A nation must think before it acts.

This essay is based on the Third Annual Ginsburg-Satell Lecture on American Character and Identity delivered on June 17, 2020.

Seven years ago, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported proudly on the city’s 20th annual Welcome America! celebration. Its bold headline quoted Mayor Michael Nutter to the effect that “Philadelphia owns the Fourth of July.” What evidence exists to substantiate that boast? Was the Philadelphia Factor truly decisive to the American founding?

The Temptation to Prolepsis

In his 1997 History of the American People, Paul Johnson summarized some of the evidence as follows:

Amid this prosperous rural setting, it was natural for Philadelphia to become, in a very short time, the cultural capital of America. It can be argued, indeed, that Quaker Pennsylvania was the key state in American history. It was the last great flowering of Puritan political innovation, around its great city of brotherly love. . . . Its harbor at Philadelphia served as a national crossroads leading north, west, and south. . . . It became in time many things, which coexisted in harmony: the world centre of Quaker influence but a Presbyterian stronghold too, the national headquarters of American Baptists but a place where Catholics also . . . flourished, a center of Anglicanism but also a key location both for Lutherans and . . . many more German groups, such as Moravians and Mennonites. In due course it also housed the African Methodist Episcopal Church. . . . With all this, it was not surprising that Philadelphia was an early home of the printing press, adumbrating its role as the seat of the American Philosophical Society and birthplace of the Declaration of Independence.

Pennsylvania became known as the Keystone State even though it isn’t really a state, but one of the four Commonwealths along with Massachusetts, Virginia, and Kentucky. As early as 1803, the Jeffersonian journal Aurora published by Benjamin Franklin Bache dubbed Pennsylvania “the keystone in the democratic arch.” And ever since then, most historians have agreed that Pennsylvania occupied a key position among the colonies by virtue of its demography, geography, and economic, social, and political importance. They have argued or simply assumed that Philadelphia was no accident, but the sine qua non of the American Revolution.

But historians must always beware of prolepsis: the fallacy of interpreting the past in terms of an implicitly inevitable future; in short, to read history backwards. William Penn and Benjamin Franklin are cases in point because many eminent historians have heralded their tolerance, egalitarianism, industry, enlightenment, and capacity for self-reinvention as “proto-American” qualities, “For better or worse, rightly or wrongly,” wrote Charles Sanford, “Benjamin Franklin has been identified with the American national character. Though greater hero worship has been accorded to Washington and Lincoln, historians have almost unanimously judged Franklin to be more representative. He is the inventor of the American character and American way of life.”

Thomas Carlyle called Franklin the “father of all Yankees” and Paul Elmer More “America’s Renaissance Man.” Frederick Jackson Turner dubbed him “the first great American” and H. W. Brands “the first American”—period. To Walter Isaacson, he was “the multiple American”; to Jonathan Lyons “the Enlightened American”; to Gerardo Del Guercio “the inventor of the American Dream.”

All that amounts to prolepsis because it assumes the United States was already “out there” on the horizon in 1723 when Franklin left his native Boston for Philadelphia or even in 1682 when William Penn received his colonial charter. But in truth, Penn was an English imperial patriot who had no notion of planting the seeds of a new nation.

And Franklin—as last year’s Ginsburg-Satell Lecture clearly showed—was another British imperial patriot until, at age 68, he reluctantly embraced the American cause after suffering public humiliation by the king’s Privy Council. Indeed, very few of the Founding Fathers had any notion that they were about to establish a new nation. For instance, George Washington wrote in a letter (to Captain Robert Mackenzie) on October 9, 1774, just six months before Lexington and Concord: “I think I can announce it as a fact, that it is not the wish or interest of the Massachusetts government, or any other upon this continent, separately or collectively, to set up for independency … on the contrary, it is the ardent wish of the warmest advocates for liberty, that peace and tranquility, upon constitutional grounds, may be restored, and horrors of civil discord prevented.” Can it be that American independence was not an inevitability, but an improvisation?

Some Disturbing Counterfactuals

To be sure, the political consciousness of the colonists coalesced quickly during the decade after 1765, when the Stamp Act initiated the imperial crisis. But independence seemed the least likely outcome, so much so that contemporary observers regarded the unfolding events with shock, dismay, and disbelief. As recently as 1763, when the Seven Years War, or last French and Indian War, ended in Anglo-American victory, colonists had toasted the health of King George III with gusto. Just a dozen years later, the same colonists damned his eyes and reached for their muskets. And for what? The ostensible causes seemed wholly inadequate to explain the scale of the unfolding tragedy.

Joseph Galloway, Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly from 1766 to 1775, asked, “How then can it happen that a people so lately loyal, should so suddenly become universally disloyal, and firmly attached to republican Government, without any grievances or oppressions but those in anticipation?” Galloway hoped the discord had been exaggerated out of proportion, and that reconciliation might still be effected. So historians—far from taking the future for granted—ought to have asked what might have happened had the British been more forthcoming or the colonists less hot-headed? Surely secession and civil war—which is what the American Revolution amounted to—needed more of a cause than a three-penny tax on tea.

Schoolbooks have always taught American children that it was the principle of the thing: taxation without representation and the dangerous precedent of Parliamentary supremacy. That external excuse then became the ostensible justification because of the Americans’ decision to declare independence. Jefferson had to argue, out of a “decent respect to the opinions of mankind,” that the cause of the rupture was British oppression, hence his long bill of particulars. But implicit in that pretension was the counterfactual that the revolution would not have occurred if wiser policies had prevailed in London. Instead, the six lords who served King George as prime ministers during that decade only exacerbated the crisis: Grenville was too narrow-minded, Townshend too clever by half, Hillsborough too arrogant, Pitt too infirm, Dartmouth too weak, North too stubborn, and King George too solicitous of all the above. But to suggest that American independence was a by-product of botched British policy did not suit the needs of the emerging American civil religion, which required the national founding be not accidental but providential. So almost from the beginning historians began to interpret the birth of the United States as divine revelation, taught its values to the next generation, and implicitly recommended them to the whole human race.

