A nation must think before it acts.

Executive Summary

Russia’s policy execution structure decentralizes responsibility for the reintegration of war participants, while centralizing credits for success stories, because the execution of the policy is rife with political risks but keeping the narrative of reintegration under tight control is a vital objective for the Kremlin. Decision-makers up to the president view the eventual return of hundreds of thousands of war participants as a potential domestic destabilization risk due to fears of boosting violent crime, organized crime, alcoholism, and drug use, similar to patterns observed with Afghanistan veterans. Political responsibility for managing and executing contentious and costly reintegration policies is decentralized to regional and local governments and major employers. This approach places the political risk and financial burden, through mechanisms like hiring quotas and various allowances, onto regions that often lack the necessary resources and political maneuvering space, risking highly varied standards of support across the country. The specifics of Russian post-war economic recovery, which partially depend on sanctions relief, will be a determining factor as regards the difficulties associated with reintegration.

The Russian state has the financial resources to finance rehabilitation and reintegration, but lacks the necessary social infrastructure capacity, particularly in healthcare and law enforcement. Despite the federal establishment of bodies like the Fund for the Defenders of the Fatherland (FZO) to oversee assistance and act as a one-stop shop, actual service delivery is reported to be slow and lacking. The healthcare system faces significant capacity shortages, with full standardization of treatment planned only by 2030. Simultaneously, law enforcement capacity is severely depleted, with a nationwide shortage of more than 170,000 Interior Ministry personnel, making it questionable whether the state will be able to contain the predicted rise in violent crime. These are the results of several years of underinvestment in social infrastructure, which regions are not incentivized to do.

The Kremlin’s efforts to establish a “new elite” are primarily political branding and the majority of veterans are unlikely to benefit from advancement opportunities. President Vladimir Putin has underlined war participants’ elite status by providing symbolic benefits and establishing political pipelines like the “Time of Heroes” program. While these may have helped to maximize the recruitment effort, the narrow nature of elite programs means most opportunities are reserved for career soldiers or pre-existing officials. This divergence between official heroic rhetoric and the reality of limited opportunities, coupled with public attitudes regarding soldiers’ motivations and concerns over increased crime, risks generating future frustration among the returning population. At the same time, returnees have not yet coalesced into a political class or unified pressure group due to their diverse backgrounds and lack of cohesive, independent structures, and the Kremlin is interested in keeping it this way.

Introduction

Efforts to bring Russia’s war against Ukraine to a conclusion or a stable ceasefire have so far failed, in part due to a failure among diplomatic decision-makers to understand the motivations of the Kremlin, which has so far starkly rejected any peace process that risked even minimally diverging from its own terms. Nonetheless, given the growing pressure on the Russian economy and the federal budget, this may change in 2026. It is plausible that in the not-too-distant future, in the event of a ceasefire or peace deal, Russian soldiers now serving in Ukraine are going to return to Russia without having reached Russia’s initial war aims.

In September 2025 a Reuters report suggested, based on Kremlin-adjacent sources, that decision-makers up to the president saw the eventual return of hundreds of thousands of war participants from Ukraine as a potential destabilization risk due to fears of these men providing a boost to opportunistic, violent and organized crime, similarly to what happened with the veterans of the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan.[1] Russian independent media have also reported similar fears, including of the effects of rising alcoholism and drug use.[2] A June 2025 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, authored by Mark Galeotti, focused mostly on the criminogenic effects of the reintegration challenge, highlighting similar patterns but also differences between the two periods.[3]

At the same time, since at least February 2024, President Vladimir Putin has been arguing in favor of turning war participants into a “new elite”. Through mostly the governing United Russia party and direct appointments, war participants—including former officials who completed a stint as a member of specialized battalions in Ukraine—have been placed in various legislative and executive positions. The federal government has also underlined war participants’ elite status by providing them with various symbolic benefits, ranging from “Hero of Russia” decorations to free or subsidized transportation, land ownership, and public speaking opportunities, among many others. This already highlights gaps between official rhetoric and expected risks, but the system has not faced its real test yet.

