A nation must think before it acts.

On October 20, 2025, a glitch at an Amazon Web Services (AWS) data center in northern Virginia triggered more than 6.5 million website outages, disrupting banking, logistics, and government operations. What appeared to be a software fault was, in fact, a warning about the material fragility of American power. Behind every “cloud” lies a mountain of hardware: transformers, copper cabling, rare earth magnets, and fiber optics. These materials anchor the digital infrastructure of the United States. When the supply chains for data centers and industry falter, compute slows, translating into degraded command-and-control capabilities for the US military.

In an era of strategic competition, digital reliability is deterrence. A single outage in a hyperscale facility can ripple across intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) networks, disrupting real-time operational efficiency. Data centers power the digital age and the associated server farms underpin everything from economic productivity to military decision-making and intelligence operations. Current data center infrastructure is composed of thousands of acres of servers, transformers, and cooling towers scattered across North America. However, these private-sector behemoths remain perilously exposed. In the digital era, failure to treat data and data centers as national defense assets is a strategic blind spot.

The dynamics of deterrence have evolved in the 21st century. Previously, power projection relied on fuel and steel; currently, it relies on megawatts and computational throughput. The physical foundations of the cloud, including transformers, rare earth elements, and copper, are as essential to national security capabilities as shipyards and automobile assembly lines previously were.

The same materials that make fighter jets, missiles, and satellites are what make artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing, cyber warfare, and command and control possible. When supply chains for these materials falter, such as through Chinese export controls on certain minerals and rare earths, or when power grid bottlenecks delay new facilities, the US military’s ability to process and act on information stalls. A targeted mineral embargo against the United States could undermine the infrastructure that supports military networks for collection and dissemination of ISR information.

For policymakers, the issue is that data centers are dual use. The Pentagon’s Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability (JWCC) and Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) networks utilize the same commercial power and server backbones that serve industry. A disruption in copper, transformer steel, or photonic components slows both sectors simultaneously. The boundary between civilian compute and military command has effectively vanished; resilience in one now requires resilience in the other.

Cloud outages have a major impact on the economy, critical infrastructure, and military operations, meaning the security and the functioning of these data centers are a major national security issue. This article traces the hidden linkage between data centers, component materials, and military readiness. It quantifies the physical footprint of compute infrastructure and examines the emerging vulnerabilities in supply chains and construction timelines before outlining concrete policy steps to harden the ability of US digital computing power.

