A nation must think before it acts.

Bottom Line

-

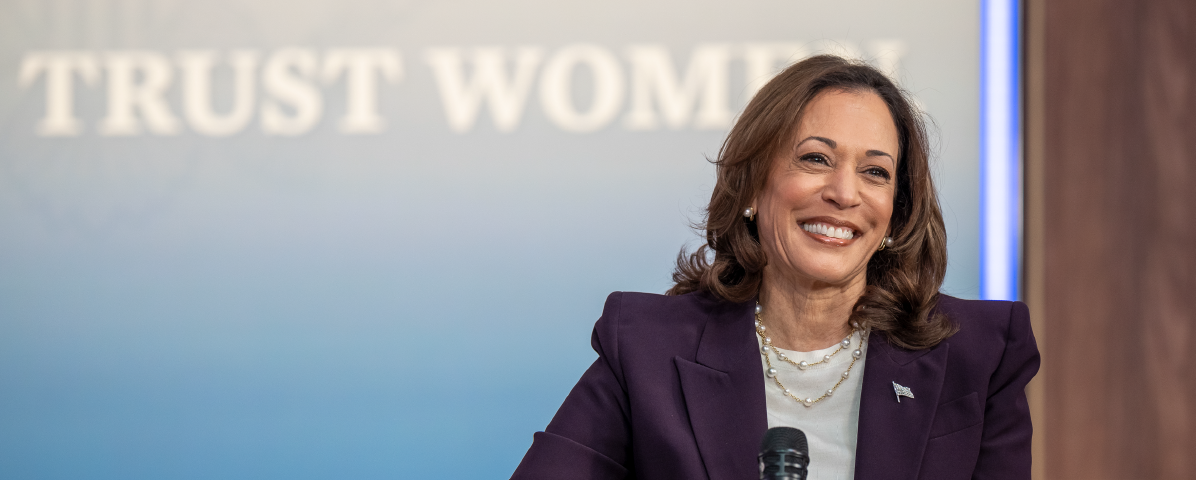

Commentators have searched for the “Harris doctrine,” or the essence of her foreign policy beliefs, as a guide to a potential Harris presidency

-

A presidential “doctrine” can refer to very different things—and some of these are predictable whereas others are not

-

International and domestic constraints are likely to channel a Harris presidency in a hawkish direction

In July, US President Joe Biden announced that he would not stand for a second term and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris as the Democratic candidate, triggering one of the great traditions of American politics: the search for a presidential doctrine, or the encapsulation of a leader’s foreign policy beliefs. A legion of journalists, scholars, and politicians began hunting for the “Harris doctrine” as a guide to what a Harris presidency might look like. Some said the Harris doctrine does not yet exist. Others claimed to have discerned the outlines of a clear agenda. For former president Donald Trump, the essence of the doctrine is weakness: “The Tyrants are laughing at her.” Meanwhile, commentators on the progressive left hope that a Harris presidency will mark a pivot away from American militarization and primacy and toward the pursuit of global justice.

One problem in identifying the Harris doctrine is that a presidential “doctrine” can refer to varying things: a presidential commandment, a leader’s inner compass, or their ultimate policy decisions. Each of these perspectives casts a different light on a potential Harris presidency. Taken together, they suggest that powerful foreign and domestic constraints are likely to guide a Harris presidency—to the surprise, relief, or disappointment of her critics—in a hawkish direction.

The Commandment

The first meaning of a presidential doctrine is the idea that an American president can make a single defining pronouncement, like etching a commandment into the tablet of US foreign policy. This can be a warning (thou shalt not) or an injunction (thou shalt), and it can be directed at foreign actors or fellow Americans. Curiously, presidents get to declare only one doctrine, so it is best not to play this card too early in an administration.

