A nation must think before it acts.

Bottom Line

-

The Czech Republic faces multiple security challenges as it prepares for parliamentary elections in October 2025.

-

Given the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and America’s putative disengagement from European security, Prague faces growing domestic debates on the way forward regarding continued support to Kyiv, increased defense spending, and the appropriate military equipment required for the country’s safety.

-

Czech President Pavel has assumed the lead position in defining the core security principles to which the nation must subscribe.

Czech President Petr Pavel, in a statement to the press on May 15, 2025, complimented the leaders of the country’s main political parties for their consensus on the core foundations of Prague’s current security posture. According to Pavel, “there is general agreement that at the present time Czech membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) provides the best guarantee of security and prosperity” for the Central European state.

While the general thrust of the president’s assertion may be true, the Czechs still face enormous security challenges in the coming months and years as a result of changing geopolitical realities in the region caused by the double whammy of the war in Ukraine and the return to power in Washington of an increasingly Euroskeptic administration. The leaders of the country’s disparate political parties may rhetorically express fidelity to the EU and NATO, but stark fissures in that perceived unity will almost certainly surface in the run-up to parliamentary elections scheduled for the beginning of October 2025.

In fact, ructions are already percolating across the political spectrum over the appropriate level of funding for the Czech Ministry of Defense, the relevant military kit suitable to support the armed forces’ mission, continued military and financial support to Kyiv, and balancing Prague’s EU and NATO commitments with its historic preference for security cooperation with Washington. How these issues play out will influence the upcoming elections and, in turn, be affected by the results of said polls.

The Historical Backstory: America the Beautiful

In a letter to the US President Woodrow Wilson in the waning months of World War I, Thomas G. Masaryk, the soon-to-be inaugural president of the modern Czechoslovak state, profusely thanked Wilson for America’s support of democratic principles and his championing of self-determination. Expressing the heartfelt appreciation of the Czechs, Masaryk wrote “Your name, Mr. President, as you have no doubt read, is openly cheered in the streets of Prague, our nation will forever be grateful to you and to the people of the United States. And we know how to be grateful.”

Although the Czechs’ feelings of affinity for America were overtly suppressed during the four decades of communist darkness that befell the country in the second half of the 20th century, the love affair reached new heights in the 1990s, in the immediate aftermath of the end of the Cold War. With a pro-western president, Vaclav Havel, ensconced in the Prague Castle (Hradčany) and a sympathetic Clinton administration, whose foreign policy toward Central Europe was driven primarily by Prague-born Madeleine Albright, the US-Czech relationship was the envy of Europe.

The importance of the renewed ties between Prague and Washington was highlighted in February 1990 when Havel, a mere two months after becoming Czechoslovak President, became the first post-communist leader from Central Europe to address a joint session of the US Congress. In the speech, the “philosopher king” presciently implored the body to strongly support Russia in its transition from dictatorship, stating, “I can only say that the sooner, the more quickly, and the more peacefully the Soviet Union begins to move along the road toward genuine political pluralism, respect for the rights of nations to their own integrity and to a working that is a market economy, the better it will be, not just for Czechs and Slovaks, but for the whole world.”

It is also worth noting that every US president from George H. W. Bush through Barack Obama visited Prague during their term in office. This executive-level attention to a modest-sized, relatively nonstrategic piece of real estate in Central Europe was not lost on the Czechs, who prioritized the country’s close ties to Washington over even their deepening bonds with their European partners.

This was particularly conspicuous in the security realm as the Czechoslovak military until 1992 and then the Czech Army, following the 1993 “velvet divorce” creating separate Czech and Slovak states, put boots on the ground in almost every US-led multilateral military engagement—Iraq (1991 and 2003), the Balkans (1990s), and Afghanistan (2000s)—since the fall of the Iron Curtain.

It is not surprising that Prague has looked to Washington for tangible, hard power support, as the past century has taught the Czechs bitter lessons about the reliability of their supposed European allies in times of need. The Munich conference in September of 1938 is remembered for the allies’ tragic appeasement of Adolph Hitler. For the Czechs, it represented the end of their post–World War I democratic and economic renaissance. At the end of World War II, in the spring of 1945, it was the US General George Patton and the Third Army that liberated western Bohemia from Nazi oppression.

