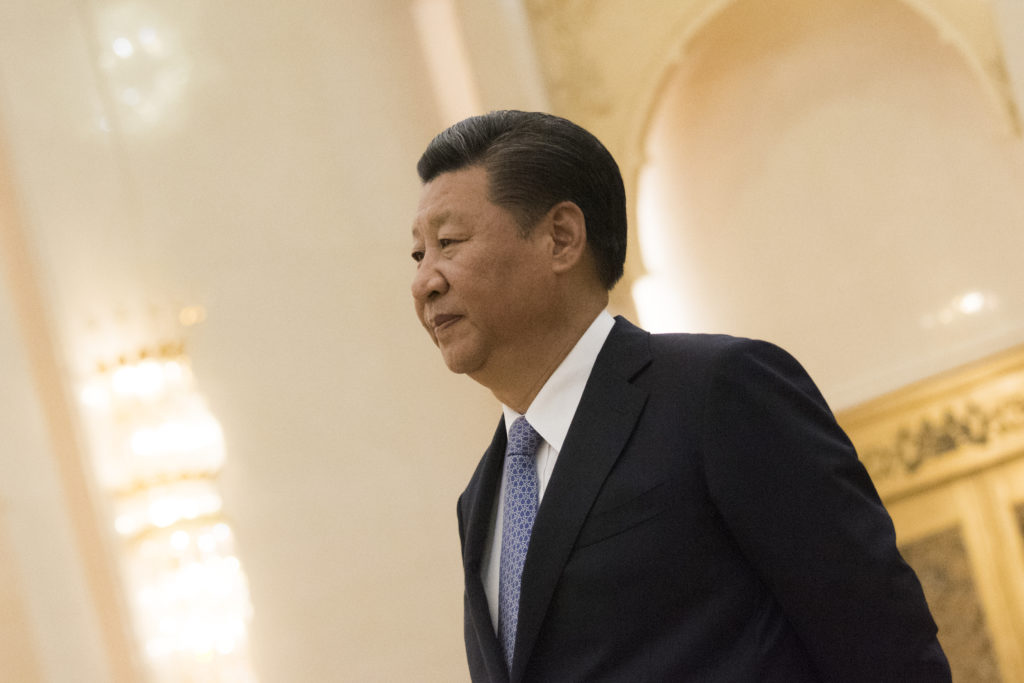

All about Xi

To be sure, the major issue, Party General Secretary Xi Jinping’s re-appointment to a second five year term, was uncontested. Although rumbles of discontent were noticeable little more than a year ago, they were quickly silenced. Xi set up several “leading small groups” to take charge of specific policy areas, with himself head of each and, in the course of a campaign to root out corruption at levels high and low (“tigers and flies”). Claiming 1.5 million victims so far, the campaign seemed to have eliminated all potential rivals. These ranged from provincial leaders to military men through the justice ministry. Two leading generals were charged with abuse of office, which generally means taking bribes in exchange for promotions. The party secretary of the provincial-level city of Chongqing was found guilty of leaking confidential CCP information, seeking benefits for his relatives’ businesses, and accepting huge amounts of money and gifts.The justice minister was found to have “serious discipline problems”—a euphemism for corruption—removed from her position, and expelled from the Party as well. These moves have not always been met with supine compliance: the erstwhile party secretary of Chongqing was alleged to have been active in plans for a counter-regime coup d’état.

Xi had also encouraged a cult of himself: portraits of Xi, often with his photogenic spouse Peng Liyuan, adorned a variety of pictures and ceramic plates for sale in open-air shops, typically edging out those of perennial favorites Mao Zedong and the Buddha. He put forth his plan for a “China Dream” for national power and prosperity, published a widely-distributed (though not necessarily widely bought or read) book of his thoughts, and paid unannounced—albeit well-publicized—visits to dumpling shops to mingle with awed ordinary patrons, apparently relishing, at least for a time, being called “Xi Dada,” or Daddy Xi. Already a year ago, in October 2016, a Party meeting had officially designated Xi a “core” leader, a level of reverence previously according only to Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. What could possibly go wrong?

As is the case with leaders worldwide, Xi’s opening speech to the assembled delegates promised a rosy future. The past five years had seen great progress: even greater triumphs lay ahead. By the middle of the 21st century, China would be a “prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful country. “ The People’s Republic would be wealthier, cleaner, and militarily more powerful, moving to center stage in the international order.

