A nation must think before it acts.

Introduction

Water-related conflict is among the key concerns for a future marked by rising incidences of droughts, increasing water scarcity, and growing demands. The main aquatic project that has shaped contemporary diplomatic relations in the Nile Basin is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Being the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa, with a maximal power production capacity of 5150 MW, it is capable of generating electricity for millions of Ethiopians and people in neighboring countries. Its construction started in 2011, and the final filling of its water reservoir was completed on Sept. 5, 2024. On March 20, 2025, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali reported that six out of 13 turbines were already operational, and announced the completion of the GERD project on July 3. The inauguration took place on Sept. 9 and was attended by several regional leaders, among them Kenya’s President William Ruto and Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud.

Since the first announcement of its construction, the GERD has sparked outrage in Egypt, historically the largest consumer of the Nile waters. According to Egypt, Ethiopia’s aquatic policies are threatening the survival of the Egyptian state by unilaterally taking control of the primary source of the Nile water, namely the Blue Nile. Letters to the UN Security Council have been exchanged, with Egypt repeatedly accusing Ethiopia of violating international law by continuing to fill the GERD basin without the approval of the downstream riparian countries. Ethiopia, in turn, argues that Egypt persists in undermining negotiations and points to its repeated threats of violence, while simultaneously stressing how the GERD can provide a mutual benefit. One of these additional benefits, Ethiopia argues, is that the GERD will be instrumental in avoiding future Nile floods throughout extremely wet years, which regularly threaten Khartoum, the capital of Sudan.

This article assesses the risk of escalation of the GERD conflict by analyzing different scenarios and drawing on factors that involve diplomatic posture, climate, and national water needs. Although Sudan is geographically located between the two countries, the central focus is on Egypt and Ethiopia due to their central roles in the dispute and Sudan’s limited influence in the region. The main finding is that, under the current GERD operational framework, Ethiopia would only be able to seriously harm Egypt’s access to water after a prolonged drought and if it simultaneously exhibits a hostile posture towards Egypt. Other factors, like increasing water demands from population growth, may also heighten tensions, even if unrelated to the GERD’s operation. Cooperative water management and advanced drought planning are therefore key in alleviating Egyptian concerns and in establishing a viable future for all three riparian countries.

The History of the Nile

The Nile is the most important river in Africa and has enabled civilizations to prosper for thousands of years. It is formed by the confluence of the White and Blue Niles, originating respectively in Lake Victoria in Uganda and Lake Tana in Ethiopia. During the summer monsoon, rainfall over Ethiopia feeds Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile, which accounts for about 85 percent of the Nile’s flow at that time and roughly 59 percent over the course of a year. The Blue and White Nile Rivers converge at Khartoum in Sudan, where they become the Nile proper. The Nile provides about 97 percent of Egypt’s water needs, and its basin has long been one of the most densely populated regions on earth. At present, more than 104 million people live in the Nile Valley and Nile Delta, only about 3–4 percent of Egypt’s land surface, in an area comparable in size to Catalonia or the Netherlands. Threats to the Nile have therefore always been seen as an existential risk to Egypt.

The first international law regarding the river was the 1929 Nile Water Agreement, a bilateral arrangement between Egypt and the United Kingdom, the former colonial administration, granting Egypt complete ownership of the Nile and veto power over upstream countries’ future decisions. In return, the United Kingdom would continue oversight over the Suez Canal, which they required to maintain the fastest shipping route to India. UN Treaty 6519 of 1959 granted Egypt 66 percent and Sudan 22 percent of the Nile’s flow, with the rest accounting for losses such as evaporation. Ethiopia, not having been a British colony, was left out of both agreements. The dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the ownership and use of the Nile has been going on since then, and the peaceful resolution of their disagreements has been the norm up until now, despite recurring bellicose rhetoric. Since the rule of Muhammad Ali in the first half of the 19th century, Egypt had been the main regional power and, therefore, de facto able to exert its rights. Due to climate change and growing populations in all riparian states, however, water scarcity has increasingly become a problem, leading to friction. When Ethiopia’s former leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, first proposed the building of hydroelectric dams in 1978, Egypt’s then-president Anwar Sadat considered it a red line: “We are not going to wait to die of thirst in Egypt. We’ll go to Ethiopia and die there.” This statement was in line with Article 44 of the Egyptian constitution, which stipulates the protection and maximization of the Nile’s use. No dam was built back then, but relations between the two countries slowly started to change. Since 2004, Ethiopia’s GDP has been growing approximately 10 percent per year, and it was even the world’s fastest-growing economy between 2013 and 2018. Along with changing power dynamics came the confidence to overtly reevaluate former treaties. Ethiopia asserted that it would not have to adhere to what were seen as “colonial” treaties, calling Egypt’s claim to the Nile “the most absurd thing you ever heard” and arguing for the right to use its resources as it saw fit.