Fast forward twenty-three years, and Europe stood idly by as Soviet (mostly Russian) troops stormed into Czechoslovakia in August of 1968 to crush the “socialism with a human face” movement, sentencing the country to another twenty years of economic and political stagnation. Consequently, over the past century, the Czechs have developed a hard-earned skepticism about well-meaning, but often hollow, promises of support from Western European capitals.

What to Do About Ukraine

Prague’s preference for the American security umbrella has been sorely tested, however, over the past decade. Starting in 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and launched a low-level conflict in Eastern Ukraine, serious splits in the Czech political arena have surfaced over the wisdom of pursuing an exclusively America-centric defense posture. Miloš Zeman, the Czech President from 2013 to 2023, throughout most of his time in office served, in fact, as an informal spokesman in Central Europe for Russian President Putin’s propaganda machine, often criticizing Washington in the process. It was only the Kremlin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine in late February of 2022 that convinced Zeman of his error in previously parroting the Russian narrative.

It is the Ukraine conflict and the West’s response that has become one of the Czech Republic’s main security challenges. Since the start of the war, the Czechs have been a model European state, providing significant military kit to Kyiv, highlighted by a Prague-led initiative to supply Ukraine with large-caliber ammunition, funded by partners from NATO allies. In 2024 alone, the program furnished Kyiv with 1.6 million rounds of ammunition, with one-third of the total being critical 155mm shells.

Equally important for Ukraine has been the Czech Republic’s humanitarian support to a wave of refugees fleeing the war-torn country. In the past three years, the Czech government has spent approximately 62.5 billion (USD 2.6 billion) Czech Crowns (CZK) on assistance to Ukrainian refugees. Furthermore, the government and the citizenry writ large have overwhelmingly welcomed the influx of displaced persons, effectively and promptly assimilating them into Czech society.

The combination of the return to power in Washington in January 2025 of a Ukraine-skeptic administration and the increasing uncertainties surrounding an equitable—from Ukraine’s standpoint—conclusion to the war have heightened the domestic political friction regarding Prague’s policy going forward. While President Pavel and the governing SPOLU (together) coalition remain staunchly pro-Kyiv, opposition parties, seemingly inspired by US President Trump, are openly questioning the government’s “as long as it takes” support for Ukraine.

The main centrist Czech opposition party, ANO (Czech: Akce nespokojených občanů: action of dissatisfied citizens), has called into question its support for the aforementioned provision of munitions to Kyiv. In early 2025, in an interview for the Czech weekly magazine Respekt, Karel Havlíček, ANO’s shadow prime minister, stated unequivocally that if the party returns to power, it would no longer participate in the ammunition initiative.

For its part, the right-wing SPD party (Czech: Svoboda a přímá demokracie: freedom and direct democracy) has consistently criticized the government’s pro-Ukraine policies. The party, in May 2025 projections released by the Median polling agency, is the third most popular after ANO and the ruling SPOLU coalition. Given the likelihood that both of these opposition parties will form the core of a new coalition government following the October ballot, significant policy adjustments regarding the Czech Republic’s stance toward Ukraine are almost a certainty.

How Much for Defense

The appropriate level of funding for the Czech Ministry of Defense is another policy debate that poses significant challenges for the current and future cabinets in Prague. While the Fiala government has gradually increased financial support to the country’s defense establishment, the Czechs only reached 2 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2024. Like for many of its NATO brethren, the Russian invasion of Ukraine proved to be the main incentive for Prague’s commitment to higher defense budgets, which was a paltry 1.4 percent of GDP in 2021.

The Czechs had precious little time to celebrate attaining the required 2 percent of GDP level as the funding goalposts quickly changed with Donald Trump’s return to the White House in January 2025. Suddenly, Prague and other vulnerable Central European NATO states were faced with demands from Washington and alliance headquarters in Brussels to redouble funding efforts to 3, 4, or even 5 percent of GDP. The new defense spending recommendations were accompanied by heightened concerns in the center of the continent that the United States under Trump 2.0 could disengage from Europe.