While the coronation was not in doubt, speculation had been rampant on a number of other issues. First, since Xi was expected to retire after the end of his second term, would he, as rumored, seek to stay on longer or—in a signal that he did intend to step down—indicate his choice for a successor?

If so, would the delegates ratify the individual? This had not always been the case: in 2007, Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, made it clear that he preferred someone from his own faction, the Communist Youth League (CYL or tuanpai), Li Keqiang, to succeed him. But Li came in second to Xi, who did indeed receive the top post when Hu retired in 2012. Li had to settle for premier, the highest position in state government, where Xi proceeded to all but ignore him. Failure to ratify Xi’s choice seemed an unlikely scenario this time: he had essentially dismantled the CYL, absorbing the China Youth University of Political Studies, its flagship institution for training future league officials, into the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and renaming it the University of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Second, who would be the other members of the CCP’s inner sanctum, the Standing Committee of the Politburo (PBSC)? This group, seven during the just-ended party congress, has had as few as five members and as many as nine in the past. The organizations in which PBSC members have served and with whom they are thought to be affiliated have been a matter of intense scrutiny. Under an informal, but generally observed, rule—commonly referred to as the “seven up eight down” rule—that is meant to provide periodic infusions of new blood into the leadership, those who are 68 or older at the time of the Party Congress, and would therefore be 73 at the end of their five-year terms, are expected to retire; those who are 67 or younger may stay.

Under Xi’s first term, all the members of the PBSC save for Li Keqiang were considered allies of Xi. But assuming the “seven up eight down” rule were observed, all but Li would be required to resign. The 25-person Politburo, from which the new PBSC is normally derived, contained a more diverse group of individuals. And among the five scheduled to retire was the 69-year old redoubtable Wang Qishan who, in addition to being close to Xi, had run his anti-corruption campaign. Were Wang to be kept on and the 7 up 8 down rule ignored, that would be taken as a signal that Xi himself planned to stay on after 2022.

So as well would his failure to appoint a younger person, i.e. one who would be young enough to serve a full ten-year term as president, when appointed in five years. One of the few such persons in the Politburo eligible to do so was the aforementioned discredited Party Secretary of Chongqing, Sun Zhengkai. His successor in Chongqing, Chen Min’er, is 57 and therefore able to serve a full ten-year term. But he was not yet a Politburo member, meaning that promotion directly into the PBSC would have been abnormal.

Finally, and to some most crucially, there was the matter of amending the CCP’s constitution. This is typically done as or after a leader retires, according to a carefully considered hierarchy. Marxism Leninism comes first, then Mao Zedong thought, meaning that Mao was not accorded the status of “ism,” and Deng Xiaoping theory, a level considered below thought. The next leader, Jiang Zemin, reportedly tried hard to get his name included, but had to settle for the Theory of Three Represents, and Hu Jintao for his signature phrase, the scientific outlook on development.

A True Coronation?

In the end, Xi succeeded in enshrining his name and status in the party constitution at a level equal to Mao’s: the newly approved formula is Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, the Scientific Outlook on Development, and Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. A phrase that cries out for an acronym.

However, Wang Qishan has retired not only from the Standing Committee of the Politburo, but also from the Central Committee, thus leaving the seven up eight down rule intact. Another confidante of Xi, Zhao Leji, has entered the select group and took over Wang’s responsibilities as head of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

The number of PBSC members remains at seven, though none is below the age of 60, meaning eligible for a full ten year term after the 20th Party Congress five years hence. Xi has thus not designated a successor, reinforcing suspicions that he intends to break the two-term rule by staying on past 2022. Conceivably, Chen Min-er could be promoted into the PBSC mid-term, but this would be highly unusual. The new members have worked with Xi before, though not all—for example, the reform-minded former head of Guangdong province—are considered closely associated with him or his programs.

In short, the new configuration represents a de-institutionalization of the leadership structure, leaving Xi Jinping firmly at the top. Supporters point out that this concentration of power will allow faster progress toward implementing the restructuring of an ossified system. Critics argue that the result represents a regression toward fascism—some have used the character for Xi’s surname to transliterate references to Hitler—under a leader who will permit no dissent. Also that such a strongly top-down system is unsuited to the technologically complex system that China has become. Moreover, if Xi’s efforts at reform should fail, his critics will hold him directly responsible.

So, the outcome of the Congress was something only slightly less than Allison’s coronation. Although the speeches were indeed as boring as Carrico predicted, the Congress was not quite anticlimactic. And has perhaps fallen a bit short of Ringen’s ruthless dictatorship. Chinese politics will continue to surprise.