A second set of counterfactuals suggests what might have happened had the colonists been less hot-headed, less jealous of their autonomy from crown and Parliament? After all, the conquest of Canada imposed new burdens, responsibilities, and costs on the British, which they naturally expected their North American colonies to share. Hence, the king’s Proclamation Line of 1763 prohibited new frontier settlements beyond the Appalachians out of deference to the Native Americans. The Quebec Act of 1774 established rather than abolished the Catholic Church in Canada out of deference to the Quebecois. The Sugar Act, Currency Act, Quartering Act, Stamp Act, Townshend Acts, and Tea Act were parliamentary attempts to pay down the national debt by raising revenue in the colonies. Of course, the angry colonists resisted, which provoked the Coercive Acts that Americans deemed Intolerable. Yet, all those measures, while necessary conditions, were still not sufficient to explain civil war and secession.

The sufficient cause could only be a new self-awareness, what John Adams called the revolution in men’s minds that had to precede the political acts of separation. And that occurred once those various provocations caused the colonists to inquire, for the first time, into the nature of the British Empire. The 13 colonies had all been created by private companies with royal charters wholly independent of Parliament. Hence, delegates to the First Continental Congress—even Quaker Accommodationists such as Joseph Galloway and John Dickinson—were convinced that Parliament had no right to legislate for the colonies whether or not it was a matter of “taxation without representation.”

In fact, Galloway proposed in September 1774 a constitutional plan for the empire providing for an American parliament to be chosen by the colonial assemblies and an American president-general to be appointed by the crown. But even the moderate First Continental Congress voted down “taxation with representation” by 6 colonies to 5. In January 1775, Lord North proposed that Parliament not legislate for the colonies, but simply request the colonial assemblies to decide for themselves how to contribute to administration and defense. Congress rejected that, too. Finally, Josiah Tucker, Dean of Gloucester, suggested Parliament call the colonists’ bluff and force independence upon them in the expectation they would come groveling back with an appeal to the crown. That proposal was never made, but it was certainly true that Americans’ anger was never directed at King George until Tom Paine wrote Common Sense in 1776. So the historian might well imagine a self-governing American Dominion under British sovereignty might have emerged from the crisis of the 1770s and might even survive to our day if not for some internal reasons why American Patriots would settle for nothing less than independence.

A third set of counterfactual “what ifs” may be drawn from the military history because the Americans’ Glorious Cause could easily have aborted on many occasions. What if the British had routed the Minutemen on Bunker Hill? What if Washington’s army had been trapped on Long Island instead of slipping to the mainland under cover of fog? What if the British captain who got Washington in his sights on the Brandywine had pulled the trigger? What if Washington had decided against marching his army 500 miles from New York in the slim hope of trapping Cornwallis at Yorktown? And so on.

Given all those contingencies, it would appear the birth of a United States of America was a fluke. And yet, the same historical narrative suggests that what made the glorious fluke possible was the location, culture, and people of Philadelphia. If Washington was the indispensable man, then Philadelphia was the indispensable city that made possible the Declaration of Independence, victory in the Revolutionary War, and the triumph of the Constitution. At least, that is what I hope to argue, beginning with some background on the unique colony founded on the Delaware River by Quakers.

The Quaker Colony … Not!

An historian recently prefaced his new biography with a lament. “When I ask my students in the US history survey who was William Penn, responses range from blank faces to the inevitable, ‘he’s the guy on the Quaker Oats box.’ Sadly, in 24 years of college teaching I have watched Penn and the Quakers slip ever deeper into the recesses of historical memory.”

That is a shame because Penn still casts a long shadow from his perch atop Philadelphia’s City Hall whence he gazes down on Penn’s Landing to welcome all newcomers. He was the son of the famous Admiral William Penn who captured Jamaica for Cromwell’s Commonwealth, but whose clandestine ties to the exiled Stuarts paid off when Charles II was restored in 1660. The king and his brother James, the Duke of York, promised the admiral upon his death in 1670 that they would look out for his son. But the son had improbably turned Quaker and thus pacifist, hostile to all authority, and egalitarian to the point of treason. Why did the king in 1681 grant Penn an exclusive charter to lands as extensive as England itself? Was it just to pay off a large gambling debt which Charles owed to the admiral’s estate? Or was it a ploy to lure Quakers out of the country? Or did Penn, who was already experienced in the colonization of New Jersey, know how to slip his petition past the Lords of Trade without notice? The likely answers are no, no, and no because whatever personal motives might have been involved, the creation of Pennsylvania was premeditated statecraft on the part of the Stuarts. First, a strong colony on the Delaware would swallow the Swedish and Dutch settlements already there and strengthen the English grip on the commerce of the entire American seaboard. Second, putting a proprietor in charge kept the colony off the government’s books. Third, awarding the province to Penn ensured a friendly, peaceable neighbor for New York, whose proprietor was his patron, the Duke of York (and future King James II).