This report argues that part of the reason the eventual return of war participants does pose a risk to domestic stability is the structure of Russia’s policy execution that devolves political responsibility for managing and executing contentious policies to lower levels, without providing the necessary resources and political maneuvering space. This makes the Russian state and its social infrastructure ill-equipped to deal with the pressure of reintegrating war participants into Russian society.

It also argues that while the “new elite” of war participants has been successfully turned into a political brand over the past two years, war participants, drawn from diverse backgrounds and as a consequence facing very different palettes of opportunities, have not yet turned into a political class or pressure group. This, instead of the Kremlin’s consciously trying to create closely supervised channels for returning war participants to express themselves, may change in the future as the limits of state capacity to care for veterans become visible and existing differences over domestic policy make it attractive for domestic players to harness the brand that the Kremlin has helped to build.

Domestic Policy Problems

The number of Russians currently present in the zone of warfare has varied over time and has been subject to speculative guesses. In September 2025, Putin said that 700,000 soldiers were present in the “special military operation” zone in Ukraine.[4] Three months earlier Putin’s office claimed that some 137,000 soldiers had already returned from the war.[5] Between 145,000 and 219,000 soldiers have been killed as of November 2025, according to the count and estimate of BBC and Mediazona based on publicly available data.[6] The number of wounded soldiers is also in the hundreds of thousands.

This includes mobilized and contract soldiers, volunteers, and private military company personnel. Focusing in on mobilized soldiers of the Siberian region of Tomsk, a September 2025 investigative report by the iStories media outlet found that 11.6 percent of mobilized men from the region had verifiably died, a further 12.6 percent were injured and 5.2 percent had gone missing or deserted.[7] While one region is not necessarily representative—Tomsk was in the lower middle range of verified losses to population ratio in the BBC/Mediazona study—it provides a sense of proportion for the issues the state will face in connection with military losses and demobilization.

An uptick in violent crime is of particular concern already. Media reports have described a severe increase in violent crime and looting in Russia’s regions bordering Ukraine.[8] In a more scattered manner, returning soldiers with a criminal record have also contributed to a well-documented wave of violent crime across the country.[9] According to a count by the news outlet Vërstka, based on court records, 754 people fell victim to violent crimes committed by returnees in the first three years of full-scale warfare; the vast majority of these crimes were committed by former felons who took the opportunity to fight in Ukraine as a way to get out of prison.[10] This could get worse with the return of more soldiers from the front. It was estimated by Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service that, as of early 2025, at least 180,000 of the total headcount of Russian soldiers who have fought in Ukraine are convicted felons released from Russian prisons.[11] While this number cannot be verified, official Russian statistics on prison population decline have suggested similar, if slightly lower, figures: According to official data from the Federal Penitentiary Service, the prison population declined by 120,000 between January 2023 and January 2025.[12]

However, soldiers recruited from civilian professions, who are more numerous, are also a cause for concern. Narcotic use is a widely documented phenomenon among Russian troops in Ukraine, as is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can cause unpredictable, asocial, or violent behaviors.[13] This can hinder reintegration and even change society’s picture of the returning soldier, with citizens eventually more actively questioning the Kremlin’s narrative of the new elite.[14] Even Villi Maslov, a researcher of the Russian Interior Ministry’s Ural Law Institute, warned of a coming violent crime wave in Russia following the war, due to recidivism as well as post-traumatic stress, even in soldiers without existing criminal histories.[15]

Decentralized Risks and Responsibility

Based on the experiences of crisis management during the 2020–21 COVID crisis and the aftermath of the failure of the initial “special military operation” plans in 2022, when regional governments were tasked to implement and fine-tune policies such as lockdowns, vaccinations, and military recruitment based on guidelines and signals provided by the federal government, it seems likely that the federal government will again task regional governments and—often through them—major employers to serve as an extension of the federal state and assume the costs and, in the case of local and regional leaders, the political risks associated with the reintegration of war participants. As will be pointed out below, in several regions the authorities handpick war participants to act as a buffer between themselves and their peers, by appointing them to unelected positions created to oversee veterans’ affairs.

