A nation must think before it acts.

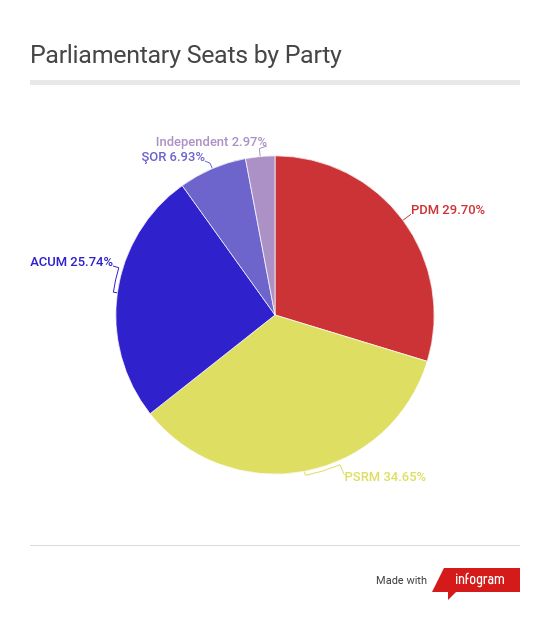

The February 2019 Moldovan parliamentary elections might seem like a story of triumph against adversity and the victory of an underdog. A small party that had single-digit ratings a few months ago managed to rally at the polls. Now, that party has 30% of the seats in parliament and is almost certain to enter government.

No, this is not the story of the fledgling anti-corruption ACUM coalition, but the story of the Democratic Party of Moldova, led by the infamous oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc. The Democrats’ surprising comeback is no accident. It is the product of sophisticated techniques of political and electoral manipulation. These techniques allowed the Democrats to turn their control of government—both parliament and the supposedly non-political agencies—into more votes and more seats. This election was not fought over issues; it turned on power, patronage, and material interests.

Democracy and the Democrats

The Democratic Party was founded in 1997 and has been under Plahotniuc’s control for the past decade. In 2014, it won 19 out of 101 seats as part of the Alliance for European Integration. In 2015, it was discovered that $1 billion, or one-sixth of Moldova’s GDP, was missing from the country’s banking system. The scandal led to the arrest of Prime Minister Vlad Filat and undermined support for the Alliance. In popular opinion, the Democrats suffered with the rest of the Alliance—but in parliament, they benefitted. Deputies jumping ship from Filat’s party joined the Democrats, gradually bringing the party to 41 seats. The Democrats became the senior Alliance partners in 2016, and, by 2017, they ruled alone as a minority government.

The Democrats were not the only party to benefit from the billion-dollar theft, which provoked massive protests in the center of Chisinau, the country’s capital. Parliamentary deputy Igor Dodon leveraged his role as a protest leader to win the 2016 presidential election. Meanwhile, polls indicated that his pro-Russian Party of Socialists, which served as parliamentary opposition to the Alliance, had become the most popular party in Moldova. On the other side of the political spectrum, pro-European protest leaders Maia Sandu and Andrei Năstase built new political parties on anti-corruption platforms. They presented a serious threat to the status quo, with Sandu a close second to Dodon in the 2016 presidential election. Knowing that they would struggle to win seats separately, they entered the 2019 parliamentary elections as the ACUM coalition.

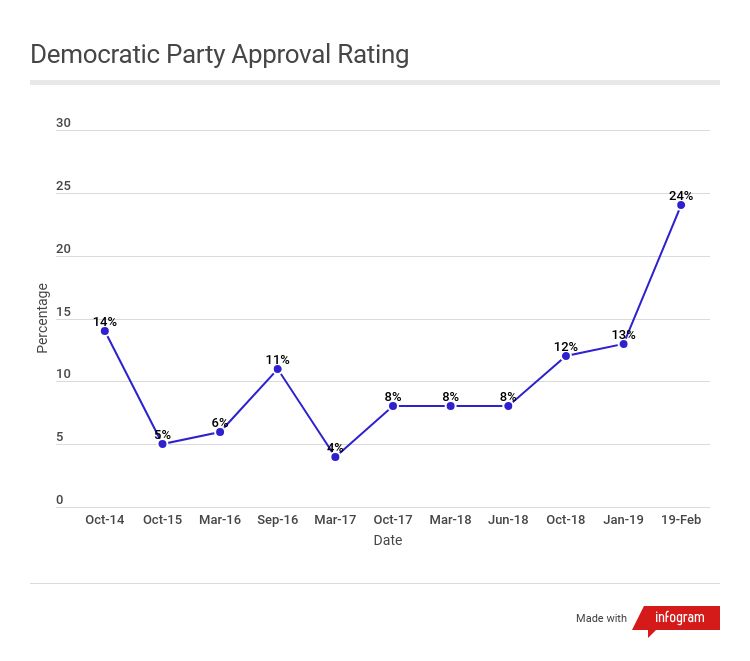

Compared to polls from a year ago, the Democrats’ election results are surprising. In March 2018, the Socialists were the clear favorites with a 32% rating. In February, they won 35 seats out of 101. The two parties that combined to form ACUM had the support of 22% of poll respondents and received 26 seats. The Democrats, however, were polling at 8% a year ago, but won 30 seats.