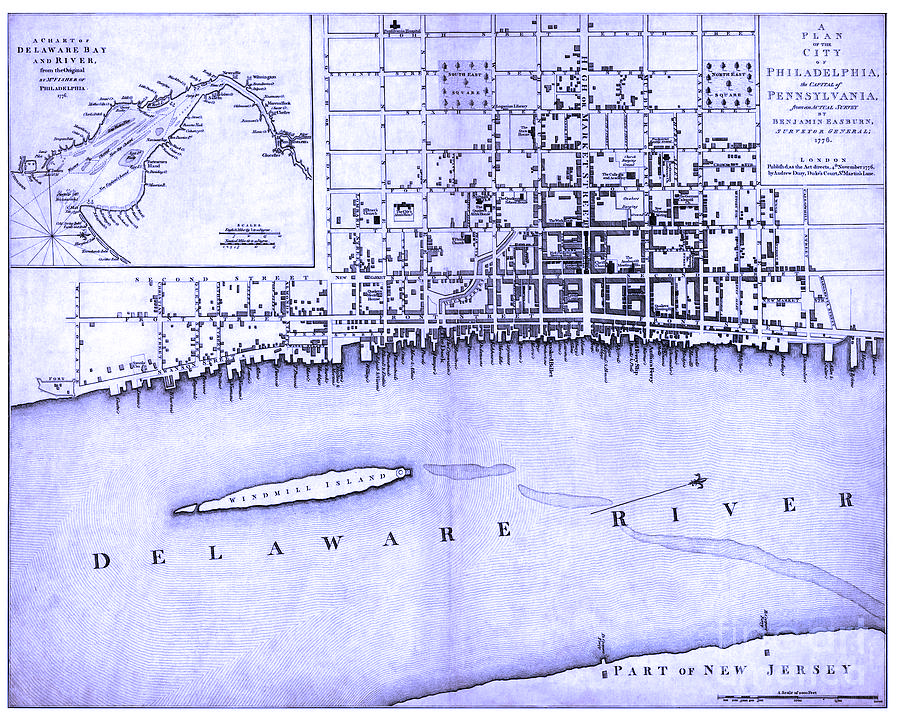

Penn attracted investments from wealthy Quaker merchants, one of whom was Thomas Holme who surveyed the rectangular grid of streets between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers where Penn imagined his City of Brotherly Love becoming a “green country town.” Penn sailed over in 1682 with an armada of eighteen large ships loaded with abundant supplies and the vanguard of 11,000 skilled settlers who emigrated during the first decade alone. Penn’s agents in Wales, Ireland, France, and the Rhineland aggressively marketed the fertile soil, water, a “sylvania” of timber, a “holy experiment” in religious tolerance and political liberty, and sold half a million acres the first year alone.

Penn was a disciple of political theorist Algernon Sidney, who believed that government should be free of coercion, ensure equal opportunity, and be blind to differences of birth, background, and faith. But the Frame of Government contained in Penn’s charter required that settlers give total obedience to the proprietor who in turn owed total obedience to the crown. Sidney was appalled: “The Turk is not more absolute,” he cried. What happened was that Penn bowed to the command of his friend, the Duke of York, who insisted on the same authoritarian arrangement drafted for Carolina by none other than John Locke.

Not surprisingly, Quaker settlers passively resisted Penn’s proprietorship in the name of his own principles. They scoffed at quit-rents and taxes, smuggled at will, and accused Penn of abandoning his colony even though he had to spend 15 years in England fighting various law suits. During those years, his friend the Duke had become King James II only to be deposed in Parliament’s Glorious Revolution of 1688. So Penn lost royal patronage. To make a long story short, in 1701, Penn was obliged to grant his colonists a new Charter of Privileges, which empowered their elected assembly to make its own laws and in fact exercise more freedom than any other in America, much to the frustration of James Logan whom Penn had left behind to manage the colony. The great seal of Philadelphia dates from this event, a shield depicting a handshake, sheaf of grain, scales of justice, and merchant ship. By then, Philadelphia was already America’s second city: a hustling port of 5,000 people who shipped flour, meat, and lumber to the West Indies and speculated on real estate. People even sub-migrated from other colonies because Pennsylvania quickly acquired a reputation as “the best poor man’s country.”

By then, the proprietor himself had been mugged by his own colonists, swindled by various business partners, suffered a stroke, gradually lost his memory and—despite being the biggest landlord in the Atlantic world—died in poverty in 1718. But he was not remembered as a tragic figure at all thanks to his magnificent legacy as lovingly described by biographer Mary Maples Dunn: “William Penn conceived of and actually established a tolerant, pacific society blessed with true freedom of religion, a criminal code humane beyond anything known in England, a written constitution, and a bill of rights. . . . Penn’s greatness was greater than the sum of his parts.”

Indeed, liberty and equality were more on display in Pennsylvania than anywhere else in America save, perhaps, quirky Rhode Island. But as Pennsylvanians became more diverse, they ceased to use their freedom to advance Quaker principles. To be sure, the Quaker party still clung to a slim majority in the Assembly during King George’s War (War of Austrian Succession), and refused to contribute to military defense from 1739-48. But the valleys west of Philadelphia were filling with Lutheran Germans, who in fact invented the famed Pennsylvania rifle, and Presbyterian Scots-Irish, who were downright belligerent. When a French sloop was sighted in Delaware Bay in 1747, the transplanted Bostonian Benjamin Franklin published Plain Truth, which argued against pacifism on Biblical and practical grounds, and Philadelphians responded by founding a militia association, symbolically ending the era of Quaker control.

Franklin’s Philadelphia

Franklin migrated to Philadelphia in 1723, settled there permanently in 1726, and set up as a printer in 1728. As we heard in last year’s lecture, Franklin both rode and drove the town’s prodigious growth, founding among other things its first fire and police patrols, lending library, college, philosophical society, post office, masonic lodge, and publishing industry. Meanwhile, the town’s population rose to 13,000 people by 1740, 20,000 by 1760 (thereby surpassing Boston), and nearly 40,000 by 1776. To be sure, that is only half the size of present-day Camden, but, in the 18th century, Philadelphia was the largest English-speaking city on earth save London. What is more, Penn’s “green country town” became highly urbanized because it was much cheaper to subdivide urban lots or build up rather than out. So Franklin’s Philadelphia reached inland only so far as 8th Street. Nevertheless, European visitors, of which at least 22 penned travelogues, wrote mostly glowing descriptions. Lord Adam Gordon thought it “one of the wonders of the world, if you consider its size, the number of inhabitants, the regularity of its streets . . . their spacious publick and private buildings, Quays, and Docks . . . one will not hesitate to Call it the first Town in America, but one that bids fair to rival almost any in Europe.”

