A nation must think before it acts.

Narva, Estonia, is a city of contrasts and constant concern. Estonia’s third-largest city, Narva is predominantly home to ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers, including many Russian citizens and stateless residents. The country’s rich oil shale region and part of Estonia’s former industrial heartland, Ida-Viru County, where Narva is located, has the country’s highest unemployment rate. Additionally, Narva often has diverged from nationwide politics or elections. For example, Narva held a failed autonomy referendum in 1993. It often votes differently than most other regions in parliamentary elections, including in 2019, in which Ida-Viru County’s electorate (including Narva) gave the Centre Party 35.4% of its vote.

Narva’s local differences have made the city a nexus for international media, policy, and research seeking to understand this borderland community and whether it constitutes a potential site of Russian state intervention or military conflict. At first glance, Narva mirrors the contentious contexts that led to Russian incursions in Georgia, Crimea, and eastern Ukraine. Such conflated parallels have led some experts to question Narva’s stability and secessionist potential, Estonian security and territorial integrity, and Estonia’s ability to include both Narva (and Ida-Viru County) and its large Russian-speaking population into the national fold.

While similarities are easily identifiable, these are conflations and generalizations that are not adequately reflected locally and on the ground, particularly among Russian-speakers themselves. Such differences have been illustrated in media and research, including that conducted by the author. Although this is the case, it is integral to assess continuously and understand this local area and its rooted Russian-speaking community, particularly as the Estonian state shifts more to the right, with anti-Russian-speaking community perspectives. Local voices and perspectives matter, particularly when a locality and its respective population are discussed in policy and planning, including those associated with national and regional security, stability, and militarization. Building upon previous research, this bulletin highlights recent findings from a 2018-2019 electronic survey among Russian-speakers who reside in Narva. The electronic survey was implemented with the assistance of local institutions and partners, including Narva College, Narva Municipal Library, and the City of Narva.

Sense of Place Survey

The survey partly builds upon previous research (author’s doctoral fieldwork) and emphasizes sense of place. Sense of place basically reflects people-place relationships and is illustrated through how or why people depend on, attach to, identify with, and attribute meaning to place, including countries, cities, or even neighborhoods. Sense of place is understood through and expressed via human emotions, memories, experiences, perceptions, imaginations, and actions.

For example, changes to a city or neighborhood, whether environmental, architectural, or social, may spark divergent attitudes or conflicts as some residents may prefer their place as-is, while others may prefer improvements or shifts. Sense of place can be a powerful tool that can assist researchers, planners, or policymakers interested in place-based problems. There are innumerable approaches to sense of place. For the purpose of this study, sense of place integrates: pride of place and local uniqueness; place meaning; place attachment; and place-based identity. Not all results are included in this brief; however, the findings illustrated provide enough to glean some key sense of place highlights.

Narva Residents’ Senses of Place

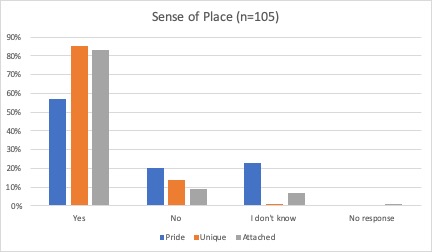

Survey respondents, consisting of current Narva residents (n=105), have a strong local sense of place. This strong local sense of place is reflected in survey responses associated with the aforementioned sense of place dimensions (e.g., place attachment, place identity, etc.) (see, Chart 1 and Chart 2). When asked to assess their level of pride in Narva, 57% of respondents stated that they are proud of their city. Such pride might be reflected in how respondents understand and engage locally, whether in civic, community, environmental, or political behaviors and activities aimed at building a stronger sense of local community. This strong sense of place is also reflected in responses to whether respondents consider Narva a unique place. Respondents overwhelmingly noted that they consider Narva unique (85%). When asked whether respondents are attached to Narva as a place, again respondents overwhelmingly stated they are attached with 84% providing a “yes” response.

Chart 1. Sense of Place Responses

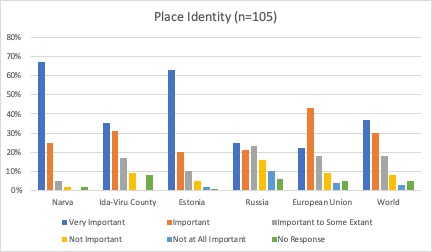

This strong sense of place also was reflected in the place identity question responses. Respondents were asked to assess the degree of importance for a range of places, including Narva, Ida-Viru County, Estonia, Russia, European Union (EU), and the world. By including all these potential responses, it provides a better understanding of the role that place(s) plays in how individuals or groups develop and exercise their various place-based identities that may shift over time. When it comes to these specific places, respondents noted that Narva (67%, very important) and Estonia (63%, very important) are the most important places of identification.

