A nation must think before it acts.

When addressing the case of Hoda Muthana, an American-born former ISIS member, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated, “Ms. Hoda Muthana is not a U.S. citizen and will not be admitted into the United States. . . . She’s a terrorist.” The judge ultimately denied Muthana’s citizenship because her father held diplomatic immunity at the time of her birth, meaning she was ineligible for birthright citizenship. However, Pompeo’s statement summarizes the departure of U.S. repatriation policies from the due process and rehabilitation-based programs set by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and indicates new concerns in U.S. national security. Currently, the DOJ has processed seven cases of former ISIS returnees and estimates over 20 American fighters remain in Syria and Iraq. Analysis of changes in American foreign policy also indicates the threats that uninformed and hypocritical decisions regarding former jihadists and the Syria conflict as a whole have created a variety of potential threats to U.S. national security. By neglecting the importance of foreign relations in national security, American foreign policy decisions have damaged the reputation of the United States and reduced its presence in areas of international importance. Therefore, policy deciding the repatriation of former ISIS members and related issues must equally address U.S. military concerns and relations with international actors.

Risking Alliances

The national security concerns of the United States manifest in two ways in response to the foreign fighter issue. Defense issues include violent results of re-radicalization, increased recruitment, and resurgence of ISIS. Foreign affairs concerns, however, address the potential distancing of allies as the U.S. continues to encourage unilateral action and withdraws from the international arena. This section will analyze how U.S. alliances have already been damaged by current policy, reducing opportunities for future agreements, and how the recent escape of ISIS prisoners acts as the intersection of both (i.e., defense and foreign affairs) aspects of U.S. national security.

Europe

Since early 2019, President Donald Trump has advocated for European powers to accelerate their repatriation efforts. This is an extremely difficult and involved feat because of the European Union’s restrictive citizenship system, which has become less flexible in response to increasing refugee flows. The United Kingdom has even revoked the citizenship of individuals seeking to return as a method of removing any responsibility. This response and similar policies come as a result of the comparatively higher number of ISIS attacks on European soil. Public disapproval rates are higher in countries that repatriate former terrorists, and a majority are opposed to accepting the children of ISIS members. President Trump responded to this resistance by threatening to release European fighters in the custody of the United States and Syrian Democratic Forces.

The uncontrolled and abrupt mass release of ISIS fighters poses a variety of threats to U.S. national security. First, any resulting attacks on European powers would impact the reputation of American military capabilities and would damage the principle of obligation. Furthermore, this opportunity could allow ISIS members to regroup and develop new tactics. New conflicts would increase the U.S. military presence in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The reemergence of ISIS could increase radicalization among U.S. and European citizens, and the terrorist group could find new members in the MENA region as a result of increased anti-American sentiment.

The Middle East

Increasing negativity towards the United States in the Sham region comes as a result of recent poor policy decisions. The U.S. military withdrawal seriously damaged the relationship with the Kurds and allowed for other states, primarily Russia and Turkey, to gain more control of the region. U.S. relations with these emerging powers have become increasingly strained. Therefore, it is in their best interest to utilize this new influence in the Shaam as a threat to American foreign authority and reduce the importance of an alliance with the United States in the MENA region. As the U.S. becomes less significant in these situations, new powers that may be enemy states will have more opportunities to damage U.S. national security through the development of new alliances and the extension of their sphere of influence.

There is also the matter of the escaped ISIS prisoners. The foreign fighters that have not been repatriated now have potentially unlimited contact with individuals in their home country, increasing domestic terrorist threats. The aforementioned concerns of re-escalation have been confirmed by reports of ISIS regrouping and continuing attacks. It has yet to be seen if the predicted inflows into Europe will occur, but the mass outbreak of ISIS prisoners has begun to affect the Sham region and has reduced trust in U.S. intentions and interests. Military presence has been maintained in Syrian oil fields, and American former ISIS members have remained in custody as informants. These actions have damaged American human rights and alliance records, ultimately reducing the stability of U.S. national security.