A regional resource center for war participants opened in 2023. (Press Service of the Head and Government of the Udmurt Republic)

While political responsibility is decentralized, similarly to earlier crisis situations, there is already indication that federal structures will attempt to take credit for success stories. The Kremlin set up the “Fund for the Defenders of the Fatherland” (FZO) in 2023 as an umbrella organization to oversee assistance to returning war participants.[16] It is led by deputy defense minister Anna Tsivilyova, one of Putin’s cousins. The FZO has divisions in Russia’s regions as well as in the occupied territories of Ukraine, and was planning to employ up to 11,000 social coordinators to assist returning war participants with getting medical and administrative help (as of 2025 it employed around 4,000). In the State Council, an important consultative body that acts as a forum for regional leaders and the Kremlin, Igor Babushkin, the head of the Astrakhan Region, a former FSB and military officer, is supervising policies related to veterans.[17]

The appointment of a trusted associate of Putin and a governor with an FSB background to spearhead the federal effort to reintegrate war participants also hints at the Kremlin’s other main objective: to keep the social and political organization of war participants, no doubt considered a sensitive and risky issue, under the tightest possible control.

It is important to note that while, based on its communiques, the FZO has procured and provided a small amount of goods and services such as prosthetic legs and refurbishment of veterans’ apartments, it does not itself provide all the help it claims to offer.[18] Often it simply provides assistance and a one-stop shop, similar to a smartphone app launched in July 2025 in the Arkhangelsk Region.[19] Actual service delivery has reportedly been slow and lacking.[20] Its initial grant of 1.3 billion rubles overwhelmingly financed overhead costs (818 million on salaries, more than 200 million on office space), with only a small fraction allocated to the provision of services.[21] In 2023–24, according to the estimates of Agentstvo Media, at least 25 percent of the total grant allocated to the fund was spent on payroll and a copious amount of funding on self-promotion, even as spending on goods and services remained low enough that in 2024 the government cut the amount of funding initially allocated to the FZO. In 2025, however, the budget has grown significantly, from an initially planned 13.7 billion rubles, first to 25 billion and then to 35 billion, but it is yet unclear where this additional money was spent.[22]

The actual impact of the FZO on easing the problems of returning war participants is difficult to assess, even after more than two years of the organization’s functioning. However, it fulfills a more important function: by acting as a one-stop shop and keeping in close contact with regional administrations, it can exercise control over regional policies and the communication of success stories.

Support Programs

Apart from sign-up bonuses and salaries, war participants and their families are entitled to receive a range of further payouts from the federal and regional governments. The government pays 3 million rubles for grave injuries (4 million if the injury leads to permanent handicapped status) and one million for light injuries, along with (meager) veteran pensions. Monthly social payments of 158,000 rubles are provided to mobilized soldiers.[23] Regions supplement these payments from their own budgets, but payments vary considerably between poorer and wealthier regions and can be subject to delays and administrative holdups.[24] Veterans also benefit from a range of smaller federally mandated allowances, such as free public transportation, a write-off of housing and utility costs, free meals for soldiers’ children, or loan payment deferrals and write-offs, most of which also come out of regional and local budgets and the balance sheets of banks.[25]

The federal government provides multiple tax exemptions, primarily covering personal income and property taxation, as well as several state fees. War participants are not affected by higher personal income tax rates adopted in 2024 and they enjoy tax exemptions on a range of payments to both themselves and their families in connection with their service, injury, or death. Soldiers and their families are also exempt from paying various fees. [26]

War participants are also exempt from paying land tax on property for one object of each kind of real estate (e.g., one house, one apartment, one garage) and eligible for tax breaks on land tax for land plots. They are also exempt from paying transport taxes for automobiles with an engine of up to 150 horsepower.[27] All of these impact regional budgets. Regional budgets also provide grants to returnees under various programs such as the “Agromotivator” program, which aims to help veterans start their own agribusinesses and can theoretically allocate funds of up to 5–7 million rubles in 19 regions.[28] These grants are subsidized by the federal budget; however, under tight budgetary conditions they can crowd out subsidies for other purposes.