Chart 2. Place Identity Responses

While Russia and/or Russian-ness may inform Narva’s Russian-speakers’ identities (cultural, historical, linguistic, ethnic, etc.) and sense of community (local, regional, transboundary, etc.), Russia as a place identity is not considered as important in comparison to other locations (25%, very important and 21%, important). The findings also illustrate the potential emergence of an EU or shared European place identity, as the EU did resonate among respondents, including more than Russia (23%, very important and 43%, important). Such EU-relevant findings support recent EU membership polling among all Estonians more broadly. Other locations varied in their response patterns although it should be noted that other places seem more important to Narva’s Russian-speaking community than others.

Implications

Based on the survey findings and previous research, Narva’s residents have a strong sense of place. This strong sense of place is illustrated by their pride of place, place uniqueness, place attachment, and place identity. The findings also reflect the importance of Narva to local residents. Narva residents’ strong local sense of place is crucial to better understanding this important borderland city that is continuously under international media, policy, and research attention or scrutiny. If Narva residents maintain this strong sense of place, then how might they react to local, regional, national, or international policy or planning pressures or interventions?

This is particularly pertinent now as Estonia witnesses an increase in right-wing ethno-nationalist politics with the electoral successes of the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE) in 2019. The EKRE joined a coalition government in April 2019 along with conservative Isamaa (Fatherland) and centrist Centre Party, the latter of which long has been supported by Estonia’s Russian minority. The rise of the EKRE could be problematic for Narva as the party emphasizes an Estonia for Estonians ideal, maintains anti-Russian attitudes, has characterized Estonian Russians as a potential fifth column or untrustworthy, and is critical of Russian-language education. These values and interests are a reversal of relatively recent shifts towards greater inclusion of the area and community. If the EKRE’s policy platform and rhetoric impacts Narva’s population, then the consequences could be problematic. EKRE’s heightened anti-Russian and ethno-nationalist rhetoric feeds the potential of Russian influence or interventions, especially since the Russian state has accused Estonia of discrimination of what it considers its compatriots and has accused Estonia of glorifying Nazism.

Such impacts could complicate or hasten what NATO has called the “Narva scenario” or a potential Russian incursion into or annexation of this borderland city. For example, EKRE’s anti-Russian rhetoric or policy influences (e.g., citizenship or integration policy restrictions or shifts that may impact Narva’s Russian community negatively) could potentially reduce Narva residents’ fealty, trust, or strong sense of place towards Estonia or an Estonian Narva, which in turn could worsen historical social and political fractures. Such fractures may leave the door open to anti-Estonian (or anti-NATO) messaging, movements, or even Russian intervention.

While it is too early to assess EKRE’s impacts in the region or on Russian-speakers, EKRE does have considerable power as part of the governing coalition (splitting key cabinet positions), including through roles in the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications (Minister of Foreign Trade and IT), Ministry of the Interior (which coordinates the highly influential Police and Border Guard Board), Ministry of the Environment, and Ministry of Rural Affairs. Their influence already has been observed, including through pressures being placed on critical journalists along with widely publicized incidents with current President Kersti Kaljulaid and former President Toomas Hendrik Ilves. EKRE is not new to such controversies as illustrated by their rejection of former Foreign Minister Marina Kaljurand as a potential presidential candidate due to her Russian background in 2016, noted use of the far-right hand gestures during swearing-in ceremonies in 2019, and recent anti-LGBT clash. Additionally, some media commentators have noted that the Centre Party’s decision to form a coalition with the EKRE may be negatively impacting its Russian minority electoral base.

The preliminary survey findings reflect a strong-rooted, place-based community with a high sense of attachment and identity that is bound to both Narva and Estonia with slight variations. This strong sense of place potentially illustrates how Narva’s residents may react to such pressures of interventions. Narva’s residents may be resilient to external or internal threats, depending on the motivations, impacts, or other factors. However, such strong senses of place and resilience may also inform strong responses to such threats, such as anti-Russian or anti-Estonian movement mobilization, as seen in Tallinn in 2007 or Narva in 1993, particularly if interventions alter what makes Narva unique and home to this local community.