Potential Outcomes

Understanding the current standing of the U.S. in international relations emphasizes the importance of carefully shaping effective policy to address this issue. The FBI has identified 20 American foreign fighters, but government estimates places the total number of American jihadists abroad around 130. The risks that come with returning this population or denying them U.S. citizenship should be understood in the contexts of domestic safety and national security abroad. Both cases shall be presented through an analysis of current repatriation programs, public reactions, and alternative solutions.

The Case for Returns

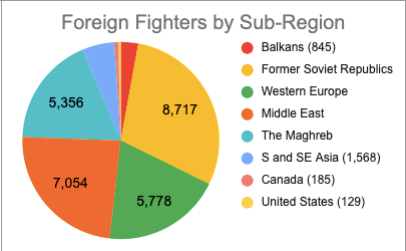

Data obtained from The Soufan Center 2017 Report. This graph compiles the government estimates of foreign fighters across major sub-regions; Canada and the U.S. are separated for the purpose of this paper.

When arguing the case for returning former fighters, it is more useful to analyze current state responses to former ISIS members seeking renationalization. This has largely occurred without any multilateral cooperation, with states enacting domestic policy on a case-by-case basis. The U.S. Justice Department has primarily negotiated plea deals with former ISIS members seeking repatriation or subjected captured fighters to fair and just trials. However, President Trump has also promised to utilize Guantanamo Bay, kept open indefinitely by E.O. 13492, to detain former ISIS fighters. This policy does not address the issue of women and children, who are a majority of the 20+ American members of ISIS identified by the FBI. The population of American ISIS fighters is scattered across Kurdish-operated prisons and Syrian refugee camps, meaning that the potential of continued radicalization increases as contact with jihadists continues. However, the U.S. and the North American region have significantly lower numbers of foreign fighters and more capabilities to address each case. Concerns about repatriation emerge from fears of re-radicalization and recruitment on domestic soil.

The successful return of former fighters relies entirely on the deradicalization efforts employed by their home state. Studies have found that radicalization tends to be more personal than ideological. As a result, ISIS recruiters would appeal to potential members based on their individual concerns and grievances. The RAND Corporation’s review of rehabilitation programs has found that the most successful apply this concept of an individualized approach to deradicalization and community integration. Notable successes include the Aarhus and Slotevaart deradicalization programs in Denmark and the Netherlands, respectively, as well as Sri Lanka’s and Somalia’s community-based repatriation programs. Repatriation of former fighters and continued deradicalization is possible with the creation of dedicated programs to facilitate the process. The question then becomes: are states even willing to accept returnees and fund rehabilitation programs?

The Case for De-Nationalization

Data obtained from The Soufan Center 2017 Report. The graph compares number of returnees to total foreign fighter estimates across regions and countries.

One of the arguments against accepting returning ISIS fighters is the failure of de-radicalization programs. Both England and France have less effective programs than the aforementioned European programs as a result of the comparatively higher rates of returnees. These states do not have the resources needed to operate individualized rehabilitation and have received major public backlash after it was revealed that taxpayer money would fund these programs. There is also the concern that even with effective de-radicalization processes, re-radicalization could occur. Scholars have identified positive correlations between local discrimination (i.e., xenophobia, Islamophobia, racism, etc.) and jihadist attitudes in minority communities. Therefore, the removal of any possibility of radicalization could require a mass decrease in prejudiced attitudes or the major resettlement of former fighters.

Overall, the process of identifying, evaluating, and potentially repatriating former jihadists is extremely difficult and contains many risks. The U.S. continues to have difficulties identifying citizens. A majority of foreign fighters burn their identification documents as a symbolic de-nationalizing process and therefore do not have any proof of American citizenship. Furthermore, some fighters take the Arabic translation of their nationality as their last name. While none of these cases have resulted in ISIS members passing U.S. borders, there have been cases of repatriated former jihadists committing terrorist attacks in both the United States and Europe. It must be noted that only one U.S. case was directly associated with a terrorist organization. However, not enough time has passed for states to evaluate any risk based on the currently returned former fighters.