To the Czechs’ credit, Prime Minister Fiala and his coalition immediately refocused their efforts to increase funding in response to the new geopolitical realities facing NATO. In March 2025, the government reached an agreement to increase Czech defense spending in increments of .2 percent of GDP in each of the next five years, reaching a target of 3 percent of GDP by 2030. In justifying the new defense expenditure goals, Fiala stressed that “we are experiencing a change in the international order . . . there’s a war raging not far from us . . . and we must be capable of defending ourselves.”

While acknowledging the need for additional monies for defense in light of the reality of Russian revanchism, the main opposition party, ANO, has been vociferous in its criticism of the government’s monetary policy writ large and specifically the perceived lack of transparency by the Fiala regime in how the increased security funding will be spent. In a March 2025 letter to the prime minister, ANO leader Andrej Babiš lambasted the coalition’s “pointless and nontransparent squandering of taxpayer money to, on paper, raise defense spending.” The letter highlighted an ancillary aspect of the security dilemma facing the country: on what to spend the increased investment for defense?

How to Spend Those Funds

Although there is general agreement among the Czech political elite on the need to increase the country’s defense budget, serious arguments remain as to how best to invest those monies. At the heart of this debate is the current government’s decision to purchase at least 24 F-35A Lightning II multi-role fighter jets from the United States for a whopping 150 billion CZK (approximately $6.6 billion). The aircraft will replace the bulk of the Czechs’ current fighter inventory and, ostensibly, further integrate the country into NATO’s strategic defense plans.

Given that Czech defense expenditures for 2024 were 166.8 billion CZK (approximately $7.7 billion), the outlays for the American fighter represent an enormous investment. The cost, however, is not the only point of contention regarding the deal as critics have seized on the Trump administration’s presumptive wavering commitment to Europe’s defense to question the wisdom of the deal. In that vein, Robert Králíček, ANO’s expert on security questions, condemned the fighter deal in April 2025 for two reasons: sending Czech defense money abroad instead of supporting the country’s indigenous defense industry and tying the Czech Republic’s future well-being to a potentially unreliable country.

Even the centrist Czech weekly Respekt, rarely a friend of the opposition ANO movement, called into question the F-35 deal. In a late February 2025 editorial, journalist Marek Švehla excoriated the government plan plaintively pondering, “isn’t it now risky to buy fighter aircraft from a country that is in cahoots with Putin?”

Notwithstanding the growing disquiet in Prague regarding America’s reliability, legitimate questions remain about whether advanced fighter jets offer the best solution for the country’s future security requirements. Based on Ukraine’s struggles to repel continuous waves of Russian airborne attacks, improved capacity in Czech air defense systems, rather than the latest tanks or all-weather fighters, likely represent a more appropriate use of expanded budgets. This issue will undoubtedly persist through the upcoming early October 2025 general elections.

President Pavel Pushes a Security Bottom Line

It is against this backdrop of cascading security challenges that President Pavel has exerted extensive pressure to facilitate general agreement across the Czech political spectrum on the core foundations of the country’s defense posture. The Czech head of state, who previously served as the chief of the general staff of the Czech Armed Forces and as chair of the NATO Military Committee, is a key figure in the current security debates within the country’s political domain. Critical to the president’s arguments have been the country’s memberships in both NATO and the EU as nonnegotiable guarantees of Czech security. Pavel’s efforts in this regard have included meetings with the leaders of the current parties in parliament, statements in remembrance of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, discussions with visiting foreign dignitaries, and participation in security-related events.

In this view, the Czech leader has been at the forefront of finding common ground among disparate political parties regarding the key foundations of the country’s defense posture. In mid-May 2025, Pavel called the leaders of each party represented in the current parliament for individual talks at Hradčany on the issue. The president took heart from the results of the meetings where, according to Pavel, even the far-right SPD did not question the country’s NATO and EU membership. Furthermore, all of the party leaders concurred with the need to increase defense spending, although with divergent views on how to invest those funds.

