A nation must think before it acts.

When Beijing dispatched a relatively unknown rear admiral from its National Defense University to the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue, bypassing its own defense minister and forfeiting its plenary address, it did more than snub Asia’s premier security forum. It signaled a regime shifting from dialogue to confrontation. China has traditionally used the Singapore gathering to engage regional counterparts and frame its strategic intentions. By refusing the platform at a moment of rising tensions, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) revealed its preference for manufacturing crisis rather than managing competition.

This posture reflects more than diplomatic pique. It is the manifestation of what can be called strategic compression,[1] a condition in which a state’s decision space narrows even as the timeline for action accelerates. For China, compression arises from converging demographic decline, economic stagnation, and political rigidity. These forces produce a closing window in which Beijing perceives a diminishing opportunity to achieve its central project: the “national rejuvenation” with the main marker of absorbing Taiwan.

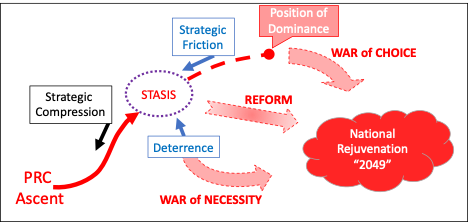

Washington must recognize both the danger and the opportunity this moment presents. The danger is that compression can drive Beijing toward reckless escalation, gambling that crisis or even conflict will preserve regime legitimacy. The opportunity is that deterrence, strategic friction, and off-ramp architecture can be leveraged to hold China in stasis, denying both a war of choice and a war of necessity.

Figure: “The Ascent”: Strategic Compression, Strategic Friction, and Deterrence Resulting in Stasis

Strategic Compression: A Closing Window

Compression is the pressure Beijing places upon itself; friction is the pressure others apply upon Beijing. Strategic compression is best understood as the simultaneous narrowing of options and acceleration of timelines that confront states when long-term ambitions collide with structural constraints. The concept is related to the classic “windows of vulnerability” debate in strategic studies. Lebow argued that leaders exploit perceived openings when adversaries are temporarily weak. Later scholars extended the idea: Doeser and Eidenfalk posited that foreign policy change often requires leaders to perceive a fleeting “window of opportunity” as both real and urgent. More recently, Hal Brands has tied these windows directly to great-power competition, warning that compressed states may lunge an advantage before their window of opportunity closes.

China today is a textbook case. Its demographic collapse (fertility below 1.1, shrinking labor force, and surging pension obligations) erodes both economic and military potential. Its economic stagnation (youth unemployment above 20 percent, debt-to–gross domestic product (GDP) ratios beyond 270 percent, and growth rates far lower than official statistics claim) undermines the CCP’s claim to technocratic competence. And its political rigidity (Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power, purges of technocrats, and reliance on loyalty over capability) reduces the very adaptability compression demands.

Compression is both structural and perceptual, but the latter is the primary force. Leaders act not on perfect information but on how they read the trajectory of time. In Beijing, the perception is that delay is fatal: the path to “rejuvenation” risks being blocked by demographics, debt, and dissent. The 2025 white paper, China’s National Security in the New Era, makes this explicit by subordinating economic growth to security priorities and framing Taiwan’s annexation as essential to CCP survival.

Strategic compression thus creates a dilemma. Beijing can attempt reform, a path of delay, though uncertain and historically resisted. Or it can gamble that crisis, even conflict, offers the only way to break through the narrowing window. In either case, time itself has become China’s adversary.

CCP Attributes Under Compression

Demographic and Economic Decline

The CCP’s legitimacy has long rested on two pillars: rising prosperity and national rejuvenation. Both are faltering. China’s demographic decline is accelerating faster than even pessimistic forecasts predicted. Fertility rates have fallen below 1.1, population peaked in 2022, and the working-age cohort is shrinking by millions annually. The consequences ripple across the system: labor shortages, surging pension obligations, and a contracting pool for military recruitment.

Economic performance tells a similar story. While official figures continue to advertise ~5 percent GDP growth, independent estimates suggest real growth is half that. Youth unemployment (officially “suspended” from publication in 2023 after surpassing 20 percent) reflects a generation losing faith in the promise of upward mobility. Debt-to-GDP ratios above 180 percent, and likely closer to 300 percent by some estimates, reveal an economy built on fictitious capital and financial engineering. Foreign investment, once the backbone of China’s integration into global markets, has collapsed. These are not cyclical dips but structural stall points of a peaking great power.

Narrative Control and Crisis Politics

Authoritarian systems compensate for stagnation with propaganda. Xi Jinping has tightened control over media, education, and party messaging to frame China as besieged by hostile forces determined to block its rightful rise. The 2025 National Security White Paper codifies this framing, subordinating economic goals to regime security and elevating Taiwan’s annexation as a matter of existential survival.

This narrative thrives in crisis conditions. The CCP has demonstrated repeatedly that crises, whether real or manufactured, strengthen its grip. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Beijing justified draconian controls as national defense of health. Maritime coercion against the Philippines or Taiwan is framed as a reactive defense against foreign encroachment. Even violent repression, from Tiananmen Square in 1989 to Hong Kong in 2019, was justified as necessary to preserve the party’s survival. The lesson Xi has drawn is that crisis validates the party; war, by contrast, carries existential risks that could expose regime fragility.

Gambling for Resurrection

Yet compression creates pressure for escalation. Downs and Rocke describe this dynamic as “gambling for resurrection”: when embattled leaders, facing declining legitimacy or looming failure, take high-risk actions because the downside is already existential. Xi’s tightening personalist system makes this risk acute. At seventy-one, his own legacy timeline intersects with China’s demographic and economic timelines. Having purged rivals and eliminated dissent, he has no safety valves left.

This is why strategic compression is so dangerous. For a regime that thrives in crisis but not in war, the narrowing window may incentivize exactly the kind of reckless gamble that could prove catastrophic: a rapid strike against Taiwan before optimal readiness, or a manufactured external confrontation to rally internal legitimacy. These would not be rational wars of choice but desperate wars of necessity, undertaken not because success is assured, but because delay appears fatal.

China’s Strategic Position Summarized

The CCP today faces a paradox. It possesses the world’s largest navy, expanding nuclear forces, and formidable coercive tools in the gray zone. Yet its foundations, population, economy, and governance are eroding. This creates a system both powerful and brittle: strong enough to coerce neighbors, weak enough to fear internal unraveling. In such a system, strategic compression does not just narrow options; it warps incentives. It encourages Beijing to equate inaction with defeat and to view the crisis not as a danger to avoid but as a tool to embrace.

US Responses to Strategic Compression

Strategic compression places Beijing at a dangerous crossroads, but it also creates space for Washington to shape outcomes. By applying complementary lines of effort (deterrence, strategic friction, and off-ramp architecture), the United States and its allies can deny both a war of necessity and a war of choice, holding China in stasis until its internal contradictions resolve themselves.

Entrapment in a limited war may look tempting, but it runs counter to the logic of compression: Beijing thrives in crisis, not in sustained conflict. A limited clash risks providing the CCP the very external confrontation it seeks to rally domestic legitimacy, tighten control, and divert attention from internal fragilities. By contrast, enforced stasis denies both the war of necessity and the war of choice, leaving China suspended between ambition and decline. The United States gains most not by provoking conflict, but by letting compression do its work; time erodes Beijing’s foundations far more reliably than a limited war that could backfire into wider escalation or regime consolidation.

1. Deter the War of Necessity

The most immediate risk is that Beijing, fearing the window closing entirely, chooses to act before it is ready. This “war of necessity” would prioritize timing over preparation: a rapid strike on Taiwan or coercive escalation elsewhere designed to achieve fait accompli before US intervention.

To prevent this, deterrence must make such action prohibitively costly and uncertain of success. Forward-deployed US and allied forces across the first island chain should demonstrate visible readiness and credibility. Multilateral exercises with Japan, the Philippines, and Australia should underscore that any aggression will trigger collective resistance. Revealing previously unacknowledged capabilities (hypersonic weapons, extended-range strike systems, or integrated special operations force–space-cyber concepts) can inject uncertainty into People’s Liberation Army (PLA) planning.

Deterrence must also extend beyond the military. The precedent of SWIFT sanctions against Russia illustrates the power of coordinated economic punishment. A credible plan to cut China off from Western capital, food, or energy markets in the event of aggression would force Xi to weigh not just battlefield risks but the collapse of the regime’s domestic legitimacy. The goal is not to guarantee that the PLA cannot fight, but to ensure Xi believes he cannot win.

2. Strategic Friction Against the War of Choice

The second risk is a “war of choice,” Beijing’s preferred scenario, delaying conflict until it achieves optimal military readiness. Here, the United States seeks to deny the People’s Republic of China (PRC) the ability to offset or outrun the headwinds of its own compression.

This is the logic of strategic friction: imposing cumulative resistance that slows Chinese advancement without direct confrontation. Heath et al. and Mazaar et al. both discuss strategic friction, even so far as citing senior PRC officials describing their current state as such. Blocking acquisitions of semiconductor assets through Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States reviews, restricting technology transfer in artificial intelligence and quantum computing, and enforcing intellectual property protections complicate the PLA’s modernization path. Securing supply chains for rare earths, lithium, and other critical minerals prevents Beijing from leveraging global chokepoints for both military and economic coercion.