The Mathematics of Data Centers: Power, Materials, and Build Cycles

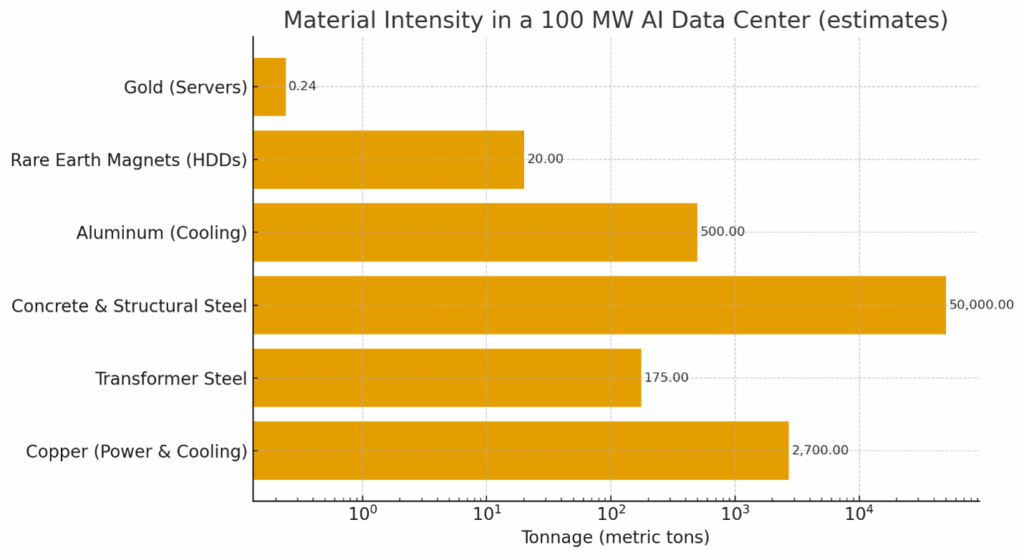

Compute power may seem infinite, but its physical limits are constrained by materials and infrastructure. Building a single 100-megawatt AI-enabled data center—a power requirement on par with a mid-sized American city like Dayton, Ohio—has massive physical requirements. Each site needs about 2,700 tons of copper for cabling and busbars, 150 to 200 tons of transformer-grade steel, and more than 50,000 tons of concrete and structural steel for the shell. Even the smallest components carry strategic weight: rare-earth magnets inside hard-disk drives, gold in server connectors, and indium phosphide in optical transceivers. These materials form America’s compute base (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Material Intensity in a 100 MW AI Data Center (estimates)

The estimates for material tonnage are a synthesis of data from multiple sources, including the International Copper Association (2022) for copper requirements, the Department of Energy (2024) for transformer steel, and Arup (2022) for other embodied materials. Figures for rare earth elements and gold are based on component-level mineral data from the USGS (2024).

Every new data center build amplifies these demands. Their construction has already become one of the world’s fastest-growing industrial sectors for copper, aluminum, and specialized steels. Yet production of critical raw materials remains concentrated in a handful of unstable and/or authoritarian countries. The mathematics are unforgiving: Small shortages in transformer steel or copper can delay data center completion by years, with cascading effects on compute availability across both the civilian economy and defense networks.

This situation reflects the limitations that previously characterized naval logistics and fuel supply chains in the 20th century. In this context, computation has become a new form of logistics: Instead of moving oil to the front, it moves information to the decision-maker. And like oil, its flow depends on extraction, refining, and transport chains that are slow, exposed, and politically entangled.

Power requirements amplify the problem. Each megawatt of data center load also requires an investment in grid capacity through substations, high-voltage lines, and cooling systems, which depend on the same constrained material inputs.

Meanwhile, China’s 2024 National Computing Network Initiative plans over 300 new dual-use data centers that explicitly combine commercial and defense functions. Conversely, the expansion of computing in the United States is constrained by transformer shortages, permitting delays, and utility congestion. The inequality lies in hardware: Those who govern material throughput dictate digital speed. This disparity poses a sustained threat to information supremacy.

The American economy and military are racing to deploy AI, advanced analytics, and global sensor networks, yet current bottlenecks reside in the alloys. Each layer of digital acceleration adds an industrial burden that compounds over time. Rather than pursuing an endless build-up of capacity, the United States must also innovate its way out of material dependence. Advances in chip architecture, photonics integration, and compute efficiency, like domain-specific accelerators and co-packaged optics, can reduce the physical footprint of compute. Investing in efficiency at the transistor and algorithm level can stretch limited materials far further than adding another data hall.

Emerging Vulnerabilities: Grid, Transformers, and Mineral Bottlenecks

The most advanced command-and-control systems in the world still depend on transformers, specialized metals, and high-purity optics that each have globalized supply chains with slow replacement cycles. What once seemed like a commercial challenge is now a question of national security. A grid failure or material shortage that halts data center construction can lead to delays in the flow of intelligence and targeting data to combatant commands.