Attendees at a December 2025 forum in Moscow focused on resources for veterans. (Защитники Отечества/Defenders of the Fatherland/VK)

The federal government has also encouraged regional governments to go beyond federally mandated measures and many do, partly in an attempt to signal loyalty to the Kremlin and to enhance their chances of obtaining more funds for the accomplishment of policy goals.[29]

The Lipetsk Region, the Arkhangelsk Region, the Tyumen Region, Karelia, and the Perm Territory, for example, extended the group of those exempt from paying transport tax.[30] Some regions also went further on housing subsidies. The Far Eastern region of Sakhalin provides a lump-sum support for veterans’ initial mortgage payments. Similar payments have been set up in the Perm Territory and North Ossetia.[31] The Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Region, like Sakhalin a hydrocarbon-producing region, gives war participants priority when distributing social aid for housing.

Several regions have announced granting land plots to returning war participants to build on.[33] In some, such as the Moscow Region or the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District, instead of a land grant veterans can apply for a lump sum payment.[34] Many, typically poorer, regions provide social support such as lump-sum subsidies between roughly 10,000 and 25,000 rubles for the families of war participants to buy solid fuel.[35] Similar schemes provide school meals for soldiers’ children, stipends at the beginning of school years or other payouts at the birth of children in veterans’ families.[36] These are relatively inexpensive measures in regional budgets, which however allow governors to signal loyalty to the federal center by combining various priority policy goals (e.g., raising fertility rates and looking after returning soldiers).

Other regions are focusing on business support as a means of lessening the burden of finding employment for returning soldiers (see below). The Stavropol Territory announced preferential microloans and credit holidays for veterans and their families who run businesses serving the army or social sector.[37] The Orenburg and Kemerovo Regions have recently announced subsidized loans for veterans starting businesses. Such programs are going ahead in spite of problems with regional finances that can hinder their provision. In 2025 the Belgorod Region set up a competition allowing war participants to launch their own entrepreneurial projects with support from the regional budget, even though as of late 2025 the region was struggling to meet its regular budgetary expenditures.[39]

Employment Challenges

In June 2025 deputy prime minister Tatyana Golikova claimed that 57 percent of returnees had found employment, the vast majority (80 percent) of them with a formal employment contract and the rest in self-employed positions. It is worth noting that officially, war participants who held jobs prior to being called up or signing up to serve in the army enjoy a guarantee to return to their old place of employment within three months of completing their service.[40]

From August 2025 on a growing number of regions started introducing quotas for hiring returning war participants that employers need to observe, in addition to federally established quotas for employers to hire handicapped workers. Some regions (e.g., Vologda) are or are planning to fine employers that do not.[41] As of November 2025, the program, a federal pilot that started in the Moscow Region—as federally mandated regional policies that are rolled out gradually often do—has been taken up by a handful of regions in Central Russia and the Urals. In some regions the quotas concern employers with over 100 employees; in others, the numbers are lower.[42] The Penza Region authorities, for instance, mandate employers with teams between 36 and 100 people to employ one returning war participant, and larger companies to keep one percent of their positions open for war participants.[43] Initial feedback suggests that demand has so far been low, with only about 300 people applying for positions in the Moscow Region in the first four months of its program.[44] However, with the return of the bulk of war participants these numbers will almost certainly grow. Simultaneously, quotas could too, although there is no guarantee that the jobs created this way will be well-remunerated or adapted to veterans’ skillsets.