In 1823, President James Monroe issued the Monroe doctrine which instructed the European colonial powers to keep out of the Western hemisphere. Even though Monroe’s injunction was buried in a speech and the European powers largely ignored it at the time, over the decades it evolved into a fundamental principle of US foreign policy. A century later, in 1947, the Truman doctrine declared that the United States would aid countries threatened by communist subversion. In 2001, former president George W. Bush issued his own injunction: “Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

Will Harris declare a formal Harris doctrine? Of course, it is impossible to say. These commandments are highly unpredictable. Bush came to power in 2001 promising a “humble” foreign policy, but the 9/11 attacks triggered a dramatic and bellicose shift in his perspective. Harris might conceivably issue a doctrine to end American strategic ambiguity about Taiwan and announce that the United States will defend the island from Chinese attack. Or she could proclaim a doctrine about climate change, or human rights, or artificial intelligence. Voters will have to wait and see how Harris chooses to play this card. After all, if they knew the doctrine was coming, it would, in a sense, already exist.

The Inner Compass

The second meaning of a presidential doctrine is to capture the inner compass, or core foreign policy beliefs of a president. Here, a doctrine is about how a leader sees the world, guided by their personal experience, history, and memory—and how they stamp their perspective on statecraft. A doctrine implies individual agency and control and a president asserting their will over the environment.

The Obama doctrine centered on former president Barack Obama’s desire to avoid a repeat of the Iraq War. He saw Iraq as both a national debacle and a symptom of a wider and failed Washington playbook. Obama sought to dial down the militancy of Bush’s war on terror, responsibly withdraw from the Middle East, act with restraint, use limited force, and operate with allies. The 2011 US intervention in Libya was, in many ways, the opposite of the Iraq War. Washington fought as part of a broad multilateral coalition with limited US involvement. Ironically, the Libya intervention had the same outcome as Iraq, as Libya collapsed into civil war and feuding militias.

We can also understand the Trump doctrine in terms of Trump’s longstanding personal beliefs. For decades, Trump has held that allies and international institutions are taking America for a ride, and in 1987 he took out a full-page ad in the New York Times and other papers to rail against ungrateful US partners.

The Biden doctrine also captures the president’s decades-old proclivity for working with allies and partners, which he sees as a core element of American power.

Deciphering Harris’s foreign policy beliefs is far from straightforward. She is not a foreign affairs wonk with a clearly articulated diplomatic philosophy. Unlike Biden, she does not have decades of foreign policy experience and a body of major speeches and decisions. Her political career has focused more on domestic issues, especially before she became vice president. Harris did not think she would need a presidential doctrine any time soon. Until Biden’s debate with Trump in June, she was likely planning to complete another term as vice president.

And so, skeptics might wonder if Harris will simply default to Biden 2.0. Journalists often note that there is little space between the president and vice president. After all, she is already responsible for Biden’s policies, which represent the rough center of gravity in the Democratic Party. Some of her language on US competition with China as a struggle to win the 21st century is taken almost verbatim from Biden’s own speeches.

But Harris does have her own inner compass. Although she would enter office with less experience than Biden, she would have more experience than Bill Clinton, Bush, Obama, or Trump. She was a member of the Senate Intelligence and Homeland Security committees and traveled widely as a senator, including visits to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Israel. Of course, when Harris was vice president, Biden made the foreign policy decisions. But Harris was usually in the room and reportedly was deeply engaged in the process.

The idea that Harris was the immigration “czar” is a myth. However, she was tasked with a narrower mission focused on tackling the root causes of migration in Central America. In 2024, she helped to successfully ensure a democratic transition in Guatemala. Harris was involved in easing a squabble with France over the sale of US and British nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, which meant a proposed French sale of submarines was scrapped. Harris also met with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy numerous times.