Not surprisingly, the diversity, freedom, and close quarters made for contentious politics among pro- and anti-proprietary parties, the Quakers, Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Germans. Franklin was a party of one. He damned the “stiff rumped” Quakers, feared the swarming Germans, and had little use for the others. But he made friends in every camp and devoted himself to unity among the bickering factions in Pennsylvania, between Pennsylvania and the other colonies, and between America and Britain. A great exponent of Enlightenment reason often considered a Deist, Franklin even befriended the charismatic evangelist George Whitefield who made eight visits to Philadelphia during the religious revival historians call the Great Awakening. Its enthusiastic, evangelical, individualistic faith split every Protestant denomination and severed ties between Americans and European church authorities, thus helping to lay the basis for a revolutionary alliance between the Awakened and the Enlightened.

As Pennsylvania matured, it was said even of Quakers that the values of the counting house eclipsed those of the meeting house. But Philadelphians also combined their materialism with an idealism that never characterized New York, a toleration that never characterized New England, and egalitarianism that never characterized Virginia. Moreover, their ability to broadcast a diversity of opinion was as fecund as their freedom to do so because William Bradford’s first printing press dated from 1686, just three years after Philadelphia was founded (Boston, by comparison, waited eighteen years). Between 1740 and 1776, no less than 42 printers plied their trade in the city.

Most important—and contrary to Philadelphia’s image today—most of the city’s elite came from somewhere else: 30 percent from other colonies, and 25 percent from Europe. And since Quakers back then discouraged higher education, the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) founded by Whitefield and Franklin drew only 5 percent of its students between 1757 and 1800 from wealthy locals. Indeed, the WASP elite we associate with the city really dates from the post-Civil War industrial era, notwithstanding the reputation of Whartons, Mifflins, Rittenhouses, Biddles, and merchants like Robert Morris and Stephen Girard. The colonial city lacked what sociologists called a hegemonic or homogeneous elite such as prevailed in the plantation colonies, Hudson Valley, or Boston where just 4 percent of the wealthy were born abroad.

Finally, Philadelphia was better equipped than anywhere else in the colonies with boarding houses, taverns, and public buildings, especially the lavish State House designed by Andrew Hamilton and Edmund Wooley, where a sizeable convention could meet in relative comfort. If there was any location where disparate delegations might contrive to make “thirteen clocks strike as one” (in John Adams’s words), it was Philadelphia—except that Adams and other zealots from New England and Virginia still associated the city with Quaker passivity, so they came to the First Continental Congress in 1774 determined not to let the venue decide the outcome!

The Philadelphia Factor: Declaration of Independence

It seemed Adams had a point. Even after nine years of escalating tensions during which John Dickinson gained fame as the author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania—Penn’s colony still remained notorious for conservatism. In fact, Patriots from elsewhere were mistaken to think that Philadelphia’s culture a barrier to bold action. First, it was essential that Pennsylvania serve as anchor on the American ship of state so that when at last it did set sail all except diehard Tories were satisfied that the colonies had patiently and prudently gone the extra mile. That is, if even Philadelphia acquiesced in a declaration of independence, then a critical mass of Americans everywhere could be counted upon. Second, it turned out Adams was wrong about the temper of Philadelphia as a whole. It turned out the very hostility to authority and tradition, and openness to new people and ideas characteristic of Penn’s colony, created space for the popular faction to undertake revolutionary action despite the opposition of “stiff-rumped” Quakers in the Assembly.

The first inkling of that came in 1774 when the Boston Committee of Correspondence, desperate for support against the Intolerable Acts, sent Paul Revere on his first famous ride to beg Philadelphia merchants to join an embargo of British trade. He was welcomed by a mass rally at the City Tavern that attracted merchants, but scores of artisans and mechanics as well. They persuaded John Dickinson to draft an invitation to “a general Congress of Deputies from the different Colonies, clearly to state what we conceive our rights and to make claim or petition of them to his Majesty, in firm, but decent and dutiful terms.” Proprietor John Penn, who now served as governor, forbade the Assembly to participate, whereupon the popular party staged an extra-legal convention to choose delegates.[1] When the Congress convened in September, John Adams also persuaded it to spurn the Pennsylvania State House with its Quaker associations in favor of Carpenter’s Hall.

Back in 1765, a Stamp Act Congress had been held in New York. That befit the word’s eighteenth-century connotation of a body of representatives from separate polities coming together to concert their action for a specific purpose. The Philadelphia body was not really a “Congress” in that sense because it gradually assumed the powers of an ad hoc legislature. Indeed, this First Continental Congress, by denying Parliament’s right to legislate, rejecting the Galloway Plan, and urging the colonies to prepare for armed resistance, implied that its ultimate raison d’être was self-government.

The authors of a classic 1884 history of the city (which has pride of place in my library thanks to FPRI Chairman Robert Freedman) were not exaggerating when they claimed: “To write a complete history of Philadelphia during the war of American independence would be, in effect, to write the history of that revolution from its beginning until the adoption of the Constitution. . . . Philadelphia was the fulcrum which turned a long lever.” My contemporary colleague Michael Zuckerman adds that “Geography is only opportunity, not destiny” and that “the most intriguing issues . . . are issues of the conditions of creativity – political creativity, economic creativity, and especially cultural creativity – in the eighteenth-century city.” Philadelphia offered not only the locus and atmosphere, but a critical mass of leaders, including Charles Humphreys, Robert Morris, Charles Thomson, John Morton, James Wilson, and John Dickinson, many of whom were transplants to the city.