States have instead been looking to end the problem by placing the responsibility outside of their borders. Some proposals include multilateral action through the creation of an international tribunal to evaluate individual returnee cases or through increased leadership from the International Criminal Court (ICC). Others advocate for bilateral action. Before the U.S. withdrawal from Syria, the most popular alternative was paying the Kurds to continue holding former fighters in prisons. The U.S., which has developed unfriendly rhetoric and policy around the subject, has also been ramping up pressure on European states to repatriate their former fighters.

Conclusion

The current U.S. policy governing the return of former ISIS members has followed a general trend of retracting from multilateralism and prioritizing defense interests. While the DOJ committed itself to trying to rehabilitate former jihadists, the Executive Office has emphasized the importance of imprisoning the population and preventing them from re-entering American borders. This occurred simultaneously with U.S. threats to diplomatic relations with allies and refocusing the role of the military in international conflicts. Future policy regarding ISIS returnees now must ensure domestic security and emphasize the importance of foreign relations to create a more well-rounded national security doctrine.

Policy Recommendations

Current U.S. policy on ISIS returnees falls under the “denaturalization” category. In mid-2018, the Trump administration extended the powers of the Obama-era Operation Janus through the creation of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services denaturalization task force. The task force began evaluating the citizenship of convicted former terrorists, specifically those still in custody, in 2019. This reveals two problems in the current U.S. returnee systems. First, it is biased towards natural-born U.S. citizens who often serve shorter times and are released without the necessary proof of deradicalization. Alternatively, naturalized citizens face unique threats to their citizenship status and rights (See: the cases of John Walker Lindh and Iyman Faris). This highlights the second weakness: the ineffectiveness of prison-based deradicalization systems. Imprisonment does not provide a positive alternative to the message of radicals and cannot properly identify any real change. The following policy proposals will provide improvements to both current returnee and denaturalization policies in the effort to increase the strength of U.S. national security.

Returns: Addressing the returns of former ISIS members has to happen in two stages. First, the seven returnees that the DOJ has tried should continue to receive prison-based deradicalization education. During the resettlement period, community-based rehabilitation programs should be enacted by the relevant government departments (e.g. DOS, DHS, DOJ, etc.) and the local populations. For the 20+ former members remaining in camps and prisons, the U.S. will have to continue to engage in bilateral efforts with the Kurdish fighters, the Turkish and Iraqi governments, and international non-governmental organizations to identify American citizens and facilitate their return. This population of returnees will then undergo the same system of a fair trial, continuous deradicalization, and resettlement.

De-Nationalization: Non-return policies will also require multi-lateral efforts and changes. Former ISIS members that lose their citizenship, including the former terrorists in custody that will be deported as a result of this policy, will have to be monitored. This will reduce opportunities for further radicalization or re-grouping of terrorist organizations. A multi-lateral coalition of fighter-source countries could also negotiate with regional governments or international organizations for the permanent holding of former ISIS members. The participation of the ICC and independent monitors would be necessary to ensure the protection of human rights and some civil liberties (e.g. due process, fair trial, etc.). If the U.S. government chooses to pursue de-nationalization policies, then it will also have to reduce the pressure on European countries to accept returnees.

Both policy paths would require improved U.S. relations with the Kurds and European governments, as well as increased participation in international agreements and organizations. Improving U.S. standing in global politics and extending American influence serve to increase national security through its diplomatic aspects. Reducing terrorist threats, whether through de-radicalization or various degrees of monitorization, protects domestic and international American populations. Properly addressing the issue of ISIS returnees has the potential to significantly improve U.S. national security by mending damaged relationships with allies, reducing domestic threats to safety, and further reducing the power of a global terrorist organization.