A nation must think before it acts.

Editor’s note: Arthur Waldron, writing in Orbis in spring 2019, offered his “Reflections on China’s Need for a ‘Chinese World Order.”’ This essay from Shay Stautz examines how those aspirations have fared in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The biggest annual legislative meeting in China began on March 4th amidst the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Notably, the focus of the weeklong meetings of the PRC’s National People’s Congress and the People’s Political Consultative Conference is the PRC’s economic growth targets. This seems out of focus given the largest armed conflict in Europe since World War II, yet it highlights that China is playing nearly no role in it.

This stands in stark contrast to the United States and its NATO allies, who have remarkably—but responsibly—walked the delicate line of supporting democratic Ukraine’s resistance to the brutal Russian invasion without triggering a broader Russian response against the alliance.

America’s leadership of NATO for the past seventy years, during past and the current crises, demonstrates the key aspect of global leadership—broad alliances built on common values. In contrast, the conspicuous absence of China’s influence over the invasion of Ukraine suggests the PRC’s inability to fulfill its oft-stated ambition to overtake America as the leader of the international system.

The United States Continues to Demonstrate What It Means to Lead the International System

NATO’s response to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has been unprecedented. By all accounts, Russia holds overwhelming advantages over Ukraine—ten times the military budget, absolute bomber and naval superiority (not to mention nuclear), ten times the number of fighter aircraft, and fifteen times the number of military helicopters, just to name a few. Ukraine’s military budget is reportedly less than that of city-state Singapore’s, but it has managed to counter or bog down Russia’s vaunted combined-arms maneuver tactics, maskirovka techniques, and cyber capabilities—and even Russia’s elite Spetsnaz special forces. In the first eleven days of the invasion, Russia has failed to establish air superiority, eliminate Ukrainian combat air support or Ukrainian anti-air capability, or use its vaunted offensive cyberwar capability to bring down Ukrainian command and control.

These issues have not yet been resolved—more than a week and a half into the invasion—and they are complicated by Russian struggles with logistics and sustainment, with armor columns running out of fuel. At the same time, twenty-plus countries, led by the United States and mostly NATO members, are rushing arms to Ukraine, with an emphasis on anti-air and anti-armor systems. Even Germany—which has historical reasons not to transfer weaponry—and technically neutral nations such as Sweden and Finland are shipping arms to Ukraine. This substantially complicates Russia’s plans for an easy victory and demonstrates just one reason why NATO is often described as the most successful alliance in history. As Putin gets bogged down in Ukraine, nations like Egypt, Turkey, and India will re-think their attraction to cheap Russian armaments and recent distancing from the U.S.

In addition to supporting Ukraine with military capabilities, the U.S., its NATO allies, and other democratic nations have also imposed precedented global economic sanctions on Russia. This includes Japan, South Korea, and even notoriously neutral nations like Switzerland and Sweden. In addition to freezing nearly half of Russia’s total international currency reserves, the U.S. and its allies invoked a “super sanction”—banning seven key Russian banks from access to SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication). SWIFT, based in Belgium, connects 200 economies through the rapid financial flows that make modern economies run. Putin gambled that the U.S. and its allies wouldn’t pull this trigger, but he clearly miscalculated. America explored engaging SWIFT for sanctioning Iran and North Korea during the global war on terror, as described in Juan Zarate’s 2013 Treasury’s War.

America’s leadership of NATO and engagement with the EU and with SWIFT is proving decisive in this crisis—JP Morgan is predicting an 11 percent drop in Russia’s GDP, similar to its plunge during the 1998 debt crisis. Russia is often described as a “gas station economy” for its dependence on exports of fossil fuels and minerals for nearly 50 percent of its annual federal budget. In fact, the limits of Russia’s economy may be one of the reasons for this invasion—Vladimir Putin knows that a Russia in demographic collapse and with an inability to innovate will not be a major part of the future global economy (for more on this, see Michael Beckley’s 2018 Unrivalled). These unprecedented sanctions—a combined effort of nearly two dozen major democratic nations—is possible only because of the international institutions that the United States has built based on common values, including NATO, over the last seventy years.