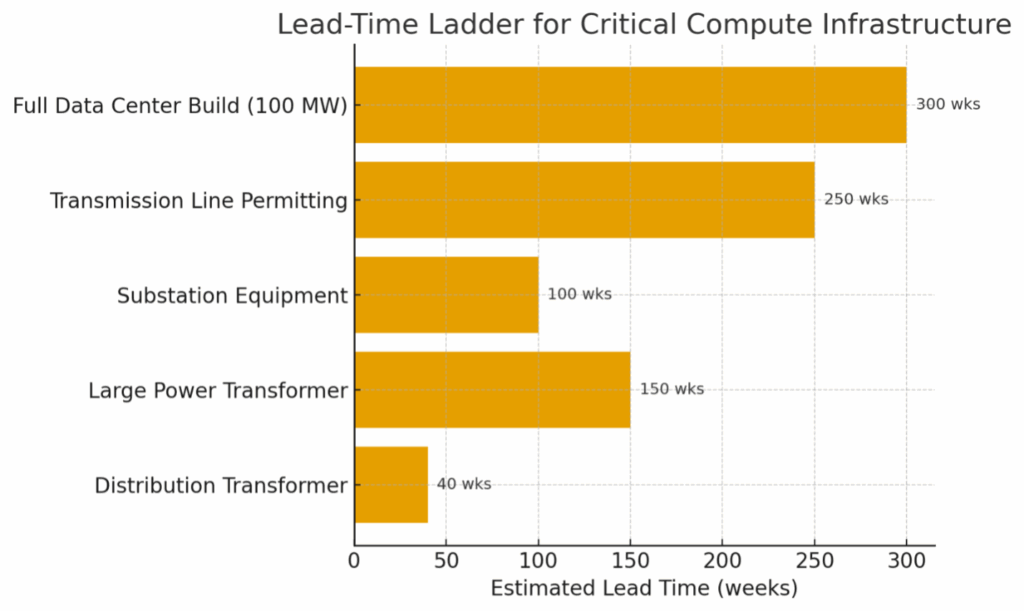

Transformer availability sits at the center of this risk. Rising demand, aging manufacturing equipment, and global concentration of electrical-steel supply have extended delivery schedules from under a year to more than four (see Figure 2). The same pattern holds for high-voltage substation components and electrical steel, where China, India, and Japan dominate supply. This creates an invisible drag on digital expansion. Even if America builds new compute clusters, the energy infrastructure that powers them cannot keep pace.

Figure 2. Lead-Time Ladder for Critical Compute Infrastructure

The estimates for lead times are derived from an aggregation of data from the US Department of Energy (DOE) reports in 2023 and 2024, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) in 2024, and private-sector analyses, including those from EPRI, the Uptime Institute, and McKinsey in 2023. The figures represent median durations and are subject to variation based on capacity and permitting jurisdiction.

These constraints spill directly into defense readiness. The recent US Department of Energy Grid Supply Chain Review cautions that the transformer backlog, extending for many years, is causing systemic delays in both commercial and defense programs. The 2021 Texas power crisis illustrated how grid instability can lead to widespread digital blackouts. Should such a disruption coincide with cyber or kinetic attacks, command-and-control systems dependent on commercial clouds may fail during crucial mobilization phases. In contrast, China’s State Grid Corporation manages dual-purpose “computing and command” corridors that ensure uninterrupted power supply for military intelligence fusion centers. The disparity is stark: US computing relies on market logistics, but China’s computing is regarded as national defense infrastructure.

Equally concerning is the geopolitical geography of these critical materials. China produces over 70 percent of the world’s transformer steel, refines most rare-earth elements, and dominates the wafer-level photonics used in optical transceivers. Any export restriction or embargo could throttle global build-out of hyperscale compute, giving Beijing a lever over both economic and military networks. Even friendly bottlenecks matter: The United States has only two domestic transformer plants capable of producing the large units needed for defense-critical data centers. The combination of long industrial lead times and concentrated supply creates a slow-burn crisis. Power, not processing speed, may determine who holds the advantage in digital-age warfare.

From Compute to Combat Power: Why the Cloud Is a Warfighting Enabler

Modern warfighting runs on compute. Every mission, from satellite intelligence and maritime surveillance to predictive maintenance and AI-enabled targeting, depends on data flowing through vast server farms and secure fiber links. These networks form to support military and intelligence actions across Joint All Domain Operations (JADO). When that data flow slows, the tempo of sensing, deciding, and acting slows with it. Compute latency means combat latency.

Decision cycles that previously depended on human analysis increasingly rely on distributed computing infrastructures. The more rapidly a nation can receive, communicate, and integrate sensor data, the more credible its deterrent stance becomes. Throughout the conflict in Ukraine, distributed cloud architectures were pivotal. When Russian missile strikes targeted Ukraine’s command infrastructure, Kyiv rapidly migrated intelligence and targeting data to cloud-based systems. That shift allowed operations to continue with minimal disruption, preserving pace and decision speed even under attack. Compute resilience enabled continuity of operations.

Compute is the new logistics for 21st-century warfare. It moves information instead of fuel, but its vulnerabilities are strikingly similar: limited surge capacity, globalized dependencies, and long resupply timelines. The United States once maintained strategic stockpiles of oil and munitions to ensure freedom of action in crisis. Today it must think the same way about the transformers, rare-earth magnets, and photonic wafers that are needed for a data server farm. Each is a “just-in-time” component that underwrites digital-age war.