For instance, how many have heard of Charles Thomson, the eminence grise of the American Revolution? Born in Northern Ireland, he arrived in America an 11-year-old orphan in 1740 and seemed condemned to life as a blacksmith’s apprentice. But Charles ran away and got lucky. Charitable benefactors placed him in schools, first in Maryland and then Philadelphia, where he apprenticed in a merchant house, grew modestly rich, and married into the family that owned the Harriton Plantation in Lower Merion township. His first public service was in 1757 as shorthand recorder for the Quakers’ council with the famous Indian sachem Teedyuscung, who even gave Thomson a lifelong nickname, the Lenape word for “truth-teller.” During the crisis with Britain, John Adams gave him another: “the Sam Adams of Philadelphia.” In 1765 he served as Secretary to the Stamp Act Congress and then, beginning in 1774, Confidential Secretary of the Continental Congress, in which post Thomson quietly stage-managed American politics for the next 14 years! He corresponded with Jefferson, Washington, Franklin, and every member of Congress. He knew all their jealousies and ambitions, and where all the bodies were buried. He had personal charge of intelligence operations and ran networks of spies at home and abroad. Yet, Thomson somehow made no personal enemies at all because he was humble, devout, patriotic, and utterly scrupulous.

The Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, a month after fighting broke out on Lexington Green. But there was no assurance the other colonies would let the hothead New Englanders drag them into treason and war. But a sea-change occurred in Philadelphia, where the formation of extralegal committees to bypass the proprietor’s assembly had quickly become a habit. As one historian put it, Pennsylvania in Spring 1774 was still governed by an oligarchy based on a restricted electorate, but in just two years turned into the most vibrant participatory democracy in the world. This radical, militant populism was the basis for historian Carl Becker’s claim that the American revolution was not about “home rule, but about who would rule at home,” a claim later revived by Marxist historian Gary Nash. But the important point is that Patriots in Congress were greatly encouraged by what was happening in Philadelphia’s streets.

The populist movement climaxed in the formation of militia committees that made the willingness to bear arms the measure of patriotism, in defiance of the wealthy Quakers (still 15 percent of the city’s population). Thousands of militiamen marched, drilled, and in effect governed in defiance of the Assembly, psychologically preparing a critical mass of the populace and the Congress for armed resistance.

Accordingly, the Second Continental Congress began to function as an American government even before it declared independence.[2] On June 14, 1775, it founded the Continental Army and overcome sectional rivalries by naming Washington its commander. John Adams was the wise head who nominated the “gentleman from Virginia” and thereby cemented an alliance between New England and the South. But it is hard to imagine his unanimous selection had Congress met anywhere else but on Philadelphia’s neutral ground. October 13, 1775, was the birthday of the United States Navy and November 10 that of the U.S. Marine Corps. Still, opinions were sharply divided over the prospect of independence, which Pennsylvania delegates Dickinson, his legal protégé James Wilson, and businessman Robert Morris considered risky and at best premature. So Congress decided to send Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania’s agent in London, an “Olive Branch Petition” to present to the king even as it also approved a plan to invade Canada 13 months before the Declaration of Independence.

Finally, in November 1775, another sojourner who had sailed for America on the advice of Benjamin Franklin and wrote a pamphlet that inflamed the colonies thanks to Franklin’s postal service. Tom Paine’s Common Sense evangelized the colonies with the republican gospel whose reception emboldened Virginia Congressman Richard Henry Lee to call the question on June 3, 1776. “Our enemies,” he cried, “are determined upon the absolute conquest and sub-duction of North America. It is not choice then but necessity that calls for Independence, as the only means by which foreign Alliances can be obtained; and a proper Confederation by which internal peace and union can be secured.” Eleven days later, those extra-legal militias surrounded the State House and goaded the Assembly into resolving in favor of “forming further compacts between the united colonies, concluding such treaties with foreign kingdoms and States, and in adopting such other measures as . . . shall be judged necessary for promoting the liberty, safety, and interests of America.”

Lee’s motion was hotly debated until July 1, when it was brought to a vote. Nine colonies voted aye, but New York’s delegation, pleading no instructions, abstained, Delaware divided 1-1 because Patriot Caesar Rodney was absent, and South Carolina and Pennsylvania split narrowly against.[3] The tension was electric because the British were on the verge of invading New York. Hundreds of sails had already been sighted off Long Island. Was this the best time to vote independence, or the worst? If the Pennsylvania delegation continued to hang back, chances were Delaware, New Jersey, and New York would as well, and the edifice collapse for want of its keystone.

Then something happened historians to this day cannot fully explain. When a second vote was called on July 2, Morris and Dickinson retreated “behind the bar” and sat with the gallery, recusing themselves. That left Pennsylvania’s decision up to Franklin and Morton, who were in favor; Willing and Humphreys, who were opposed; and James Wilson, who reluctantly broke with his mentor Dickinson and cast the decisive vote for independence. He did so, he said, because the people of Philadelphia had made their will clear in the “recent dramatic events.” As for Morris, he explained that while he still hoped for negotiations he refused to break the unity on which the colonies’ leverage depended. Morris later signed the Declaration. Dickinson never did, even though he knew it would turn his popularity into calumny. “I have so much of the spirit of Martyrdom in me, that I have been conscientiously compelled to endure in my political Capacity the Fires & Faggots of persecution.”

New York still abstained, but when the Delaware and South Carolina delegations fell into line, Congress pronounced the Declaration unanimous.

On July 3, Philadelphia’s militia committee chose its own slate of revolutionaries for Pennsylvania’s constitutional convention.[4] On July 4, Congress approved Jefferson’s redacted draft. On July 6, crowds of Philadelphians tore the royal coat of arms from the State House facade.

Historians Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh summed up the unique metamorphosis of the city. “Between 1760 and 1775 Philadelphia came of age and was now spiritually prepared to go its way alone. Silently and for the most part unconsciously, it had undergone an intellectual revolution; it had shaken off its early allegiance to Old World standards and conventions and had chosen for itself the democratic direction. . . . This process, effected in the short span of thirty-five years by hundreds of eager, able, intelligent Philadelphians, produced upon the banks of the Delaware a city owning the first broadly democratic society of modern times.”

The Philadelphia Factor: Wartime Diplomacy and Finance

To suggest the Philadelphia factor was equally indispensable to the outcome of the War of Independence would be a stretch. Even British occupation of the city in 1777-78 (during which Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania, and Washington’s army shivered at Valley Forge) had no strategic impact. But two Philadelphians, Franklin and Morris, played indispensable roles as chief diplomat and chief financier of the American cause.

David Hackett Fischer’s encyclopedic history Albion’s Seed, described the four cradle cultures British colonists planted in North America: the Puritans of New England; the Quakers of the Delaware Valley; the Cavaliers of the Chesapeake; and the Scots-Irish Bordermen of the Allegheny frontier. Fischer also imagined the War of Independence a sequence of conflicts fought by the four cultures. Phase one was the Puritans’ War waged by New England militias egged on by their Congregational clergy. Phase two was the Cavaliers’ War in which regular armies led by gentlemen fought conventional battles. Phase three was the Bordermen’s War waged by bush-wacking partisans in the southern back-country. Phase four was, if not the Quakers’ war (which would be a contradiction in terms), then a political struggle waged by civilians from the Middle Colonies.

In fact, all four phases occurred simultaneously, and success depended on all of them, not least the civilians’ war. Indeed, the most decisive event in the eight year conflict occurred in late March 1778 when King Louis XVI of France received Franklin at Versailles and concluded a full-fledged military alliance with the United States.

Recall the main purpose of the Declaration of Independence was to enable Congress to solicit foreign assistance. In other words, it was a war measure.

For as early as November 1775, Congress had named a Secret Committee of Correspondence to seek ties with foreign powers, and after the Fourth of July, 1776, the committee persuaded the 70-year old Franklin to head the American delegation. He had served as the colony’s agent in London for 20-odd years and was also well known in Paris as a scientist, statesman, philosopher, and rustic wit: roles he now reprised to perfection. His European experience had taught him the Machiavellian lesson that the sure way to fail in politics and diplomacy was to be forthright, direct, and impatient, whereas the deception, indirection, and patience at least gave a chance of success. Congress knew none of that when it asked John Adams to draft the so-called Model Treaty of 1776, a simple pact of friendship and commerce, expecting that was enough to win foreign recognition. Franklin did not waste the time of French Foreign Minister Vergennes with such displays of American idealism. Instead, he wooed and tempted the French while engaging in duplicitous correspondence designed to confound British spies, and assisting American spy Silas Deane to ship clandestine cargoes of French weapons to Washington’s army. But most of all, he waited, hoping for some big battlefield victory that would persuade King Louis that the American cause was for real. The Battle of Saratoga achieved that goal, and, on February 6, 1778, Franklin concluded a military alliance with Bourbon France, later joined by Bourbon Spain, and solemnly pledged to make war and peace together.

How critical were those alliances to American victory? Suffice to say that Washington won the climactic 1781 battle of Yorktown thanks to a French army commanded by Rochambeau, a Franco-American army commanded by Lafayette, a French fleet commanded by Admiral de Grasse, and a campaign plan drafted by Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, the Spanish commander in Havana.

Of course, the French crown did not wage war for a revolutionary republic out of ideological affinity. It waged war to avenge the prior defeat, disrupt the British Empire, and perhaps regain some colonies. Moreover, the French showed signs of wanting to make the United States a client and restrict its territorial growth. That is why when the British suggested peace talks after Yorktown, Franklin double-crossed Vergennes and negotiated separately with the British. John Jay and John Adams, whom Congress appointed to the peace delegation, were shocked and confused by Franklin’s duplicity. But they were happy to share the credit for the generous terms Franklin obtained in the Peace of Paris of September 3, 1783 (the real, international, birthday of the United States). “We were better diplomats than we imagined,” boasted Adams in retrospect.

What most textbooks do not tell you is that arms alone cannot win wars and that wars rarely pay for themselves. In 1781, the year Franco-American arms triumphed at Yorktown, Congress was broke and in fact $25 million in debt. But that was the moment Robert Morris placed his personal fortune at the disposal of the new nation. A grateful Congress broke its own habit of working through committees when it created an executive office for Morris, Superintendent of Finance, which he held for the duration.

Morris would later be accused of wielding dictatorial powers, lining his own pockets while posing as patriot, and indulging the reckless greed that in 1798 would consign him to debtor’s prison. What Morris really displayed, however, was the American penchant for hustling and creative corruption in the public interest. More than anyone else, he deserved the sobriquet “financier of the Revolution.”

He was raised in Liverpool, England, to age 13 at which point his father set up as a tobacco broker in Maryland. He sent young Robert to apprentice in Thomas Willing’s Philadelphia merchant house, where he made partner at age 20 and went on to make fortunes in commerce with the West Indies, Mediterranean, and India, not to mention slaving and opium. In 1776, he doubted the wisdom of declaring independence, but once it was done, he threw himself into the cause. “I am not one of those politicians that run testy when my own plans are not adopted,” he said. “I think it is the duty of a good citizen to follow when he cannot lead.”

So in 1776 and 1777, Morris exhorted Philadelphia businessmen to purchase supplies for Washington’s troops, and issued “Morris notes” backed by his own money. In the new state assembly, he worked to establish checks and balances and overturn religious tests for office, which Presbyterians had imposed to exclude Quakers, Mennonites, and Jews. He also assisted James Wilson in the legal defense of Haym Solomon, a patriotic financier also accused of profiteering.

His contributions climaxed in 1781 when, as U.S. Superintendent of Finance, he underwrote General Washington’s Yorktown campaign. The British did not yet despair, believing the war of bullets would now turn into a war of bottom lines that the United States was bound to lose. But thanks to Morris’s Bank of North America, the Congress and Continental Army staggered to the finish line.

Of course, American financial woes were far from over, as proven by the 1783 Newburgh Conspiracy. Officers led by General Alexander McDougall threatened to march their soldiers on Philadelphia if Congress did not guarantee their pay and pensions. General Washington’s authority and eloquence ended the revolt, but imagine if it happened while the war was still in doubt? Suffice to say, Washington became a close friend of Morris and indeed was his house guest from May to September 1787.

The Philadelphia Factor: Constitutional Convention

Those were the months when the Constitutional Convention designed a United States government, working what author Catherine Drinker Brown famously called “The Miracle at Philadelphia.” But this time, the venue was not a sure thing. In June 1783, two months after Newburgh, a contingent of soldiers did march on Congress and the Philadelphia city council dared not call up its local militiamen for fear they would only join the insurgents. So Congress, damning the “unhealthful & dangerous atmosphere” created by the city’s mob rule and corrupt elites alike, departed for Princeton and then for New York. Philadelphians, having hosted the Congress for nine years, bade good riddance to an institution which Dr. Benjamin Rush recorded, had come to be “abused, laughed at, pitied & cursed in every Company.”

Indeed, after the war, Congress just atrophied under the Articles of Confederation to the point where it often failed to attract a quorum. As New York’s socialite Eliza House Trist quipped in 1786: “Every now and then we hear of some Honorable Member getting a wife – else we should not know there exists such a Body as Congress.” It became painfully clear how badly the new nation needed an executive branch to oversee commerce, defense, and foreign affairs. That is why the Annapolis Convention of 1786, where five states sent delegations to discuss standardizing their commercial laws, called for a national convention “on the second of May next” to revise the Articles of Confederation. Needless to say, they chose Philadelphia again. But did that really matter? I put that question to my late colleague Richard Beeman, author of a book on the Constitutional Convention, who replied: “I believe that with the rule of secrecy being so faithfully observed by the delegates, they could have been meeting in a barn in western Georgia and the outcome might well have been the same. On the other hand, if the convention were held in western Georgia it probably would have attracted only a handful of delegates.”

Perhaps. But one cannot but think it mattered a great deal that the convention was held in Philadelphia, where independence had been declared and the new nation forged. All the features that had favored the city in 1774 applied even more 13 years later. Its population was 60 percent larger than New York’s and just as cosmopolitan. Its docks were loaded with goods from all over the world. Indeed, Morris and the French-born Philadelphia merchant Stephen Girard had just initiated America’s China trade. The city’s well-earned reputation for enlightenment was further enhanced by the Repository for Natural Curiosities, otherwise known as Peale’s Museum. Another native of Maryland, Charles Willson Peale at age 25 was attracted to Philadelphia precisely because of its revolutionary politics. But he went on to national fame as an artist (including no less than five portraits of Washington), scientist, inventor, and entrepreneur. All the convention’s delegates visited his museum described by a European philosopher as a “Temple of God! Here is nothing but Truth and Reason!”

Almost all historians concur that Philadelphia’s atmospherics deserve much of the credit for inspiring what Beeman called the “plain, honest men” in 1787. Convention delegates roomed, dined, and drank together at the City Tavern, Indian Queen, and London Coffee House. They exchanged ideas and opinions, fears and doubts at the bi-weekly market fairs on Front Street. Together, they endured the stench of the butchers and tanners, open sewage, pestiferous flies, and oppressive summer heat. They strolled through gardens graced with hummingbirds by day and fireflies by night. Perhaps that helps to explain how 39 (at least) of the 55 delegates crafted an entirely new frame of government in just four months’ time. And not least influential was the extraordinary Pennsylvania delegation itself.[5]

James Wilson, my personal favorite Founder, remains inexplicably obscure to this day. The brilliant Scotsman emigrated to Philadelphia at age 24 and quickly built a successful law practice. He represented Pennsylvania in both Continental Congresses and cast the decisive vote for independence. But in 1778, an angry mob laid siege to Wilson’s townhouse because he dared to defend some 23 wealthy residents suspected of collaborating with the British occupation. In the 1790s, he would become the University of Pennsylvania’s first professor of law and one of the first Supreme Court justices appointed by President Washington. But Wilson’s most lasting contributions were made at the Constitutional Convention, where he argued for “a republic or democracy, where the people at large retain the supreme power,” advocated popular election of the House and Senate, and proposed the three-fifths compromise on Congressional representation between the northern and southern states. He argued strenuously on behalf of a single executive and did more than anyone else to inspire the clauses defining the office of president.

Pennsylvania delegate Robert Morris nominated Washington to chair the Convention, then worked behind the scenes to ensure that the clauses on taxation and commerce were flexible and confined to “essential principles only.” He recommended that Pennsylvanians choose Gouverneur Morris, the elegant wordsmith responsible for the style and brevity of the Constitution. Pennsylvania delegate Benjamin Franklin, now 81, performed his final service as a member of the ad hoc committee appointed to break the deadlock between large and small states. Franklin’s endorsement of the so-called Connecticut Plan for equal representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House of Representatives proved decisive. And the reason the plan proved decisive was because the crucial swing vote was cast by delegates from North Carolina, which had previously voted with the other large states. And the reason the Tarheels changed their mind was because their most eloquent delegate was Dr. Hugh Williamson, a protégé of Benjamin Franklin who grew in Chester, Pennsylvania, studied medicine at the College of Philadelphia, and served as North Carolina’s state surgeon during the war.

Finally, no one understood better than James Wilson how vital it was that the Constitution be ratified in a timely manner and without amendment. So he proposed rules whereby states would vote in special conventions and only nine ratifications were required. Wilson left nothing to chance. On September 18, 1787, just one day after the signing of the Constitution, Federalists in the Pennsylvania assembly moved to stage a convention just two months hence. But the assembly was short of a quorum, so sergeants-at-arms were ordered to find two absent assemblymen—who happened to be anti-Federalists—and drag them to the State House so the guffawing majority could get its way. Over the next 60 days, Wilson conducted an intensive campaign of public relations and was rewarded when the Pennsylvania convention ratified the Constitution by a vote of 46 to 23. In fact, Delaware had done so six days earlier, hence its claim to be “the first state.” But Pennsylvania created the big-state momentum that soon carried Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia. So yet again, the United States of America was in good part a product of Philadelphia.

Providential After All?