Another notable aspect of the international system’s response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is the emergency session vote in the General Assembly of the United Nations on March 2nd to condemn Russia. The last time the UN Security Council convened an emergency session of the General Assembly was in 1982—but this time, 141 member nations voted to condemn. In a forum where the United States is often voted against, only Russia, Belarus, Eritrea, North Korea, and Syria voted against the condemnation, while China and thirty-four other nations abstained—in effect supporting an autocratic, aggressive Russia.

The PRC May Aspire to Lead, but It Can’t When It Allies Itself with Autocracies

China’s long-established ambition to replace America as the leader of the global system are well documented. In his outstanding 2021 book The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, Rush Doshi meticulously documented the PRC’s numerous official aspirations for attaining global leadership. Viewed in this context, many have rightly observed that the PRC is closely watching America’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—but we must in turn observe the PRC’s response and note its relative imperceptible impact.

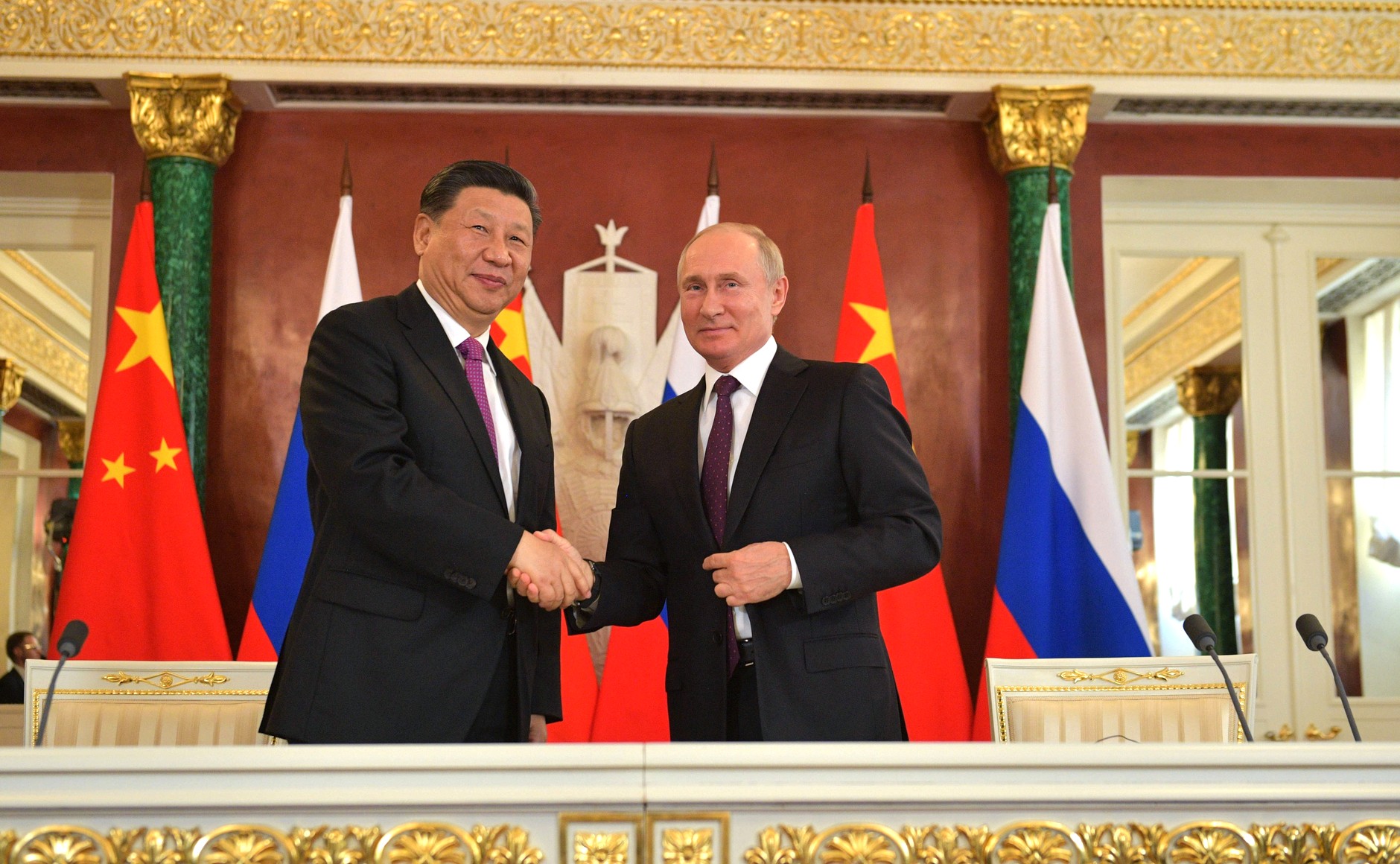

The fact that it abstained from voting on the UN resolution only thinly disguises its affinity with autocratic Russia—aligning itself with only thirty-nine nations in the vote. China’s aspirations for international credibility and influence aren’t helped by its increasingly close relationship with Russia’s Putin. In a communique before the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, Putin and President Xi vowed to “strongly support each other” and described their “no limits partnership.” Western intelligence services say that senior Chinese officials knew of Putin’s plans for Ukraine and asked Putin to delay his invasion until after the February 20th conclusion of Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympics. If true, this singular self-serving request is not an example of responsible international leadership—and so far it appears to be the sole example of any PRC ability to otherwise influence the crisis. The PRC publicly supported Russia’s buildup leading up to its invasion, abstained in the UN, and joined Russia in blaming the West for the conflict. One can conclude this is because Russia and China share common values, including an enmity to the democratic and individualistic values of the West, led by the United States.

The invasion of Ukraine has highlighted another dramatic weakness in the PRC’s bid to replace American global leadership: its lack of alliances. In contrast to the United States, which has alliances with more than fifty nations globally, China has alliances only with a few autocratic nations, none with particularly spectacular futures. This diminutive list includes North Korea, Pakistan, and—depending on circumstances—Myanmar and Russia. In view of America’s string of military bases worldwide, the PRC has learned from the U.S. the value of international alliances, of growing China’s influence in international organizations, and building relationships with nations globally. This can be seen in their Belt and Road Initiative to link Asian economies together through infrastructure, as well as creating previously unneeded financial institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, all in an effort to recreate the American global institutional framework built up since World War II—but in a Chinese-centric format.