Faster kill chains require the compute power hidden in the algorithms and AI at physical server farms, which depend on uninterrupted access to power, bandwidth, and data. An adversary that can choke these inputs, either through cyber-attack, export control, or sabotage, can slow US decision-making without firing a shot. Hence, protecting compute infrastructure is a strategic imperative that can hinder or enable US military operations in crisis or conflict.

Ultimately, superiority in warfighting increasingly depends on data that can be processed, transmitted, and acted upon faster than the enemy. Compute is combat power, and the materials that sustain it are the new munitions. Securing this edge means the United States must defend and sustain the factories, foundries, and substations that make data centers function.

Six Steps to Improve US Compute Power and Resilience

We highlight six steps needed to align industrial tools and defense planning approaches to preserve the US economy and military warfighting abilities.

First, Washington must designate and protect National Compute Nodes, data center clusters whose function is critical to both economic stability and military readiness. These facilities should receive priority access to transformers, fiber routes, and electrical power, along with hardened redundancy and physical defenses comparable to strategic ports and air bases. Compute should be viewed as a form of infrastructure sovereignty and defended accordingly. Regional diversification of data centers would ensure resilience, so that no single natural disaster, cyber-attack, or grid failure can paralyze national decision-making.

Second, the United States must accelerate grid and transformer capacity. Transformer lead times now exceed two years, delaying both commercial and defense projects. The Department of Energy should coordinate with industry to co-fund new electrical-steel and transformer manufacturing plants, establish a strategic reserve of key grid components, and expedite permitting for defense-critical substations. Every week of delay in electrical power delivery translates into slower compute growth, meaning slower economic growth and military command and control.

Third, policymakers must secure materials and photonics supply chains. Copper, transformer steel, rare-earth magnets, and indium-phosphide wafers underpin the entire data center ecosystem. Yet these midstream refining and finishing processes are concentrated in China. Extending Defense Production Act authorities, allied sourcing partnerships, and industrial incentives to these materials will reduce foreign dependency. Recycling and circular-economy programs can supplement domestic supply, but they cannot substitute for new refining and alloy capacity on US soil.

Fourth, Washington needs to deploy targeted industrial tools to rebuild the “missing middle” of manufacturing that connects raw materials to finished components. CHIPS Act styled incentives should expand to include magnet alloys, capacitor powders, optical connectors, and power electronics. These investments are modest compared to the strategic cost of supply-chain ruptures in wartime; plus, they yield long-term dividends in jobs, technology, and resilience across the defense industrial base.

Fifth, compute resilience must become an element of defense planning. Combatant commands should wargame scenarios in which data centers or regional grids are degraded or disrupted. Exercises should test backup compute, power rerouting, and data prioritization under contested conditions, just as logistics drills stress munitions and fuel. Deterrence depends on speed of response, and the assurance that speed can be sustained when data systems are strained or attacked.

Finally, the United States must align its electrical power grid with national security. Data center reliability depends on uninterrupted energy. This can mean small modular reactors, advanced geothermal plants, or contracted renewables backed by large-scale storage. The Pentagon should treat megawatts as munitions: finite, strategic, and vital to operations. Hardening that power base completes the loop between energy, compute, and combat power. It ensures the US military can sense, decide, and act faster than an adversary.

Emerging sensor technologies will amplify these compute demands. Quantum magnetometers, gravimeters, and other precision sensors will generate unprecedented data volumes, collapsing the decision window in future conflicts. Quantum sensing may make the invisible visible, but only if backed by resilient compute infrastructure capable of processing those signals in real time. Without secure power and stable data centers, quantum advantages are lost to immense noise these systems will generate.

By locking power, materials, and manufacturing into a single resilience plan, the United States can preserve its edge economically and militarily. Securing transformers, materials, and megawatts is as vital as maintaining aircraft or missiles. Washington must invest in the industrial base of intelligence—the physical architecture of cognition that turns information into strategy and compute into combat power.

American competitiveness will be built from silicon and electricity. Future success depends on every algorithm, satellite, soldier, and weapon system operating with an uninterrupted cloud. The chemistry of modern war has changed: It now runs on materials, minerals, and megawatts.

Image: