A nation must think before it acts.

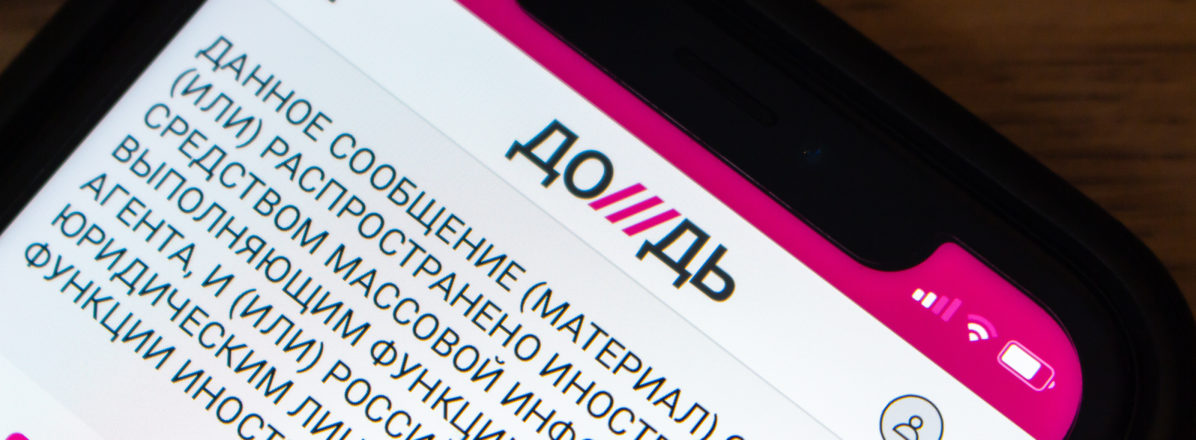

On Dec. 1, Aleksey Korostelyov, the host of Russian opposition TV channel Dozhd (TV Rain) broadcasting from the Latvian capital Riga invited his viewers to share testimonies about Russia’s mobilization process and problems in the Russian army. At the same time he expressed hope that “we also helped many military personnel, namely by assisting with equipment and bare necessities on the front line.”

The idea that an opposition journalist might be hoping to assist Russian soldiers provoked immediate outrage in Latvia, Ukraine and beyond. On Dec. 2, Dozhd issued an apology, insisting that the channel has never provided any assistance to the Russian military and fired Korostelyov. In a Facebook post, the journalist himself noted: “It is always humiliating to justify oneself, but it is probably necessary to clarify.” He denied sending goods or money to the Russian army, but underscored that he does feel sorry for the mobilized soldiers “hungry and abandoned by everyone.”

On Dec. 6, the Latvian broadcasting regulator (Nacionālā elektronisko plašsaziņas līdzekļu padome, NEPLP) canceled Dozhd’s broadcasting license, pointing out that Dozhd has already been fined twice for infractions: first, for using a map that included Crimea in the territory of the Russian Federation and referring to the Russian Federation’s army as “our army,” and then failing to provide Latvian language voice-overs to their programs, as required by law.

This article will first discuss the deeper underlying problems that shape Dozhd’s relations with its host country’s society and then look at the most recent reactions to NEPLP’s decision.

Lingering imperialism in Russian opposition

The Dozhd affair sheds light on obstacles in Latvian (and Baltic) cooperation with the Russian opposition that exist despite the common desire to see the fall of President Vladimir Putin’s regime. It also reveals a certain confusion among Western observers about why Latvia might be unwilling to overcome these obstacles for the sake of this common goal.

The explanation to both questions is simple and complicated at the same time. Baltic governments are interested in undermining Putin. That is the reason why Dozhd and other Russian independent outlets such as Meduza, Novaya Gazeta Europe, and iStories are operating from Riga. At the same time, this support for the Russian opposition has its limits: When the strategies used to undermine Putin’s regime risk harming either Baltic countries or Ukraine, Baltic national interests and those of Ukraine obviously prevail. The scandal surrounding Korostelyov’s remarks is exactly such a case.

The debate about Korostelyov’s comment has often been reduced to the question of whether Dozhd actually had been providing material assistance to Russian conscripts. The TV channel has denied this rather unbelievable possibility. Yet, the meaning behind the words “I hope that we also helped many military personnel with equipment and bare necessities,” has never been explained either by the journalist himself or by his former employer.

The unlikely material support seems to be the straw man that hides two more important issues: the framing of Russian soldiers as victims and the desire to improve their situation. From this perspective the issue is not just a phrase pronounced by one journalist, but a much larger question of how Dozhd should conceptualize its relations with the Russian army. In an interview with The New York Times given after his dismissal from Dozhd, Korostelyov admitted understanding that “even moral support for Russian conscripts fighting an illegal war on occupied territory could indirectly contribute to Ukrainian deaths.” But he still insisted that he will “not assume a position that will turn me from a Russian journalist into a person who defends the interests of other people.”