When the 2011 Arab Spring saw Egypt’s president Hosni Mubarak deposed, Ethiopia took advantage of the situation and started construction of the GERD. Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam would more than double the country’s energy production by delivering over 5 GW/year. Ending energy poverty was urgent in Ethiopia, where, as late as January 2024, nearly 60 percent of the population (over 100 million people) still had no electricity. Without the help of foreign aid or investors, the dam was completely funded by Ethiopians through donations and special bonds. As such, the GERD became a national symbol, unifying over 80 different ethnic groups, and people became personally invested in the project. Yielding to Egyptian pressure would risk major financial loss, hinder Ethiopia’s development, and threaten national unity in an already politically unstable country.

Figure 1: Flow of the Nile and the GERD. (Source: National Geographic)

To operate the dam, its reservoir had to be filled to maintain a steady flow through the turbines. Despite Egypt’s and Sudan’s concerns, short-term from filling the reservoir and long-term over Ethiopia controlling the Blue Nile flow, no treaty on water management was ever signed. Furthermore, Egypt repeatedly stressed its concerns about the dam’s safety, the lack of oversight by international experts, and what its finalization would mean for the energy production of its own hydroelectric dam, namely the Aswan High Dam (AHD). Most importantly, Ethiopia declined to commit to specified volumes of future water flows to Sudan and Egypt, instead insisting on non-binding mechanisms to resolve disputes. Addis Ababa, in turn, emphasized the mutual benefits of the dam: generating power for export purposes and preventing seasonal flooding of the Blue Nile. These arguments did not reassure the downstream countries. With a population that has more than doubled within the last 30 years, around 20 percent of the total labor force working in agriculture, and unemployment rates that occasionally approach those of the period just before the 2011 revolution, the lack of certainty regarding the Nile is a continuous thorn in Cairo’s eye.

There are, thus, two sides to the Nile dispute. Egypt, the historical master of the river, regards the GERD as an existential threat to its water supplies, while Ethiopia regards it as necessary for its progress. The question remains, though, whether these differences are irreconcilable.

The Present Situation

Construction of the dam was finished in 2020, and the first filling of its reservoir occurred in the same year. During the filling phase, some became optimistic because it did not lead to a decline in downstream reservoir water. Egypt’s greatest fear had not materialized, while the most significant hurdle had been overcome. However, such optimism had been partially confounded by excessive rainfall in Egypt during the filling of the GERD´s reservoir, a rare occurrence at the right moment. The unseasonable wet weather made Egypt less reliant on the Blue Nile during these years. Now that the GERD is completed, and Egypt is faced with a fait accompli, the topic of discussion will shift from the conception of the dam to its future operation. Although Egypt allegedly threatened to blow up the GERD in the past, this is unlikely. Not only would its demolition contaminate the Nile’s water with debris and toxic waste, but the vast quantities of acutely released water would also flood Sudan, not to mention the potential for military retaliation and diplomatic isolation. Nonetheless, Egypt remains anxious about its future water supplies. The country’s current water share is approximately 560m3 per capita per year, which is already below the water poverty line of 1000m3 cap⁻¹ yr⁻¹. This is projected to drop further below the absolute water scarcity line of 500m3 cap⁻¹ yr⁻¹ by 2030. For this reason, Egypt wants assurances of sufficient downstream releases, particularly during periods of drought. Moreover, even before the GERD became operational, Egypt already relied on imports for 60–70 percent of its wheat consumption, highlighting its dependency in terms of food security. Before the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2022, Egypt received approximately 82 percent of its imports from Russia and Ukraine. Since then, it has looked to diversify its sources, though with limited success. Egyptian water and food security are therefore intrinsically tied together. So far, however, the two countries have not agreed on issues such as minimum flow, the definition of drought, and other water management affairs.

Future Scenario 1: The Posture-Precipitation Axis

Various scenarios can be framed along the axes of Ethiopia’s position and precipitation, all of which could seriously harm Egypt.

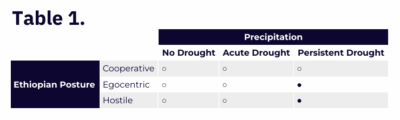

Table 1: The posture-precipitation axis and its potential for escalation

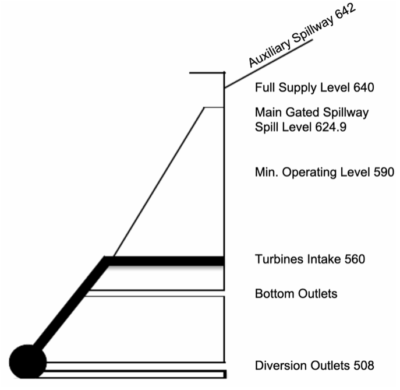

Research has suggested that under normal hydrological circumstances, the GERD will be able to operate optimally, meaning that it has a near-optimal hydraulic head, without any notable downstream repercussions. When Ethiopia displays a cooperative posture, when there is no drought, and under acute droughts that are not extreme, the chance of harming Egypt and subsequent escalation is estimated to be low, based on the precipitation axis alone. Under such conditions, the GERD reservoir is nearly full, with water levels ranging between 625 and 640 meters above sea level (asl) (see Figure 2). This enables optimal hydropower for Ethiopia while being unlikely to cause significant downstream water deficits, even under hostile intentions.

The reasons for this are:

- The primary objective of the GERD is power production, which requires a perpetual flow of water through its turbines. Reducing or stopping GERD activity is self-defeating and unlikely.

- Since both the GERD and AHD reservoirs are already near or at full capacity under the aforementioned conditions, there remains limited storage capacity for additional water inflow. During these scenarios, curtailing GERD operations would require discharging excess water through the dam’s spillways (see Figure 2). As this water flows downstream anyway, without producing power, it is in Ethiopia’s interest to sustain power generation by releasing volumes approximately equal to the reservoir’s inflow. This is irrespective of its posture.

- The reservoirs at both the GERD and the AHD have storage capacities exceeding the annual flow of the Nile. To hurt Egypt, the AHD basin would first have to be depleted, while the GERD reservoir would simultaneously have to be able to store a significant amount of extra water. Given arguments 1) and 2), this can only occur following a prolonged, multi-year drought.

Based on this, the most plausible scenario in which Egypt’s water security could be undermined is after a prolonged drought that leaves both the GERD and AHD basins nearly empty, combined with an egocentric or a hostile Ethiopian stance. Following this period, both reservoirs would require replenishment, raising critical questions about the sequencing and pace at which this process should occur. This scenario resembles the discussions that have taken place over the past few years, with the key difference that now, the AHD basin is (almost) empty too, increasing Ethiopia’s strategic leverage and the possibility of escalation. For Egypt, a worst-case scenario could unfold if, after such a drought, Ethiopia decided to prioritize filling the GERD reservoir over turbine activation. If the GERD reservoir drops below the dam’s minimal operating level of 590m asl (see Figure 2), Ethiopia might choose to re-establish power production capacity rather than ensuring a water supply to downstream countries. Above 590m asl, the generators can produce energy, with higher water levels resulting in greater hydroelectric yield. The decision then becomes striking a balance between refilling the reservoir to its optimal levels and instant energy production. Favoring the first over the second becomes more likely if Ethiopia determines that it is in its best interests or if it wishes to harm Egypt.

Figure 2: GERD cross-section, numbers in meters above sea level

Future Scenario 2: Extended Use, Population, and Climate Change

Another way Ethiopia could harm Egypt, outside of the posture-precipitation axis, is by initiating new dam projects or siphoning water from the GERD reservoir for consumptive use, such as irrigation for agriculture. Although this is not currently the case, pursuing such a course could have serious downstream consequences. Not only would it delay the flow of water, but the total quantity of the Blue Nile released downstream from the GERD would decrease as well. Given Ethiopia’s rapid population growth and limited current irrigation, this scenario remains plausible. Doing so would not necessarily infringe international law, however. Under customary international water law, reflected in instruments such as the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, Ethiopia holds the right to the equitable and reasonable use of transboundary waters, provided it avoids causing significant harm to downstream states and provided it cooperates with other riparian states.

Rising water demands in both countries, coupled with an increasing drought incidence, may lead to a legal paradox: The pursuit of equitable use by one side could inevitably cause significant harm to the other. If Ethiopia increases its water use, it could be viewed as violating these principles, particularly if Egypt’s water security is affected as a result. Ethiopia, in turn, might highlight its historical underutilization of the Nile’s waters relative to Egypt. It still only uses a fraction of the amount of water from the Nile that Egypt uses, despite having a larger population, and could assert its legitimate right to benefit from the river on par with other riparian states to justify an increase in consumptive use. New projects can accordingly be interpreted as steps towards a more equitable distribution of water, not as unfair.

