A nation must think before it acts.

Students must understand the multi-faceted nature of the Cold War between the US and USSR

Footnotes is the bulletin of FPRI’s Marvin Wachman Center for Civic and International Literacy. Essays published here are designed in particular for teachers and students and are often drawn from the lectures at our nationally recognized Butcher History Institute for Teachers.

Deficiencies in Cold War Knowledge by U.S. Students

The Cold War (1947-1991) is not only an important topic in world and U.S. History, but it also offers an excellent opportunity for students to become more economically literate through understanding the consequences of the most extensive socialist experiments in history. A better understanding of the Cold War fosters insights into the incentive structures of socialism in its “democratic” forms as well as some understanding into its seemingly eternal appeal to large portions of the population. Students who systematically study this seminal event in world and American History must consider important ideological and moral questions that were foundational in the Cold War. What follows is a special segment on the Cold War that I have modified and implemented in my Secondary School History and Social Science Methods classes throughout the last several years. I recently presented this instructional segment to high school and undergraduate instructors at an international economic education conference and in a teacher institute.[1]

My interest in incorporating content about the Cold War into a social studies methods course began six years ago after hearing a provocative and powerful March 5, 2003 lecture by Alan Kors entitled “Is This Still the Age of Socialism?” It is archived in the Intercollegiate Studies Institute lecture series. Professor Kors discussed two topics that particularly interested me. First, Kors lamented the failure of the U.S. and other liberal democracies to intensely denounce communist governments at the end of the Cold War—in stark contrast to the historical and contemporary Western condemnation of Nazism. This relative silence on the part of liberal democracies regarding communist atrocities ignores the fact that totalitarian communist regimes killed many more people than Hitler’s Germany; communist regimes killed roughly 100 million people compared to an estimated 25 million deaths caused by Nazis.[2] The second topic that caught my attention was Kors’ assertion that most contemporary high school and university students perceive the Cold War as primarily a nuclear arms race between the super powers rather than an event deeply rooted in profoundly contrasting views and beliefs about human action.

Every semester at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, I am the primary instructor for the secondary history education and social science methods courses. The majority of my students plan to become history teachers, and the 90% of students who aspire to be high school teachers must take 30 semester hours of history courses, which they usually complete before they enroll in my class. Intrigued by Kors’ second assertion, I began asking students in the class to define briefly the Cold War and added a short answer question on the Cold War to a history knowledge diagnostic assessment that I administer during the first class. Both the oral and written answers that I have received from students corroborate Kors’ assertion. A few students, usually aspiring middle school teachers who have taken a small number of history courses, are unfamiliar with the term “Cold War.” Approximately 90% of remaining students stress the nuclear arms race between the super powers and their allies. Economic systems, or contrasting ideas about ideology, morality, and human nature, are only occasionally included in student written definitions of the Cold War. In response, I developed this special segment on the Cold War.

My overarching goal for the special segment is to help students understand how the most grandiose experiments with socialism in world history impacted the lives of people in communist nations. What follows are brief descriptions of links, methods, and materials I employ in the Cold War special segment. The total amount of time in my class devoted to learning about the Cold War includes approximately five hours of in-class activities which comprise portions of four separate two and one half hour night classes (my class meets once a week, and several separate topics are addressed in each class meeting). Students study the Cold War as a part of the “Teaching Modern World History” portion of the course. There are many sources that can help students learn more about the Cold War, but in this class, I use three broad sources for which students are responsible for reading or viewing inside and outside the class in order to increase their contextual knowledge of economics, post-World War II events in Asia, and the beginning of the Cold War in Europe: Common Sense Economics, Modern Chinese History, and Winston Churchill (documentary).[3]

The introductory Cold War classroom activity is a distribution of the one page basic handout I created that appears below. I make brief remarks in class about most of the items on the handout and answer questions. The purpose of the handout is the provision of context about Communism and the Cold War for students; this context helps them better understand the Kors lecture they view as homework and subsequently write a two-page paper on the video for the next class.

Handout—Modern World History: What Social Studies Teachers Should Know about Communism and the Cold War

Your next short paper is on the Alan Kors video lecture “Is This Still the Age of Socialism?”

You can skip the introduction if you so choose and begin the video at approximately 5 minutes. In order to provide context so that you can get the most out of the powerful lecture, please read what follows first:

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels developed the theory of Communism in the mid-19th century while writing in the United Kingdom.[4]

- Socialism is an economic system that features public (government) ownership and production of goods and services. Communism is a form of socialism based upon the notion that economic and class relations exclusively determine the course of history. It is revolutionary in that its proponents argue they are working toward a classless society with minimal government where everyone works together and has enough to meet his or her needs. The official ideology of communism includes atheism although some communists are not atheists. Communists are also called Marxists. The terms are synonyms.

- Beginning in 1917, Russia was the first country ever to attempt to implement communism. The Soviet Union (USSR)—the name of the Russian Communist government—lasted from 1917 to 1991.

- Every communist government that has existed for any length of time abolished rival political parties, persecuted political opponents, and implemented, if powerful enough, a totalitarian government during the so-called “dictatorship of the proletariat” (worker) stage. In his lecture, Kors calls communism “consequential socialism.”

- Marxist governments that still exist in North Korea and Africa continue to feature a socialist economic system where there is no or very little private ownership.

- From 1947 until 1991, the U.S. and its allies and the USSR, its satellite European states, and its allies engaged in a worldwide struggle for dominance. Although some historians and observers argue that there was moral equivalence between the two sides, Alan Kors and other sources show that communist dictatorships were responsible for killing nearly 100 million of their own citizens. At least fifty million (conservative estimate) people died in Mao’s Communist China. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the West, despite being involved in proxy wars, committed no atrocities that came anywhere near the scale of what occurred in communist countries.

- The plight of Eastern Europe was particularly poignant. Most of these nations were forced by the USSR to become part of the Soviet Empire. During the Cold War, these countries were referred to as the Iron Curtain, a term Winston Churchill coined.

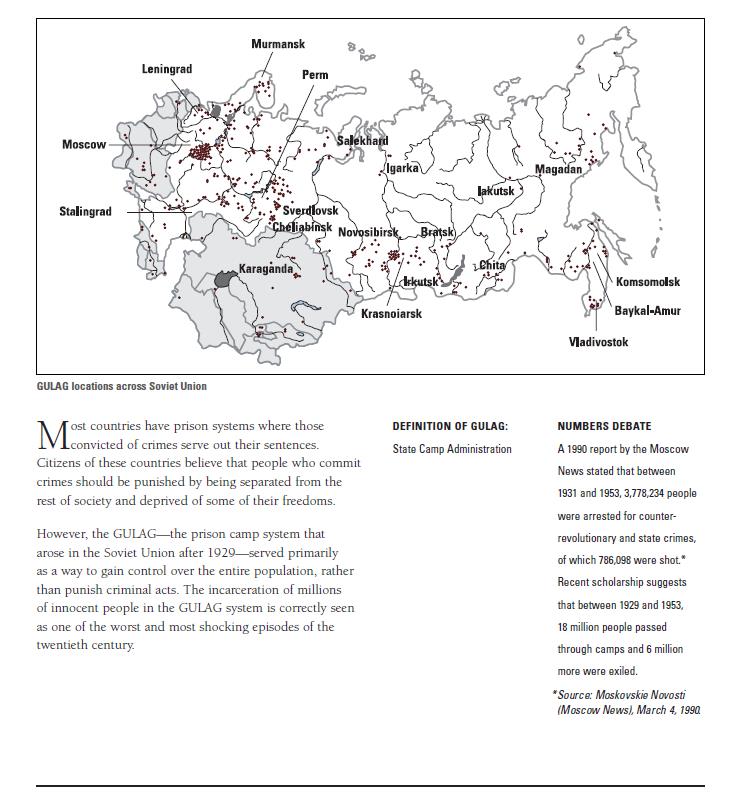

- Another term you will hear in the Kors lecture is “Gulag,” which is the Russian term for prison camp. Gulags still exist today in Communist North Korea.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is a vivid account of life in a Gulag. The novel is short and widely used. There is a movie based on it. Two other famous anti-communist novels are George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm.

- Communism and the Cold War are not only important in modern world history, but also important for civic and economic literacy. Because communism and even democratic socialism are so theoretically appealing, they always have adherents.

Understanding the Failure of Mao’s China

The second Cold War classroom activity that takes place on the same evening, focuses upon China’s 1958-1962 Great Leap Forward. Students watch a 22 minute Great Leap Forward excerpt from the segment entitled “The Mao Years” from the four part 2007 documentary China: A Century of Revolution. Part of perhaps the best documentary ever produced on 20th century China, the segment on the Great Leap Forward features candid interviews in China with academics, peasants, workers, Mao’s former physician, and others who lived through these tumultuous years. Students have context for the documentary since Mao’s Great Leap Forward was included in the assigned reading and paper from the Modern Chinese History book referenced earlier. At this point in the course, students have also read Parts I and II of Common Sense Economics, so they understand the concept of secondary effects/unintended consequences and comprehend how attempted government management of an economy (especially in totalitarian communism) makes political rather than economic considerations dominant.

For readers who are unfamiliar with The Great Leap Forward (Mao’s Second 5 Year Plan), it was an attempt by Mao to utilize half a billion men, women, and children residing on large agricultural communes throughout China in order to both increase food production and enhance industrial output in electricity, coal, and, especially, steel. Mao believed that effort rather than expertise would result in achieving these two goals. Party cadres were fearful of not meeting agricultural and industrial quotas, so many local and midlevel party leaders exaggerated production figures and reported higher agricultural yields than actually achieved. Additionally, the steel produced in backyard furnaces throughout China was useless. The central government, which planned to feed urban Chinese with “surplus” agricultural produce, took food supplies from the countryside based upon the phony numbers reported by cadres and transported grain and rice to the cities leaving peasants without enough food. The massive unintended consequences of the Great Leap Forward were the primary reasons for the starvation of approximately 30 million Chinese peasants, the largest man-made famine in world history. Students, most of whom know nothing about this event, are visibly moved by the accounts in the documentary by survivors discussing how family members starved. Students also more easily grasp the potential for chaos that is possible when economic incentives are replaced with politicization.[5]

It is worth noting—and I do so at the conclusion of the Great Leap Forward segment—that during the 20th century, at least four communist regimes in addition to China (USSR 1928-1932, Ethiopia 1970s-1980s, Cambodia 1975-1978, and North Korea 1990s) were responsible for perpetrating man-made famines.[6]

Barbarism and a “Helping Hand”: The Gulags and the Marshall Plan

In the following class, the focus shifts to the USSR and Europe. For approximately 20 minutes, we have a class discussion on the papers that students wrote on the Alan Kors lecture. Kors vividly describes how totalitarian socialist policies resulted in millions of deaths and makes a powerful argument that even many journalists, novelists, public intellectuals, and politicians in Europe and the U.S. who condemned Soviet Communism’s excesses never explicitly made connections between economic policies common to all socialist systems. These opinion-molders also, according to Kors, often downplayed the Cold War as a struggle between proponents of two economic systems. In the same class, I introduce Gulag: Soviet Prison Camps and Their Legacy, a 59 page unit for high school instructors and teachers developed by scholars at Harvard University’s National Resource Center for Russian, East European and Central Asian Studies. The unit, designed for three, one hour high school class periods (with homework assignments), is highly informative and includes maps, photographs, Gulag survivor accounts, and even polls about post-Communist Russians’ surprisingly mixed opinions about the Gulags and Joseph Stalin, the man who was responsible for their major expansion.

We spend approximately an hour (two 30 minute segments in two separate classes) having students work through Day 1 of the unit which includes a concise description and map of the locations of Gulags, a timeline, a biographical vignette of Stalin, descriptions of three campaigns against “Enemies of the People,” a description of the types of prisons that were created, a narrative on what categories of prisoners were sent to the Gulags, and the economic and social effects of the mass arrests on the spouses and children of incarcerated individuals. Students learn that simple envy on the part of a neighbor, especially in the Stalin years, could easily result in an individual being sent to a Gulag.

The Gulags were intended in part to incarcerate real and imagined political prisoners, but many of the large prison populations were used for major economic projects. In-class work with the unit includes a case study of the massive 1931-33 White Sea Canal project connecting two inland water ways that utilized 175,000 prisoners using primitive hand tools to construct the canal. At least 25,000 prisoners died during the construction of the canal, often because of insufficient food supplies, subzero temperatures, and inadequate housing. Instead of utilizing steel and cement to construct the 141 miles of waterways and the 19 locks, prisoners had to use sand, rocks, and wood. They completed construction on the canal in a short period of time, and government officials used its quick construction as a pro-Stalin propaganda tool; party officials claimed that the camps and the labor rehabilitated the prisoners, and the canal would result in substantial economic gains for the USSR. However, the poorly built canal was too narrow and shallow. Barges could use it only rarely, and it was impossible for passenger ships or submarines to use. The last topic addressed on Day 1 of the unit is “Camps as Economic Failures.” I have students spend approximately 8 minutes reading this section of the unit in class and we then discuss the economics and politics of the gulag-forced labor system. Although there were exceptions, such as Siberian Gold Mining, prison labor did not make a substantial contribution to the economy. Upon Stalin’s death, the process of closing camps began because of their (then publicized) economic inefficiency.[7] A graphic from Day 1 of the Gulag curriculum guide is included in this article to illustrate the high quality of the Gulag unit.

The Marshall Plan is a topical focus for 30 minutes in one of my Cold War-related classes in conjunction with the Gulag material. Students read “The Marshall Plan for Rebuilding Western Europe” from Bill of Rights in Action (Constitutional Rights Foundation). Bill of Rights in Action (BORIA), justifiably highly respected among high school teachers, is a quarterly newsletter specifically designed for history and government classrooms. Each issue consists of 4-5 page articles on three separate topics. Treatment of content is accurate, objective, written on a high school reading level, and each reading is accompanied by discussion questions and often additional activities. Most BORIAs, including the one cited in the narrative, are archived and available at no charge.

I augment the newsletter through a 5-6 minute lecture based upon excerpts from primary source material included in David McCullough’s acclaimed 1992 biography Truman. Students learn about Europe’s post-war devastation along with George Kennan’s, Dean Acheson’s, and George Marshall’s realization by 1947 of Stalin’s unwillingness to negotiate regarding a divided Germany or regarding the Eastern European nations the USSR then controlled. The BORIA reading informs students of the Truman Administration’s determination to convince both political parties and the American public that a massive European economic reconstruction program could serve to check the further spread of communism in Europe and elsewhere. In April 1948, Congress passed the “Economic Cooperation Act of 1948,” known commonly as the Marshall Plan. From 1948-1951, it provided over $13 billion (USD) in aid to 14 Western European nations including the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The language in the act indicated that the major objectives of the Marshall Plan were to ensure “individual liberty, free institutions, and sound economic conditions.”[8] Students discuss both the intended and unintended consequences of this historic American economic reconstruction initiative.

Excerpt from “Gulag: Soviet Prison Camps and Their Legacy,” pg. 1

Khmer Rouge Genocide

During the same class that includes the Marshall Plan, students spend 30 minutes on the most radical communist experiment in world history, the 1975-1979 Khmer Rouge Genocidal Regime in Cambodia. The Yale University Cambodian Genocide Program estimates that the Khmer Rouge, under the leadership of Pol Pot, killed about 1.7 million people, roughly 21% of the nation’s population. Upon the overthrow of the Khmer Republic in 1975, the Khmer Rouge (the unofficial name for the communist faction that gained power; the government’s formal name was Democratic Kampuchea) in an attempt to create an unprecedented socialism, quickly depopulated Phnom Penh and other cities, abolished money, and classified the populations. The rural proletariat was generally protected. Anyone else who could not flee and was not a member of the Kampuchean Communist Party faced great peril. Former city dwellers, especially people who were not working class, ethnic minorities including Vietnamese (despite North Viet Nam’s communist ideology), and anyone who was defined as a dissident, were subject to execution, starvation, imprisonment, and torture. Thanks to the 2015 award-winning online 18 minute documentary My Cambodia, available for no cost, students can gain a vivid and accurate impression of this horror. The narrator, now a professor at the University of California: Berkeley, revisits the nation that she was fortunate enough to escape in the 1970s, and much of the footage is devoted to the most infamous of the Khmer Rouge Prisons and to the “Killing Fields” where mass executions occurred. My students quickly realize from the documentary that their residences and/or class level could quite easily mean death during the Khmer Rouge years.

Time does not permit an extensive treatment of this topic in a survey course, but in a few minutes during this segment, I explain that in its effort to fight hostile Vietnamese and Cambodians inside Cambodia during the Vietnam War, the U.S. inadvertently created a situation where much of the rural population supported the Khmer Rouge in the civil war that it eventually won.[9]

Literature and Government Tyranny: Friedrich Hayek and Aleksander Solzhenitsyn

Excerpts from internationally-famous economist Friedrich Hayek’s non-fiction classic, The Road to Serfdom and Aleksander Solzhenitsyn’s novel, In the First Circle, constitute the final activity in the Cold War segment. These two opponents of totalitarian communism articulate perhaps the most powerful moral cases against socialism, and in Solzhenitsyn’s case, particularly communism; these cases resonate with students if they have the context that hopefully the prior activities provide.

Thirty minutes introducing and discussing excerpts from each author with students can help to illuminate the moral degradation that is always a potent possibility when government dominates or controls both the economy and society. Moral depravity is always possible in human action regardless of what ideological and economic systems dominate, but Hayek’s “Why the Worst Always Get on Top” illustrates how socialism is conducive to the ascent of evil tyrants:

First, the higher the education and intelligence of individuals become, the more their tastes and views are differentiated. If we wish to find a high degree of uniformity in outlook, we have to descend the regions of lower moral and intellectual standards where the more primitive instincts prevail. This does not mean that the majority of people have low moral standards; it merely means that the largest group of people whose values are very similar are the people with low standards.

Second, since this group is not large enough to give sufficient weight to the leader’s endeavors, he will have to increase their numbers by converting more to the same simple creed. He must gain the support of the docile and gullible, who have no strong convictions of their own but are ready to accept a ready-made system of values if it is only drummed into their ears sufficiently loudly and frequently. It will be those whose vague and imperfectly formed ideas are easily swayed and whose passions and emotions are readily aroused who will thus swell the ranks of the totalitarian party.

Third, to weld together a closely coherent body of supporters, the leader must appeal to a common human weakness. It seems to be easier for people to agree on a negative program–on the hatred of an enemy, on the envy of the better off–than on any positive task.[10]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who spent years in the Gulags, captures the “worst” in the novel In the First Circle. Students are first given brief context on Solzhenitsyn and a summary of the novel for the excerpt on Stalin that follows. A then-loyal communist and decorated war hero, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by Smersch, the Soviet Spy agency, and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp in February 1945. The evidence that incriminated him, according to the authorities, was his disrespect of Stalin. The evidence was a letter to a school friend in which Solzhenitsyn referred to Stalin as “the man with the mustache.”

After stays in several prisons and labor camps doing menial labor in grueling conditions, in July 1947, Solzhenitsyn, a university-trained mathematician, was moved to Special Prison No. 16. The special prison was a sharashka; this category of prisons was meant especially for highly trained scientists who were forced to do advanced scientific research. Inmates had some privileges and better food. Solzhenitsyn’s assignment was to work on an electronic voice recognition project with applications for coding messages and identifying leaks. Because politics always trumped expertise in the prison, Solzhenitsyn was banished to a remote camp in Kazakhstan doing hard labor again because he criticized the scientific abilities of his non-prisoner Colonel who headed the project.[11]

In the First Circle is based upon Solzhenitsyn’s three years in Special Prison No. 16. In one chapter on Stalin, the dictator muses on his “four rules for greatness:”

It is rightly said that we reach maturity at forty. Only then do we finally understand how to live and behave. Only then did Stalin become aware of his greatest strength: the power of the unspoken verdict. Your mind is made up, but the person whose head depends on our decision must not learn it too soon. Time enough for that when his head rolls! Another strength was his habit of disbelieving what others said and attaching no importance to his own words. Say not what you mean to do (you may not know it until the moment comes) but what puts the other person at ease. A third rule for the strong man is never to forgive anyone who betrays you, and if your teeth are in someone’s throat never let go, though the sun rises in the west and portents appear in the heavens. A fourth rule for the strong man is not to rely on theory. Theory never helped anyone; you can always produce some sort of theoretical justification after the event. What you must always keep in mind is what fellow traveler you need for the present and at which milestone you must part company.[12]

Stalin’s approach to human interactions epitomizes the personality type of the “worst,” and research on totalitarian socialist leaders consistently confirms Hayek’s assertion. It is not enough to simply criticize totalitarian socialism because of its manifest economic failures. The separation of moral and ideological concerns from critiques of socialism makes these critiques much less effective. Students deserve a more holistic approach that fosters understanding of the political, economic, and, perhaps most important, moral consequences of the Cold War and the ideology and economic systems of totalitarian socialist nations.

Lessons for Students

An organized introduction to the Cold War utilizing a variety of print and video sources offers profound, educational benefits for students.

A foundational lesson from learning about the Cold War is that ideologies have massive consequences. No systematic view of human history, society, and action “completely works” when assessed in light of historical events, but the historical evidence regarding Marxist governments is powerful and evidential. In totalitarian socialist systems, ordinary people are deprived of most freedoms and much more likely to be imprisoned or killed by their governments than is the case with citizens fortunate enough to live in liberal democracies—even if they reside in partially-free or authoritarian societies. A basic understanding of the Cold War is at one level a “wake up” call for many students who previously had no clue that a monumental clash of contrasting ideas about human nature and action constituted the foundation of a struggle that lasted well over three decades.

A second lesson is that communist and socialist economies do not work well because political incentives are much more likely to trump economic incentives in critical investment, resource allocation, and production decisions. The disasters caused by the “Great Leap Forward” and the attempt to use the Gulags to attain economic objectives in the Soviet Union are just two of many examples that compellingly prove the point; the 1928-1932 famines that occurred because of the first USSR Five Year Plan, the 1970s-1980s famines in Ethiopia, and the North Korean famines of the 1990s resulted in the deaths of millions of people, primarily because of government-forced collectivization policies. Even less oppressive socialist governments intentionally or inadvertently impose incentive systems that do not foster the efficient and ample production of goods and services, spur innovation, create monetary and fiscal stability, or generate meaningful employment that increases human self-worth and stimulates individual energy and optimism to the extent that is the case in economies with large market sectors.

Finally, organized religions throughout the world have established ethical and moral structures that have been an integral part of human life. Marx spurned religion as reactionary, and communist governments, beginning with establishment of the USSR, have consistently and actively persecuted a variety of religions by oppressing, imprisoning, and killing millions of faithful adherents. The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a Washington-based U.S. non-profit organization established by a 1992 bipartisan act of Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton, extensively documents much of the history of communist attacks upon organized religion.

Lucien Ellington thanks Nancy Asplund and Jeff Melnik for their assistance in the development of this manuscript and Thomas Shattuck and Ron Granieri at FPRI for their suggestions.

Notes

[1] An earlier version of this article was presented as a paper at the 41st Meeting of The Association for Private Enterprise Education in Las Vegas, Nevada on April 4th 2016.

[2] Stephane Courtois, Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Panne, Andrzej Paczkowsi, Karel Bartosek and Jean-Louis Margolin. The Black Book of Communism. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999): 4.

[3] James D. Gwartney, Richard L. Stroup, Dwight R. Lee, Tawni H. Ferrarini. Common Sense Economics (Revised), (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010); David Kenley. Modern Chinese History. (Ann Arbor: the Association for Asian Studies, 2012); and Winston Churchill presented by Martin Gilbert (New York: A&E Television Networks, 2003), DVD.

[4] Communism’s foundational text is Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto (1848). Although readers can find primary source excerpts from the pronouncements of communist leaders and governments in the various recommended sources included in this article, specific regimes emphasized various aspects of Marxism depending upon historical circumstances, varying cultures, and domestic and international policy circumstances. Nevertheless, the ideological basis of communism was and continues to be The Communist Manifesto. Reading this work that was written as a political tract is the best way to gain a basic understanding of the communist theory. This short text is universally available in libraries and less than 50 pages depending upon the publisher. A PDF version is available online.

[5] Clayton D. Brown, “China’s Great Leap Forward,” Education About Asia 17, no. 3 (2012): 29-34. https://aas2.asian-studies.org/EAA/EAA-Archives/17/3/1073.pdf. This article, which I have sometimes used in the course I am describing and often utilized in teacher professional development programs, is in my opinion, the best published short introduction to the Great Leap Forward.

[6] Michael J. Seth, “North Korea’s 1990s Famine in Historical Perspective,” Education About Asia 16, no. 3 (2011): 24-28. https://aas2.asian-studies.org/EAA/EAA-Archives/16/3/1156.pdf.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Constitutional Rights Foundation. “The Marshall Plan for Rebuilding Western Europe.” Bill of Rights in Action 20, no. 3. Summer 2004. https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-20-3-a-the-marshall-plan-for-rebuilding-western-europe.html (accessed 3 24, 2016): under “The Marshall Plan in Action,” para. 1.

[9] For an article by a Cambodian academic that includes a succinct context for the events before 1975 but focuses primarily on the Khmer Rouge in power see Sok Udom Deth’s “The Rise and Fall of Democratic Kampuchea” Education About Asia 14, no. 3 (2009): 26-30. https://aas2.asian-studies.org/EAA/EAA-Archives/14/3/849.pdf.

[10] Friedrich A. Hayek The Road to Serfdom (Abridged). (Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation with permission of the University of Washington Press, 1972): 20.

[11] Michael T. Kaufman “Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who Defied Soviets, Dies at 89,” The New York Times, (Aug. 2008). https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/04/books/04solzhenitsyn.html?_r=2.

[12] Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I., In the First Circle, (New York: HarperCollins, 2009): 118.

Bibliography

China: A Century of Revolution. Directed by Lyman Will, Sue Williams, Kathryn, and Dun Tan Dietz. Performed by Ambrica Productions, WGBH (Television station: Boston, Mass.), Channel Four (Great Britain), WGBH Educational Foundation, and Zeitgeist Films. 1989-1997.

Constitutional Rights Foundation. “The Marshall Plan for Rebuilding Western Europe.” Bill of Rights in Action 20, no. 3. Summer 2004. https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-20-3-a-the-marshall-plan-for-rebuilding-western-europe.html (accessed 3 24, 2016).

Courtois Stephane, Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Panne, Andrzej Paczkowsi, Karel Bartosek, and Jean-Louis Margolin. The Black Book of Communism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Hosford David, Pamela Kachurin, and Thomas Lamont. Gulag: Soviet Prison Camps and Their Legacy. Cambridge: National Park Service, National Resource Center for Russian, East European and Central American Studies, Harvard, 2005.

Hayek, Friedrich A. The Road to Serfdom (Abridged). Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation with permission of the University of Washington Press, 1972.

Kenley, David. Modern Chinese History. Ann Arbor: the Association for Asian Studies, 2012.

Kaufman, Michael T. “Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who Defied Soviets, Dies at 89,” The New York Times, Aug. 4th 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/04/books/04solzhenitsyn.html?_r=2 (accessed March 24th, 2016).

McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1992.

My Cambodia. Directed by Morimoto Risa. Produced by Sekiguchi Rylan. Performed by Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. 2014.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. In the First Circle. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.