If Harris has been widely engaged in foreign policy, what does she actually believe? Some on the left hope that she has underlying progressive sympathies. In 2020, as a senator, she declared: “I unequivocally agree with the goal of reducing the defense budget and redirecting funding to communities in need,” although she added, “it must be done strategically.” At times, Harris appears more sensitive than Biden to the concerns of the global South. As a senator, she backed a cut on arms sales to Saudi Arabia and wrote, “we need to end US support for the catastrophic Saudi-led war in Yemen, which has driven the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.” She voted to uphold the War Powers Resolution, which was vetoed by Trump, and curtail Trump’s power to wage war against Iran. She has been active in highlighting human rights abuses by China in Hong Kong and against the Uyghur population. Harris has described civilian casualties in Gaza as a “humanitarian catastrophe.” When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited Washington in July, Harris said, “We cannot allow ourselves to become numb to the suffering, and I will not be silent.”

But the differences between Harris and Biden over Israel should not be overstated. Harris routinely underscores Israel’s right to defend itself, opposes an arms embargo against Israel, and said the pro-Palestinian protesters who tried to shout her down would only help elect Trump to office.

And, in a wider perspective, Harris has a healthy respect for American power. “As commander-in-chief,” said Harris in her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, “I will ensure America has the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world.” If elected, Harris will be the first post-Iraq War president—in other words, the first president since Bill Clinton who was not, in some way, defined by the Iraq War and its lessons. Biden voted for war with Iraq, regretted it, and then became generally dovish after 2003. Obama’s doctrine was also defined by Iraq. Even Trump ran in 2016 against the Iraq War (despite having originally supported the campaign). By contrast, Harris, for better or worse, is “unburdened by what has been.”

She firmly denounced Russian aggression in Ukraine as “an attack on the lives and the freedom of the people of Ukraine,” as well as “an attack on global food security and energy supplies.” Harris may have a distinctive realistic streak. In private, she reportedly sees Biden’s characterization of global politics as a battle between democracy and autocracy as a simplification.

In sum, Harris is broadly aligned with Biden, but with some distinctive sympathies, and perhaps more importantly, some hard-edged tendencies.

Actions Speak Louder than Words

The third meaning of a presidential doctrine is the foreign policies that a president ends up pursuing—whether they are driven by the president’s personal beliefs or external constraints. In other words, a doctrine is the bumper sticker version of what a president actually does. This perspective recognizes that presidents rarely just stamp their will on foreign policy. “I claim not to have controlled events,” said Abraham Lincoln in 1864, “but confess plainly that events have controlled me.”

The Bush doctrine sought to transform global politics by using military force, unilaterally, if necessary, to combat terrorists and rogue states and spread democracy. But this doctrine did not emerge from Bush’s longstanding beliefs. Instead, after the 9/11 attacks, Bush bought into the hawkish and neoconservative agenda of his close advisors, as well as the broader public mood that demanded a militaristic response. If Al Gore had won the 2000 election, and if 9/11 had still happened, a hypothetical Gore doctrine might also have involved an expansive agenda to spread freedom and even the invasion of Iraq.

Similarly, we might understand the Obama doctrine—don’t do dumb stuff—as being less about the president’s unique personal reflections and more about a nation scarred by the Iraq experience and eager to turn the page on costly nation-building.

On foreign policy, Biden shifted from being a middle-of-the-road Democrat in the 1980s, to an interventionist hawk in the 1990s, to a relative dove after 2003. So which period represents the true Biden doctrine? The answer is all of them. Biden the hawk reflected the Clinton era of American primacy and humanitarian interventions. Biden the dove mirrored the dispiriting American experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What would Harris end up doing as president? Much like the idea of a doctrine as a commandment, it is hard to say. One prediction is that international and domestic pressures may mean that Harris becomes a foreign policy president and even exhibits a surprisingly hawkish posture.

First, the interlocking global crises in Ukraine, Gaza, Iran, Venezuela, and potentially Taiwan could dominate her attention. Although Americans are burned by the Iraq War experience and allergic to nation-building in the Middle East, the United States remains a hyper-interventionist power that rarely stays on the sidelines for long. For example, Russian President Vladimir Putin intends to deliver a strategic defeat to Ukraine—and by extension the United States—and Harris will be loath to see Ukraine lose on her watch, potentially ratcheting up US involvement.