The Democrats accomplished this feat through legal—but not democratic—means. More than just a party in power, the Democrats aspire to be the party of power, a Russian term for a political party that holds elected office and also commands the loyalty of unelected, supposedly apolitical bureaucrats. A party of power follows democratic laws and procedures on the surface, yet undermines political competitiveness and the rule of law. The Democrats ran an election campaign like any other party. But they also used their formal and informal control of government to influence the results. Their success indicates that Moldova is on its way to a system that is democratic in form, but non-democratic in substance.

How to Buy Friends and Influence Elections

The foundation for the Democrats’ victory was laid in 2017 when the party orchestrated a change in Moldova’s electoral system. Since the early 1990s, Moldova has used a closed-list proportional representation system, in which citizens vote for parties but cannot choose individual candidates. Parliamentary seats are allocated to parties in proportion to the number of votes they win. In May 2017, however, the Democrats and the Socialists voted together to change the electoral system to a mixed-member parallel system. Half of the deputies are now elected by proportional representation and half are elected in American-style single-member districts, in which the candidate with the most votes wins.

The Democrats benefitted from the new electoral system because single-member districts allowed them to mobilize voters in ways that only a party of power can: through propaganda, control of local governments, and vote buying. A party running in a national proportional representation election must appeal to voters nationwide in order to win a higher percentage of the national vote and, therefore, more seats. In first-past-the-post district elections, however, the candidate only has to win one more vote than her closest rival. A party of power can also buy votes in more concentrated areas—areas it can also win over through targeted public spending. Single-member districts allow the dominant party machine to convert its disproportionate resources into parliamentary seats as efficiently as possible.

With electoral reform in place, the Democrats exploited their control over government to generate support. Over the course of a year, they launched a propaganda campaign lauding the successes of their time in power and pushed pension and salary increases through parliament. Plahotniuc was explicit in tying these bills to the election; for example, he held hostage one bill on free medicine by scheduling the first reading for before the election, but pointedly delaying the second reading until after the election. He seemed to be implicitly threatening that the Democrats would use their control of state benefits to reward supporters and punish detractors.

The Democrats’ control of governmental agencies gave them an edge other parties did not have. City workers attended rallies and campaigned while on the clock. High-level civil servants traveled around the country in Democratic Party campaign buses. Electricity bills sported advertisements for a Democratic candidate. These tactics were not intended simply to raise support. They also signaled to voters that the Democratic Party was the party of power, capable of using government resources for private benefit—and getting away with it.

Data from IRI Moldova, percent of likely voters responding “Democratic Party” to the question, “What party would you vote for if parliamentary elections were held next Sunday?” The February 2019 figure represents Demcratic vote in the PR tier of the 2019 election.

The manipulation continued on the day of the election. Vote buying was extremely prevalent and was noted by both domestic and international observers. Several parties engaged in vote buying, but only the Democrats could support their operation with governmental power. For example, ballot secrecy makes vote buying difficult because it prevents candidates from verifying that the voter held up his end of the bargain. One tactic used by the Democrats was, therefore, undermining the perception of ballot secrecy. For the first time, the Central Electoral Commission had video cameras installed at polling stations. Although these cameras were supposedly meant to prevent fraud, the message many took away was that those in power would be able to observe their votes. Similarly, reports on social media indicate that party officials called voters with information that should only have been accessible from the Central Electoral Commission’s database—implying that they might also be able to find out who voted for which party. This should be impossible under Moldovan election law, but the Democrats did not actually need to compromise ballot secrecy. They only needed to create doubt in the minds of voters in order to facilitate intimidation and vote buying.

Democracy in Moldova

In isolation, many of these tactics are legal. Although observers documented the unusually high number of people taking photos of ballots and holding lists of names outside polling stations, it would be impossible to prove in court that the Democrats bought votes. Taken together, however, the evidence points towards a concerted attempt to undermine the fairness of the election. The new electoral system, combined with attempts to undermine ballot secrecy, facilitated vote buying. Propaganda and campaigning by nonpolitical officials reinforced perceptions that the Democratic Party controlled the levers of government. Expectations that the election would be manipulated made voters more amenable to selling their votes. Procedurally, the election was mostly fair; in substance, it was biased towards the Democrats.

The influence of a party of power rests on its control of governmental institutions, but it also rests on the expectation that the party of power will maintain its influence into the future. No rational bureaucrat will engage in fraud or corruption on behalf a losing party. After the 2019 elections, the Democrats have cemented their position as Moldova’s party of power. With loyalists in the constitutional court, city halls, National Bank, and even the electric company, the Democrats already control much of the Moldovan government. Winning seats in parliament, however, legitimizes Democratic rule. It creates the self-fulfilling expectation that the Democrats will continue to exercise proportionally more influence than their number of seats would suggest.

The Democrats’ actions are not without consequences. A €100 million aid package from the EU was delayed after the electoral system reform and put on hold during the summer, after a mayoral election won by ACUM’s Năstase was canceled. The European Parliament has so far refrained from making a statement about the parliamentary elections, but the political situation in Moldova has not escaped Brussels’s notice. Staying in power is, it seems, a higher priority for the Democrats than geopolitics.