Many have also commented on China’s close observance of America’s response to Ukraine to see if it presents an opportunity for it to move against Taiwan while the U.S. is distracted. This is a serious concern, and the U.S. is taking action to deter this—ranging from sending a delegation of former top-level U.S. national security leaders to Taipei to emphasize our democracy-to-democracy relations, as well as military exercises like the “elephant walk” of twenty-four F-15s in Japan on March 2nd.

Beyond our shared values with Taiwan’s 23 million people, the U.S. also has enormous strategic reasons for deterring a PRC attack on Taiwan, including its anchoring the “first island chain” of defense of the Pacific as well as its dominant role in manufacturing advanced semiconductors that the U.S. relies on. While the PRC has invested deeply in the capabilities necessary to conquer Taiwan, it remains a hard target, as described in Ian Easton’s 2019 The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia. The DoD estimates the PRC could be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027, and testimony in front of Congress by Taiwan’s defense minister in October 2021 suggested this could be as soon as 2025.

Should China choose to invade Taiwan, they now know for that full-blown SWIFT sanctions are in the Western playbook, and such sanctions would hurt China much more than they are affecting the Russians. It should also be noted that, like the Ukrainians, the Taiwanese have a strong and proud spirit of independence, and they will be inspired by the Ukrainian resistance to what was supposed to be an overwhelming power right next door. Furthermore, for Chinese military leaders who are counting on Russian S-300 and S-400 anti-aircraft systems and large numbers of advanced Russian SU-35 variants to establish air control over Taiwan, the Russian experience in Ukraine must come as a very unpleasant surprise.

In conclusion, China has watched from the other side of Asia as its Russian ally’s clumsy invasion of Ukraine is bogging down. But it should really be struck by how little it can affect how events unfold there. The Ukraine crisis demonstrates that China’s true inclination is to align with nations like itself—anti-Western, anti-democracy, and embracing of aggression—to the detriment of its future hopes to lead the international system. That dynamic prevents it from being able to assemble a broad coalition of nations with common values, and it ultimately means that it cannot lead in a world that has experienced the enlightenment of an American-led international order.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.