These words highlight a problematic trend in parts of the Russian liberal opposition and media: Standing against Putin or even being against the war does not always mean supporting Ukraine. In other words, the Russian opposition is not free from Russian nationalism rooted in Russian imperial tradition.

Whether Korostelyov’s views represent the views of his colleagues at Dozhd is an open question. His dismissal seems to indicate that the TV channel as such might not share his attitude. At the same time Korostelyov’s sacking was not met with unanimous approval by the Dozhd team. Two of his colleagues resigned in protest and Dozhd’s owner, Natalya Sindeyeva, expressed both compassion for the Russian soldiers — which she called “our guys” — and, after the revocation of the license, regret over Korostelyov’s sacking. Meanwhile, while participating in a discussion on Latvian national television, the editor-in-chief of Dozhd, Tikhon Dzyadko, insisted that Sindeyeva had expressed her personal opinion and that he was not planning to re-hire the sacked journalist.

There may be several diverging opinions inside the Dozhd collective. Yet it is surprising that this essential question — what is the Russian army to Dozhd? — was not clearly defined before relocating to Latvia, as it has both legal and moral implications. It might be that it is easier to undermine Putin’s regime in Russia by appealing to the suffering of Russian soldiers rather than the suffering of Ukrainian civilians. Yet it is not a strategy suitable to be deployed from Riga, the capital of a country that feels endangered by the very same soldiers and one that has made supporting Ukraine its top priority.

Ten months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, nobody sees assisting the Russian opposition as a crucial task for the Baltic states. On the contrary, there is the growing feeling in these societies that any attempts to change Russia’s internal dynamic from the outside are futile and that their involvement in any Russian affairs should be limited to the minimum. By hosting Dozhd, the Latvian government undertook the risk of angering part of its electorate. Yet Dozhd likely never realized this because, as noted in the columns of iStories — another exiled Russian news outlet located in Latvia — Dozhd never paid attention to the local dynamics of its host country. This was a fundamental mistake. There is a long and unpleasant history of newcomers from the Soviet imperial center settling in Riga without bothering to become interested in local societies — most Latvians have no patience with behaviors that repeat these patterns.

The Korostelyov affair erupted after Dozhd had already been fined twice: for showing a map in which Crimea was displayed as part of Russia and calling the Russian army “our army,” and for failing to provide Latvian-language voice-overs for its programs. The TV channel explained that the use of the misleading map was a technical mistake. The use of similar maps was the main reason why Dozhd was banned from Ukraine in 2017.

However, Dozhd stood by its decision to call the Russian army “our army,” despite the fine. After Dozhd’s license was revoked, anchor Ekaterina Kotrikadze argued that this wording was used to talk about crimes committed by the Russian army and implied that using other phrasing would have been a dishonest rejection of responsibility. “We are not going to pretend we have come from the moon,” she pointed out. This however is not correct. Dozhd anchors have used the wording to talk about the deterioration of Russian armed forces that led to the need for mobilization, as well as to frame Russian soldiers and Ukrainians as being victims of the same war. Whether this type of wording helps Dozhd in their efforts to undermine Putin is debatable, but from the Latvian perspective, it is obvious that it creates a sense of proximity and sameness between Dozhd audiences in both Russia and Latvia and the Russian army. This, of course, is not a sentiment that Latvian authorities are willing to foster. If Dozhd had paid attention to the mood of their host society, they would also have noticed how counterproductive for their own interests it was to claim a connection with the Russian army that is perceived as an existential threat by the majority of Latvians.

While Kotrikadze claimed that despite being relocated to Riga, Dozhd is still a “Russian channel,” legally it has become a Latvian channel. Dozhd’s disregard for this rather important “detail” has given rise to their third problem. All Latvian TV channels are required by law to provide a Latvian language voice-over option for all their programs. While this might be bothersome and expensive in the eyes of a news channel that mainly targets ethnic Russian audiences, it is the national law. Dozhd failed to obey this regulation and when fined for it, went to court to challenge the requirement. A basic knowledge of Latvian history and current politics would have helped Dozhd realize that even if the court ruled in their favor, no money saved from omitting the voice-over would be worth the damage this move did to their image. Latvian language is key to the Latvian national identity and a visceral issue for a society that is still marked by the traumatic experience of the Soviet-era nationality policies.

The impression that many Russian liberals are operating under an imperialist mindset was reinforced by some of those who came to Dozhd’s defense. For example, Vladimir Milov, an advisor to opposition leader Alexey Navalny, ridiculed Latvia’s position as shallow bickering about unimportant issues, and expressed hope that “older comrades” will explain to the Latvian government how it should act. This and other displays of post-colonial contempt toward Latvia obviously do not resonate well with Latvian society. As pointed out by Kirill Martynov, editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta Europe, also based in Riga: “The authors who think that they are supporting Dozhd with insults against Latvia are mistaken. With such friends, there will be nothing left of [Dozhd’s] reputation.”