The compensation of employers for the losses suffered due to obligations to employ and retrain war participants varies. There are several examples of regional governments compensating employers: In the Sverdlovsk Region, governor Denis Pasler announced in October 2025 that the regional budget would reimburse 50,000 rubles per month per person for the duration of six months after each returnee employed by the region’s organizations and enterprises.[45] Other regions pay compensation after the first, third, and sixth month of employment based on the minimum wage and a regional coefficient.[46] Yet in its current state, the program is a classic example of the federal government outsourcing political responsibility for an important but contentious policy to regions, which, depending on their budgetary capacity, then partially outsource costs to employers.

A more direct way of solving the problem with jobs is creating positions in public administration and institutions funded by the state. This has been the purpose of the “Time of Heroes” program, first launched at the federal level in 2024 and then gradually in regions. But this represents a very limited pipeline.

First Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, Police Colonel General Alexander Gorovoy, took part in commemorative ceremonies honoring fallen law enforcement officers during a November 2025 working visit to the Donetsk region. (Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation/VK)

Of more than 65,000 applicants in the federal “Time of Heroes” program, as of late 2025 only 168 have been admitted.[47] The overwhelming majority of these applicants are not mobilized servicemen or contract soldiers, but career soldiers or former public officials. The Novaya Gazeta newspaper identified only three mobilized men in the first year of the program.[48] 83 applicants graduated in 2024 with a second track started in 2025, but as of October 2025, only about 60 were appointed to various federal and regional positions according to the Kremlin’s own numbers.[49] Urals presidential plenipotentiary Artyom Zhoga and Tambov governor Yevgeny Pervyshov were appointed to top-tier positions that come with a degree of political clout. Many others have served in positions overseeing youth policy and policies affecting returning war veterans.[50] Those who hold other positions had typically been part of the administrative elite before their service in the war. For example, Georgy Andreev, the minister for enterprise, trade and tourism of the Sakha Republic, had been deputy minister prior to going to the war; Pervyshov himself had been a Duma deputy and mayor of Krasnodar.[51] This tendency is observable even at lower levels of public administration.[52] This puts a significant dividing line between the opportunities this already very limited program presents to returning war participants.

In May 2025 the Kremlin set key performance indicators related to the employment of returnees to regional governments. These oblige regions to find employment for 30–60 veterans a year in state-sponsored positions through regional equivalents of the “Time of Heroes” program.[53] But even these regional equivalents represent a very narrow avenue to jobs. Regional programs have typically selected one in 15 (the federal program one in 400) applicants. The federal government earmarked 562 million rubles for the education of returnees through these programs in 2025, but this only covers some 5,000 war participants, less than 4 percent of those who have returned from the war so far.[54]

In the same vein, some have voiced plans to fill the ranks of law enforcement with returning soldiers, and this idea has been supported by the Kremlin in principle.[55] Indeed, as outlined below, as of early 2025 the Interior Ministry faced a shortage of more than 170,000 employees, a much larger number than can be employed through the “Time of Heroes” program in its current form. However, due to the high expected number of traumatized, injured, criminal, and narcotics-addicted soldiers, the overall feasibility of this plan is questionable.

For the amount and type of state support needed to reintegrate war participants, the type of economy that soldiers return to will matter a lot.

The full-scale war has exacerbated Russia’s pre-existing labor shortage problem by removing hundreds of thousands of able-bodied men from the job market, prioritizing defense-industrial sectors to the detriment of the civilian economy, and—indirectly—by spurring ultraconservative policies such as a tightening of regulations on migrant workers. As of November 2025, the labor market remains tight, but cadre shortages have begun to ease. The growth of real incomes has slowed down in 2025, to 3.8 percent year-on-year as of August.[56] The growth of personal income tax receipts in regions, which did not benefit from tax hikes, have also shown a slowdown in 2025, suggesting an easing of the wage war that had characterized the domestic economy in the three years of the war so far.[57] All this is happening while the fiscal space of potential employers is shrinking. Corporate income tax receipts recorded in regional budgets started falling behind expectations in late 2024 with the negative trend continuing in 2025.[58] Both Russia’s own statistics on industrial production and indicators such as S&P’s Purchasing Manager Index have shown a slowdown and expected downturn in key manufacturing sectors in the second half of 2025.[59] The Russian Central Bank itself noted in September 2025 that tight labor market conditions were easing in several regions.[60]

In order to ease the burden on social budgets and employers for the time being, the federal government may also opt for gradual demobilization, releasing only a small number of job seekers onto the job market at a time. This would essentially shift the financial burden of reintegrating war participants to the federal budget and away from regions and enterprises.