In addition, the Czech head of state has used appearances at international forums to convey his narrative of the Czechs’ responsibility, along with the rest of NATO, to take more responsibility for their own defense. Opening the 2025 Globsec conference in Prague on June 12, 2025, Pavel remarked that “we need to ensure that we’ll be capable of defending our interests, if necessary, without active American support.” He struck a similar theme four months prior at the Munich Security Conference when, during a panel discussion with other European leaders, Pavel opined that Europe “is at a turning point. Europe can show that it is ready to take responsibility” for its own defense.

President Pavel, since the beginning of 2025, has also made consistent statements to inculcate in the Czech citizenry the core precepts of Czech defense policy. Bearing in mind that stark divisions of opinion on these issues across Czech society mirror those expressed by the country’s politicians, the former general’s appeals to unity face an uphill battle. Nevertheless, in a wide-ranging interview with Czech Television (ČT24) on his two-year anniversary of assuming the presidency, Pavel called for all of Czech society to participate in the country’s security. “We all must feel a need to defend ourselves and that each of us is responsible for contributing to that security.”

A Critical Choice for Czech Voters

With the election campaign heating up ahead of the early October 2025 parliamentary polls, salient doubts remain whether the Czech public will consider Pavel’s injunctions when casting their ballots. While opposition leaders from the ANO movement have been generally supportive of the president’s more forceful prescriptions for Czech security requirements, weighty questions remain about their fealty to increased defense spending and NATO support for Ukraine.

The likelihood of an ANO-led coalition government returning to power in the fall persists as early May 2025 polling by the Kantar agency for Czech Television revealed that ANO led with 35 percent backing ahead of 19.5 percent for SPOLU. In a potentially more concerning survey from the Czech Institute for Empirical Research, 54 percent of Czechs surveyed believe that the current SPOLU coalition government will manipulate the elections in order to maintain power. This level of mistrust in the ruling parties bodes ill for their chances this October, with ANO, SPD, and other more extreme fringe parties the likely beneficiaries.

Whatever the outcome of the October plebiscite, the victorious coalition government will inherit multiple security dilemmas, the solutions to which will undoubtedly define the Czech Republic’s defense posture for years to come.

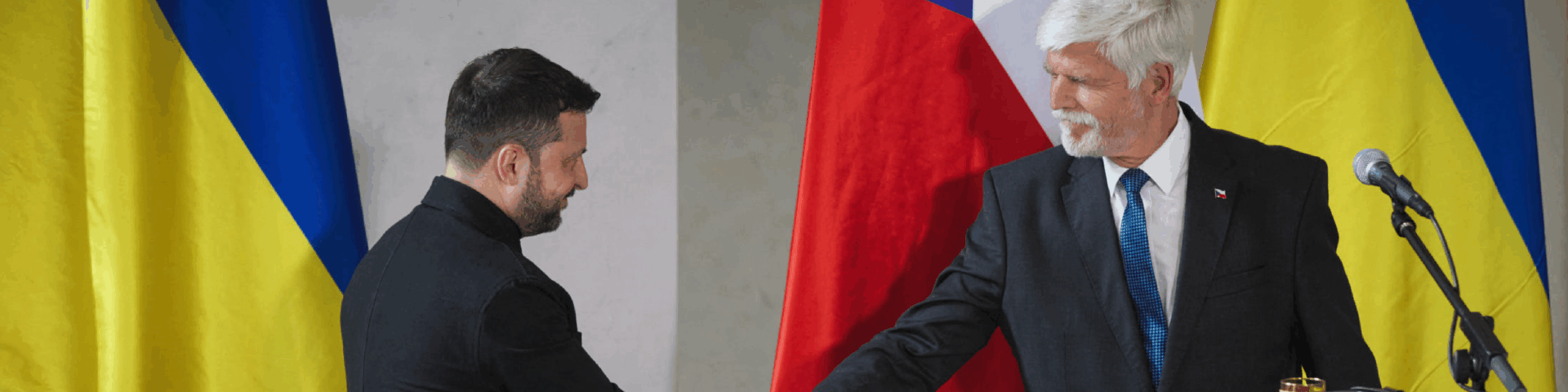

Image Credit: Czech President Petr Pavel and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky during the official visit of Volodymyr Zelensky and his wife Olena Zelenska to Prague, May 4, 2025. (President of Ukraine via ABACAPRESS.COM)