A nation must think before it acts.

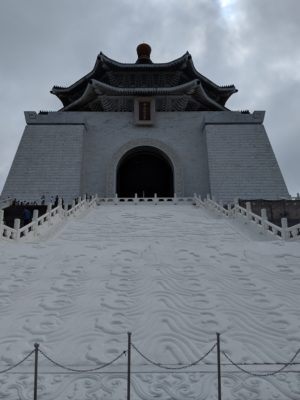

On a recent research to Taiwan, I made several visits to one of the premiere tourist attractions in Taipei: the Chiang Kai-shek (CKS) Memorial Hall, which memorializes the “Generalissimo” who ruled (in various forms) the Republic of China from 1928-1975. The Hall would remind Americans of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., due to its grandiose style and architecture and the presence a large statue of the titular leader sitting in a chair. I visited the location many times because I am undertaking a research project on the Tsai Ing-wen administration’s transitional justice (TJ) initiatives to address Taiwan’s authoritarian past under the Kuomintang, and the Hall is one of the major points of controversy since as a part of the TJ efforts, the government is reviewing the status of statues of CKS and debating what to do with them.

As a part of my project, I conducted interviews with members of government, academia, the Transitional Justice Commission, and the Ill-Gotten Party Assets Settlement Committee, and toured relevant museums and sites such as the mausoleums of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of CKS who succeeded him as president of the Republic of China/Taiwan and who is often given credit for democratizing the country. I will be returning to Taiwan for a second trip in a couple of months to conduct more interviews. For my project, I will be writing a number of articles—on what to do with statues of CKS, U.S.-Taiwan relations, and the importance of transitional justice for Taiwan’s image—and a longer report on the history of the February 28 Incident and the martial law/White Terror period that ensued and the initiatives that previous governments and the current one have carried out to address past atrocities. So stay tuned for more throughout the next few months. But before I write on these more serious and controversial topics, I would like to tell you about an odd and humorous occurrence on my first day back in Taiwan since 2016.

Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

My plane had arrived around 6:00 in the morning, and I could not check in to my hotel until 3:00 in the afternoon, so I had several hours to kill after taking a 16-hour flight from New York City. As a former resident of Taipei, I knew that CKS is great for killing time since there are plenty of things to see; places to relax; benches to close your eyes on; and cafes to gulp down cups of coffee. CKS Memorial Hall is surrounded by beautiful gardens that senior citizens use to practice tai chi, that students use to practice dance routines, and that others use to improve the quality of their Instagram accounts; it is also just a nice shaded place to relax in the center of Taipei. Tourists particularly enjoy watching the hourly honor guard change. But on my first visit back to the Hall, I was not interested in any of these things. And perhaps most importantly for my purposes on this particular day, there are several museum spaces in the “belly” of the Hall underneath the famous statue and viewing gallery.

Garden in the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall complex (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

The one that attracts many tourists is the museum on the life of CKS. It has pictures, documents, awards, his cars, as well as two display cases on his favorite dishes—in case you’d like to start the “Generalissimo Diet.” The plastic food looked pretty appetizing after only eating airplane food for the past day. This museum provides a nice history—however skewed to make CKS look as positive and heroic as possible—of China and Taiwan.

Some of Chiang Kai-shek’s favorite foods (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

Some of Chiang Kai-shek’s favorite foods (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

Most conspicuously, there is a special Andy Warhol exhibit in the basement. For about $10, visitors can view some of Warhol’s most famous works: the Campbell’s soup can, magazine covers, Marilyn Monroe, etc. As jetlagged as I was at the time, the peculiar nature and irony of seeing Andy Warhol artwork just below the supposed paragon and savior of “Free China” did not escape me. All of my brain cells hadn’t snapped … yet. I couldn’t believe seeing a special exhibit for a famously edgy and radical artist being housed in the Memorial Hall of a conservative Chinese leader that the American government propped up for so many years in an effort to stop Communist expansion during the Cold War. I think CKS and Mr. Warhol would agree with my assessment.

Entrance to the Andy Warhol exhibit (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

But, it gets weirder.

Warhol’s famous portraits of Mao Zedong hang along one wall in the exhibit. Warhol had made these colorful portraits after Nixon’s shocking visit to China; he had dubbed Mao “the most famous person on earth.” Some of the portraits even depict Mao wearing lipstick.

One of Andy Warhol’s portraits of Mao Zedong (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

One of Andy Warhol’s portraits of Mao Zedong (Photo: Thomas J. Shattuck)

The last thing that I ever expected to see on display in a museum below the most famous likeness of CKS was Mao Zedong—lipstick or no. When I first saw the portraits on display, I had to do a double-take. It couldn’t be. The jetlag finally got to me. But no, there truly is a wall of Warhol’s Mao on display at CKS Memorial Hall—until April for those who are also interested in having an out-of-body experience.

The conflict between Mao and Chiang dates back to before World War II when the Communist and Nationalist forces fought each other in China. Mao would call Chiang a “reactionary clique” and “paper tiger.” And he eventually defeated CKS and his Nationalist army that had the advantage of American support. Chiang also shared his own barbs about Mao. Even though Japan had invaded Manchuria in 1931, Chiang’s philosophy of warfighting was “the Japanese are a disease of the skin, the Communists are a disease of the heart,” demonstrating that despite the Japanese military threat, he still wanted to focus on the Communists. And for years after he fled to Taiwan after the 1949 civil war defeat, CKS believed that he could retake the Mainland and defeat the Communists (he never did). The relationship between CKS and Mao had many peaks and valleys: rivals, sometimes partners, and then bitter enemies.

It was quite a pairing, going from viewing CKS’s favorite foods to viewing famous portraits of Mao, particularly at a time when CKS is under assault for his actions during the martial law and White Terror period in Taiwan. It was a nice reminder on my first day back in Taiwan that you never know what you’re going to see there. And it was an auspicious start to my project.