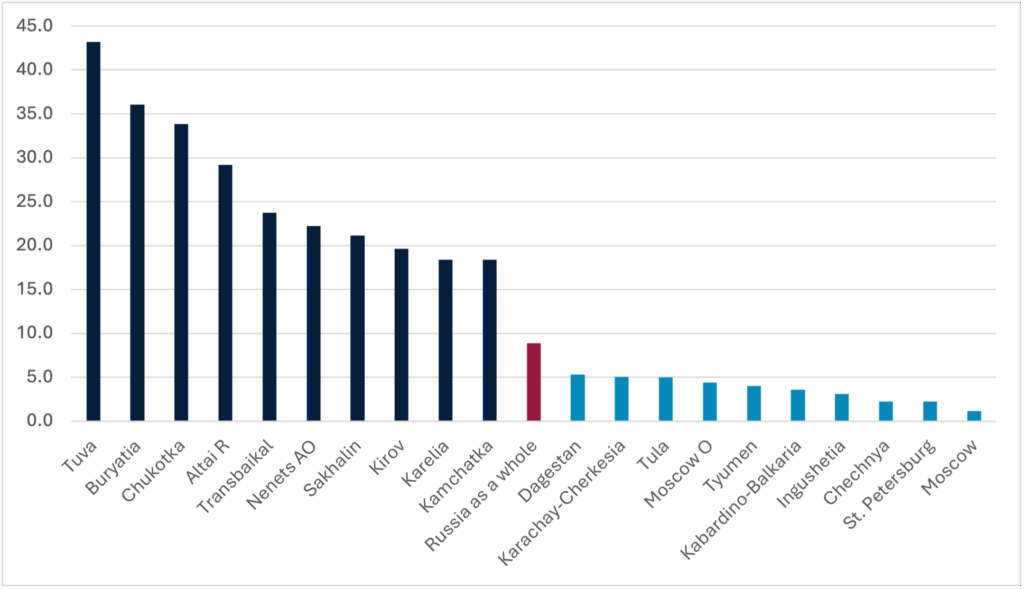

Figure 1. Verified battlefield losses by 10,000 citizens, top 10 and bottom regions only, October 2025

Source: Rosstat Population Statistics, https://rosstat.gov.ru/free_doc/new_site/popuation/demo/dem11_m p.htm, accessed November 9, 2025; “Poteri Rossii voĭne s Ukrainoĭ” [Russia’s losses in the war in Ukraine], Mediazona, updated November 7, 2025, https://zona.media/casualties. Author’s own calculations.

What growth opportunities civilian sectors will have access to in the event of a ceasefire or peace talks and in which regions will greatly depend on the pace and the type of sanctions relief, over which the Russian government has only limited control. This matters because demobilized war participants may not be located in regions where labor demand is growing and may face mobility challenges, increasing costs for employers, the authorities, or both. Verifiable casualty figures compiled by BBC and Mediazona show large discrepancies between the human toll of the war on various regions (see Figure 1), with some poorer Far Eastern and Siberian regions (e.g., Tuva, Buryatia, or the Transbaikal Territory) experiencing a verifiable loss of 20–40 people per 10,000 residents, with wealthier and more industrialized regions (e.g., Moscow, St. Petersburg, or Tyumen) only 1–4 per 10,000 (although actual numbers are likely higher in both cases).[61] The influx of money into regions with a higher number of contract and mobilized soldiers and casualties has arguably led to a boost in consumption, but this alone is unlikely to sustain a post-war economy. The defense-industrial complex has been the other, bigger driver of economic growth, and spending on the state defense order is expected to remain high even after the end of active warfare as the Russian military is rebuilt.[62] However, 2025 has so far seen an easing of the wage race even in these sectors as military production hit productivity limits.[63]