Strategic friction is effective precisely because it exploits Beijing’s compression: every delay magnifies the gap between ambition and capability. By raising costs, slowing progress, and diverting resources, friction ensures that China cannot achieve the conditions necessary for a successful war of choice before its demographic and economic decline forecloses the option.

3. Off-ramp Architecture: Illuminate Malign Activity and Accommodate Narrative Off-ramps

The third line of effort must address the CCP’s most resilient weapon: its narrative. Beijing thrives by framing the crisis as a defensive necessity. The 2025 White Paper casts Taiwan’s annexation not as an ambition but as a requirement for survival. State media and PLA messaging increasingly emphasize “inevitable conflict,” conditioning both domestic and international audiences to view confrontation as forced upon China.

Washington and its partners must illuminate malign activity. Rapid dissemination of PRC coercive actions, ranging from unsafe intercepts to maritime ramming, must provide undeniable evidence of Beijing as aggressor. Public diplomacy should contrast China’s rhetoric of defense with its record of expansion, elite capture, and debt-trap diplomacy. Indo-Pacific partners can be empowered through digital literacy campaigns and intelligence sharing to resist Chinese disinformation and build societal resilience.

Yet illumination alone is insufficient. Deterrence that only corners Xi risks triggering “gambling for resurrection” behavior. Washington must also shape an off-ramp narrative—a path that allows Beijing to de-escalate without humiliation. Sun Tzu warns the strategist to never place their enemy on death ground. Friction and deterrence must be accompanied with a release valve to deal with the frustrated energy. This could emphasize mutual restraint, regional arms control dialogues, or a face-saving role in global initiatives (climate, disaster response, infrastructure) that sustain legitimacy without confrontation.

By pairing firmness with off-ramps, the United States reduces the incentive for desperation gambles while strengthening the legitimacy of international norms. The narrative battle is thus about not only illuminating Beijing’s malign activity but also offering a win-win alternative that preserves peace without rewarding coercion.

Conclusion: The Moment of Maximum Danger

China’s 2025 National Security White Paper reveals insecurity, not confidence. By framing Taiwan’s annexation as essential to survival, the CCP is no longer managing competition but constructing a narrative of inevitability. This is how wars of necessity are manufactured out of wars of choice: by convincing leaders and citizens alike that crisis is not optional, but existential.

Strategic compression has brought Beijing to the edge of this dilemma. Demographic decline, economic stagnation, and political rigidity have narrowed its decision space while accelerating its timelines. Left unchecked, these pressures incentivize reckless gambles: a desperate strike before readiness, or a manufactured confrontation to consolidate legitimacy. Downs and Rocke’s “gambling for resurrection” dynamic captures this perfectly: when leaders believe time is running out, even high-risk conflict can appear preferable to decline.

Yet this moment of maximum danger is also the greatest opportunity for the United States and its allies. By combining deterrence, strategic friction, and off-ramp architecture, Washington can turn compression into the CCP’s constraint rather than its catalyst.

- Deterrence ensures that a war of necessity, acting now before readiness, is seen as prohibitively costly.

- Strategic friction denies Beijing the purchase to overcome the headwinds of its own compression.

- Off-ramp architecture efforts illuminate malign activity, counter Beijing’s siege worldview, and, crucially, shape off-ramps that prevent Xi from perceiving desperation as his only choice.

In the physics of compression, movement itself becomes the danger. Strategic friction must keep the CCP floating; denied the purchase to hurl itself through the closing window, yet held aloft from collapse. Perhaps this enforced stasis can prevent catastrophe.

Americans like decisive and extreme conclusions, but this will not fit for long-term rivalry. Although stasis is not victory, it is the necessary condition not only to prevent war, but also to thoughtfully check the regional instigator. With the order intact, America can resume its focus on economic interests.

[1] The notion of strategic compression draws from work on windows of opportunity and vulnerability (Richard N. Lebow, Between Peace and War: The Nature of International Crisis, Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence, Richard Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics), and more recent “peak power” arguments (Michael Beckley, Unrivaled: Why America Will Remain the World’s Sole Superpower, Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China]), as well as the concept of “gambling for resurrection” (George W. Downs and David M. Rocke, Optimal Imperfection: Domestic Uncertainty and Institutions in International Relations, all of which highlight how narrowing options and accelerated timelines can push states toward risk-acceptant behavior.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official policy or position of the US Department of Defense, the US Army, or the US government.

Image: Adobe Stock