Remember Charles Thomson, Secretary to the Continental Congress, spy master, and eminence grise of the American Revolution? Legend has it that he exchanged letters with President Washington in the 1790s about writing their memoirs since no one knew better than they what really had happened throughout the Founding Era. Washington dismissed the idea because he did not wish to lie to the American people nor disillusion them with the truth. He suggested instead that they humbly give the credit to Providence. Evidently, Thomson agreed. He burned his secret archives and devoted the rest of his life to a new translation of the Hebrew Bible.

So, does Philadelphia own the Fourth of July?

It certainly did on July 4, 1788, when the city celebrated ratification of the Constitution by the ninth state, New Hampshire. The festivities began at sunrise when church bells rang out and the Liberty Bell pealed in reply. Then, gunships on the Delaware River fired salutes as 5,000 people representing the arts, sciences, trades, escorted by the resplendent First City Troop, formed a parade that stretched one and half miles from Penn’s Landing to a country estate at Bush Hill at what is now 17th Street and Spring Garden. The pièce de résistance was Charles Willson Peale’s Grand Federal Edifice, an allegory of the U.S. Constitution. James Wilson delivered a victory speech after which the throng repaired to a giant circle of tables groaning with refreshments. Francis Hopkinson, the master of ceremonies who designed the flag sewn by Betsy Ross, had proudly decreed that no imported wines or spirits be served; only good American porter, beer, and hard cider.

Hopkinson was another Philadelphia polymath also renowned as a statesman, lawyer, artist, composer, inventor, and poet who wrote this ode for the day, likening the Constitution to an elegant garment:

Oh! For a muse of fire to mount the skies,

And to a listening world proclaim:

Behold! Behold an empire rise!

…….

My sons for freedom fought, nor fought in vain,

But found a naked goddess was their gain;

Good government alone can show the maid

In robes of social happiness arrayed.

Hail to the Festival! All hail the day!

Columbia’s standard on her roof display!

And let the people’s motto ever be,

United thus, and, thus united, free!

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

Selected Bibliography

Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1958).

Digby Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. New York: Free Press, 1979.

Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. New York: Random House, 2009.

Richard Beeman, Our Lives, Our Fortunes, and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776. New York: Basic Books, 2013.

Catharine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787. Boston: Little, Brown, 1966.

W. Brands, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. New York: Doubleday, 2000.

Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Rebels and Gentlemen: Philadelphia in the Age of Franklin. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1942.

Vincent Buranelli, The King & the Quaker: A Study of William Penn and James II. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, 1962.

J. C. D. Clark, “British America: What If There Had Been No American Revolution?” in Niall Ferguson, ed., Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals. New York: Basic Books, 1999, pp. 125-74.

Thomas M. Doerflinger, A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise: Merchants and Economic Development in Revolutionary Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1986).

Richard S. Dunn & Mary Maples Dunn, eds., The World of William Penn. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1986.

Harold D. Eberlein and Cortlandt V. Hubbard, Diary of Independence Hall (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1948).

Thomas Fleming, “Unlikely Victory: Thirteen Ways the Americans Could Have Lost the Revolution,” in Robert Cowley, ed., What If? The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1999, pp. 155-86.

Catherine E. Hutchins, ed., Shaping a National Culture: The Philadelphia Experience, 1750-1800. Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1994.

Benjamin H. Irvin, “The Streets of Philadelphia: Crowds, Congress, and the Political Culture of Revolution, 1774-1783,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 129, no. 1 (Jan., 2005), pp. 7-44.

Paul Johnson, A History of the American People. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776. New York: Vintage Books, 1972.

Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Knopf, 1997.

Jack Marietta, The Reformation of American Quakerism, 1748-1783 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1984).

Walter A. McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History 1585-1829. New York: HarperCollins, 2004.

John A. Moretta, William Penn and the Quaker Legacy. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

Gary B. Nash, Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1681-1726. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University, 1968.

Gary B. Nash, First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2002.

Gary Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking, 2005.

Gary B. Nash, The Liberty Bell. New Haven, Ct.: Yale University, 2010.

Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress. New York: Knopf, 1979.

Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Richard Alan Ryerson, The Revolution is Now Begun: The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765-1776. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1978.

Charles L. Sanford, ed., Benjamin Franklin and the American Character. Boston: D.C. Heath, 1955.

Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia 1609-1884, 2 vols. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, 1884.

Gordon S. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin. New York: Penguin Press, 2004.

[1] The Pennsylvania Delegation included: Joseph Galloway: native of Maryland, moved at 18; Charles Humphreys: Haverford native; Samuel Rhoads: Philadelphia native; John Dickinson: Wilmington native; Edward Biddle: Philadelphia native; Thomas Mifflin: Philadelphia native; John Morton: Ridley native; George Ross: New Castle native.

[2] The Pennsylvania Delegation included: Andrew Allen: Philadelphia native; George Clymer: Philadelphia native; John Dickinson: Wilmington native; Benjamin Franklin: Boston; Robert Morris: England, then Maryland; Benjamin Rush: Philadelphia native; James Smith: Ireland, but Philadelphia by age 2; George Tayleor: Ireland, moved age 20; Thomas Willing: Philadelphia native; James Wilson: Scotland.

[3] The Pennsylvania delegates John Dickinson, Robert Morris, Thomas Willing, and Charles Humphreys were opposed; Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, and James Wilson in favor.

[4] The Pennsylvania slate included Benjamin Franklin, David Rittenhouse, George Clymer, Owen Biddle, Timothy Matlack, James Cannon, and the zealous Germans Frederick Kuhl and Georg Schlosser.

[5] The Pennsylvania delegates were George Clymer, a Philadelphia native; Thomas Fitzsimmons, born in Ireland; Benjamin Franklin, born in Boston; Jared Ingersoll, born in New Haven; Thomas Mifflin, a Philadelphia native; Gouverneur Morris, born in New York; Robert Morris, born in England; and James Wilson, born in Scotland.