Finally, even if the GERD’s output remains unchanged, Egypt’s population growth alone could intensify domestic water shortages and strain mutual perceptions, thereby reinforcing a zero-sum mindset.

Reflection

Much of the current friction stems from fears of worst-case scenarios, regardless of their likelihood. Such worries can themselves fuel conflict, consistent with the logic of defensive realism. Assuming that states mainly seek security for themselves, defensive actions by one state can be interpreted as a threat by another. In an international system characterized by anarchy, so goes defensive realism, Egypt cannot fully know Ethiopia’s true intentions, and its actions regarding valuable and finite resources, such as water, can trigger a security dilemma that leads to pre-emptive balancing behavior. Mistrust may arise even if everyone’s needs could, in theory, be satisfied. During and following periods of drought, any resulting water shortage in the AHD reservoir might be politically exploited by Egypt and attributed to the operation of the GERD, despite reductions in flow from other tributaries. In this way, a lower total volume of the Nile could be experienced in Egypt, even if the GERD adheres to agreed-upon release volumes, arousing suspicion and feeding the security dilemma.

Whichever scenario comes true, it is clear that the key to securing a workable future lies in overcoming historical, colonial, political, and cultural preconceptions through pragmatic water management and transparent, cooperative agreements. Unless cooperation is made open and trustworthy, Egypt will keep interpreting the existence and operation of the GERD as a loss in water security. A zero-harm scenario is increasingly unlikely due to factors beyond the GERD’s operation, mainly climate change and demographic pressure, and believing otherwise only hinders progress.

In the short term, the main risk is that both sides misread each other’s intentions. Reaching an accord on the GERD’s operation would reduce Egyptian concerns of Ethiopian self-interest and enable coordinated long-term responses to severe droughts. Transparent guidelines and information management also reduce the chance of natural events being wrongly interpreted, as not all water issues can be automatically attributed to the GERD. A sustainable agreement between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan would ideally contain consensus on political, legal, and technical clauses:

- The affirmation of customary international water law.

- The organization of dialogue forums for future Nile projects. A ban on all future upstream Nile projects, as proposed by Egypt, will not be accepted by Ethiopia.

- Definitions of terms such as average climate conditions, acute drought, prolonged drought, and drought recovery. These have to be based on hydrological data.

- A commitment to yearly flows of water under the climatic conditions stipulated above. Ethiopia will not sign a “fixed-flow treaty”: Under the argument of equitable and reasonable use, it will wish to release water in proportion to the annual hydrological conditions, discharging more during wet years and less under dry conditions. In contrast, Egypt has so far insisted on a fixed annual minimum release, irrespective of climatic conditions, to safeguard its dependence on Nile waters. This mismatch likely makes (4) the hardest point to resolve in reaching an agreement.

- Operational guidelines such as prioritizing basin refilling vs. GERD activity, hydrological thresholds of turbine activation, and their relation to (3) and (4). This will provide clarity and offer the possibility to prepare for the future.

- Transparency and an open data policy. The sharing of data should be done regularly and include: [1] GERD reservoir levels, [2] reservoir inflow and GERD outflow volumes, [3] precipitation forecasts, and [4] turbine performance metrics and operation schedules. These data are critical for ensuring compliance with the other points in the agreement and mutual trust.

- A periodical revision and, if necessary, modification of the agreement according to climate change, population growth, and other drivers of water demand.

- The establishment of a conflict resolution framework that specifies how disagreements will be settled. This could include setting up an independent arbitrage committee or a provision to appeal to a third, neutral party, and thereby mitigate mistrust.

Considering the countries’ divergent viewpoints, reaching binding agreements on these matters currently appears improbable. Nevertheless, the riparian countries should also address the structural factors driving regional water scarcity. These might include investments in desalination projects, reducing water loss (for example, by switching from flow irrigation to drip irrigation), recycling wastewater and agricultural drainage, and diversifying towards less water-intensive crops. Only by addressing all these issues can successful water governance be achieved in the Nile Basin.

Image: Traditional dancers perform during the inauguration of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) built along the Blue Nile in Guba, Benishangul-Gumuz region, Ethiopia, September 9, 2025. (REUTERS/ Tiksa Negeri)