Harris is almost certain to continue the frame of strategic competition with China and reinforce efforts to build a coalition of Western and East Asian states to balance Beijing, albeit while also looking for opportunities for Sino-US cooperation on issues like climate change.

In 2019, as senator, Harris criticized India’s decision to end the semi-autonomous status of Indian-administered Kashmir: “We have to remind the Kashmiris that they are not alone in the world.” But by 2023, when Harris was vice president and Washington saw India as a potential partner in the broader Sino-US competition, Harris praised Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi for his “role of leadership to help India emerge as a global power in the 21st century.”

Second, the Republicans are strongly favored to win the Senate in the November elections, and divided government in Washington D.C. may mean gridlock—stymying any ambitious Harris domestic agenda and further channeling the president’s energies toward foreign policy.

Third, a hawkish Harris presidency would align with a broader shift where Democrats have become more pro-military, and Republicans have become more skeptical of the military. For many on the left, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is part of a global fight for democracy, given Putin’s continued efforts to meddle in US elections. Trump’s sympathy for foreign autocrats and his attacks on US generals and the military as an institution have propelled many “never Trumpers” into the Democratic Party—like the veritable kettle of hawks, or 200-plus former staffers to Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney, who recently endorsed Harris for president. Harris certainly welcomes the chance to be seen as pro-military: “I will fulfill our sacred obligation to care for our troops and their families, and I will always honor and never disparage their service and their sacrifice.”

Fourth, her foreign policy team could reinforce an activist, and even muscular, policy. At first glance, Phil Gordon, who is Harris’s national security adviser and is tipped for a key role in a future Harris administration, seems like a dovish influence. His most recent book Losing the Long Game argued that American hubris and cultural ignorance spurred dangerous regime change operations in the Middle East. But Gordon is a pragmatic and centrist Democrat who believes the United States has significant interests in the Middle East, as well as a vital relationship with Europe, which could further encourage an activist policy. Harris has also promised to appoint a Republican to her Cabinet, and she may tap someone from across the aisle for a foreign policy position, just as Obama did when he kept Robert Gates on as secretary of defense.

Fourth, as a woman, Harris may face particular pressure to act tough in foreign policy and defy stereotypes of “weakness.” Researchers have found that female leaders tend to be more bellicose than male leaders—like Margaret Thatcher in the Falklands War—precisely because these “Iron Ladies” need to hammer home their national security credentials in a sexist world.

Harris the Hawk

In sum, the contours of the Harris doctrine depend on what we mean. It is impossible to say if she will issue a formal commandment—still less if other countries will follow her injunction. Her inner beliefs are murky but perceptible: She is a mainstream Biden Democrat with some distinctive attitudes. And what Harris would actually do as president is very much up for grabs, although powerful pressures may channel her administration in a hawkish direction. It is striking that Harris’s endorsements stretch across the political spectrum, from Bernie Sanders to Dick Cheney, the most iconic hawk of the post-Cold War era.

Harris may come to power with a domestic agenda and then end up focused on foreign policy. In 1944, former president Franklin Roosevelt decided to run for reelection, despite his doctor’s warnings that he might not finish a fourth term. FDR picked Harry Truman as his running mate, even though he barely knew him. Roosevelt died three months into his new term and Truman was suddenly thrust into the highest office. Despite a background as a Midwestern farmer and failed clothier, Truman became, to the surprise of many, a foreign policy president, and built the architecture of US national security in the emerging Cold War. The idea of taking over as president scared the hell out of him, he told his friends. But Truman had an underlying steel.

Harris was also thrust unexpectedly into a presidential race when Biden stumbled in the debate against Trump and then decided to bow out. And she has her own touch of steel, evident in a highly disciplined campaign that seeks to buttress her national security credentials. Harris’s inner compass and the prevailing winds may combine to produce a foreign policy presidency. For Harris, H is for Hawk.