Threatening national security?

Despite a general resentment toward Dozhd and their defenders, NEPLP’s decision to remove their broadcasting license was not unanimously celebrated in Latvia. Those supporting the decision interpreted the TV channel’s actions and ambiguities in the worst possible light. Those claiming that a fine would have been a more appropriate reaction gave Dozhd the benefit of doubt and argued that the TV channel had earned one last chance by promptly dismissing Korostelyov.

The Latvian Journalist Union stated that NEPLP’s decision was disproportionate, insisting that while Dozhd had committed grave mistakes, it should not be “pushed back to the Russian world, such as defined by the Kremlin.” Meanwhile, the chair of Ukrainian Congress of Latvia, as well as a number of activists, expressed strong support for NEPLP’s decision, accused Dozhd of serving Kremlin’s interests and criticized Latvian journalist for supporting their Russian colleagues.

While many saw the NEPLP’s decision as beneficial to Latvia and Ukraine, Jānis Sārts, director of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence based in Riga, tweeted that the number one beneficiary from the Dozhd affair was the Kremlin. Without further explaining his position, Sārts hinted at a successful Russian reflective control operation being conducted in Latvia, probably implying that Russia has managed to impact the assumptions upon which the Latvian decision has been made.

This particular point of why and how Dozhd actions were assessed and evaluated as threats to national security became an important question in Latvian internal debates.

Initially, it seemed that NEPLP’s decision had been first and foremost rooted in an undisclosed letter from the State Security Service (Valsts drošības dienests, VDD), the Latvian counterintelligence and internal security agency. However, on Dec. 7 during a talk show on national television, Director of NEPLP Ivars Āboliņš explained that the letter had been only “a small piece of the puzzle” and that even without the letter, Dozhd’s license would have been revoked. The VDD has recommended declaring Korostelyov (who resides in Georgia) persona non grata in Latvia and has warned editor-in-chief Dzyadko that providing financial or material support for the Russian army would be a criminal offense, but has not taken any action against the channel as such. Their statement appears to indicate that VDD has labeled Korostelyov’s words but not Dozhd’s overall activity “as contrary to the security interests of Latvia.”

Thus, it seems that NEPLP’s ruling was, after all, based on already publicly available information and NEPLP’s own judgment of the gravity of Dozhd’s actions. While every fine that Dozhd had received was well deserved, the national security threat label seems to be exaggerated. NEPLP’s arguments that the lack of Latvian language voice-overs was a threat to national security or that the use of “our army” might have led viewers to believe Dozhd was referring to Latvian armed forces do not seem to be convincing. The question about the third violation is debatable: Korostelyov’s message as aired on Dec. 1 is indeed contrary to Latvia’s security interests. Yet, Dozhd fired him immediately and once again reaffirmed their view that Russia’s war against Ukraine “was criminal and despicable.” While legally NEPLP was within its rights to remove the license, it was also possible to limit punishment to a significant fine.

As noted by Executive Director of the Baltic Center for Media Excellence Gunta Sloga, it is also alarming that a media outlet in Latvia can be closed so rapidly. Furthermore, details about the closure were initially unclear. The explanation first shared by NEPLP head Āboliņš seemed to suggest that Dozhd had not been questioned regarding the Korostelyov affair because their representative arrived to a meeting without a translator, expecting other participants to speak Russian. However it later became clear that while such an incident had occurred in the past, NEPLP had not communicated with Dozhd after Dec. 1, when Korostelyov’s words were aired.

In this context, journalists from Latvian news portal TVNET questioned Āboliņš over his own past. In 2014, five years before becoming the director of NEPLP, Āboliņš had tweeted both praise for Putin’s Crimea annexation speech and denigrating comments about Ukraine. Āboliņš apologized for his past views claiming that they were based upon the information he possessed at the time. This, however, raises further questions regarding the sources of information he used in 2014, and the quality of his own media literacy skills at the time.

While Āboliņš’ past deeds do not make him automatically wrong in the Dozhd case, they do point to serious issues in Latvian internal politics: In 2020, Latvian public radio reported that Āboliņš had close ties with the right-wing party National Alliance, which at the time was attempting to gain influence over NEPLP. Whether the party and Latvian parliament in general have been aware of Āboliņš former views regarding Putin and Ukraine is an open question.

With a different board, NEPLP probably would have made a softer decision, fined Dozhd and given them one last chance. Dozhd, with more interest in their host society and a clear attitude towards the Russian army, would not have run into problems with Latvian authorities. It has taken two to tango — and there is a possibility that the tune for this dance was played from Moscow. At the same time, one also cannot overlook the imperial legacies that have shaped the clash: Those who have been marginalized and dominated by empires are often hypervigilant to all manifestations of imperial practices; meanwhile, those who come from imperial centers are often unwilling and unable to see imperialistic patterns in their own attitudes.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.