It is important to note that employers will, in some cases, compete not only with each other but also with “hiring” in the illicit sector. The risk of this will remain high especially if the conflicts over the redistribution of assets triggered by the wartime restructuring of the Russian economy remain and if the federal and regional governments are seen as unable to establish and enforce clear rules to govern these conflicts. This situation would be not unlike the business atmosphere of the early 1990s, which helped illegal and semilegal businesses absorb veterans returning from the war in Afghanistan as hired muscle.[64]

Public Services

As laid out above, two of the most pressing problems associated with the return of Russian soldiers from Ukraine concern mental and physical health (including addiction) and the partially overlapping problem of a rise in criminality.

According to the Russian government’s own estimate—voiced by Tsivilyova, who oversees affairs related to returning war participants—around 20 percent of returning war participants will experience PTSD. The V. M. Bekhterev Center for Psychiatry and Neurology put this proportion between 3 and 11 percent, allowing that among those who suffered an injury it could be as high as 30 percent. These are conservative estimates, with experts suggesting that the real proportion may be even higher, especially considering that family members of returning soldiers can also fall into this category.[66] Already in 2023 Russian experts estimated the number of returning war participants needing some sort of psychological help at 150,000.[67] Based on the above estimates, the actual number could very well be over 200,000.

An analysis by Thomas Lattanzio and Harry Francisco Stevens in 2024 estimated the costs of treatment in Russia at $15,000 per soldier per year, a staggering amount given the large number of soldiers who will presumably need it.[68] This estimate, however, was based on the approximate cost of such treatments in the United States—a country with notoriously inflated healthcare costs—adjusted for purchasing power parity, and not on Russian treatment standards and prices. The standards of the Russian Ministry of Health prescribe at least 15 sessions for returning war participants. Treatment needs vary, but altogether the ministry estimated in 2023 that the average length of PTSD therapy for returning soldiers who need it is 325 days.[70] Assuming that the costs of therapy for soldiers are comparable between Russia and Ukraine, where weekly costs were given as $150 in 2023, this would assume a yearly cost of around $1 billion or 80–81 billion rubles at current exchange rates.[71]

Penza police officers returned home after a six-month deployment to the North Caucasus. (Ministry of Internal Affairs/VK)

This is already a significant amount of money, equivalent to the yearly budget of poorer mid-sized regions, but this estimate assumes that every person who needs PTSD therapy is able and willing to get it. This is far from certain. Sectoral experts have pointed to stigmas associated with psychological therapy as well as the unavailability of psychiatric practitioners.[72] This makes the claims of health minister Mikhail Murashko that “100 percent” of returnees who needed psychological help received it questionable.[73] The longer-term effects of untreated psychological problems will also weigh on the state’s finances, and may represent a larger burden than the upfront costs of treatment would, but these costs will be spread out unevenly over time and across budgets.

In February 2025 the Ministry of Health issued guidelines uniformizing the standards of providing health and social rehabilitation measures across regions, based on a 2023 law that defined the elements of “comprehensive rehabilitation.”[74] However, the ministry itself recognizes that due to the significant differences between the quality and the capacity of healthcare and social services between regions, a simple switch to these new standards is not possible; their adoption is planned over almost five years, by 2030. Places are scarce, too. Since 2025, returning war participants have been able to get placed in one of the twelve rehabilitation centers run by the Social Fund of Russia (SFR).[75] These therapies, however, are short-term and take 21 days once a year, depending on the availability of places, and, as researcher Dara Massicot pointed out in 2023, the institutions are often unable to provide the quality of care needed.[76] In 2025 the SFR was planning to provide these short-term therapies to a mere 17,000 war participants, albeit the government plans to build 10 more specialized institutions. In another scheme, the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District, a wealthy oil-producing region, is offering rehabilitation certificates to soldiers and their families.[77]

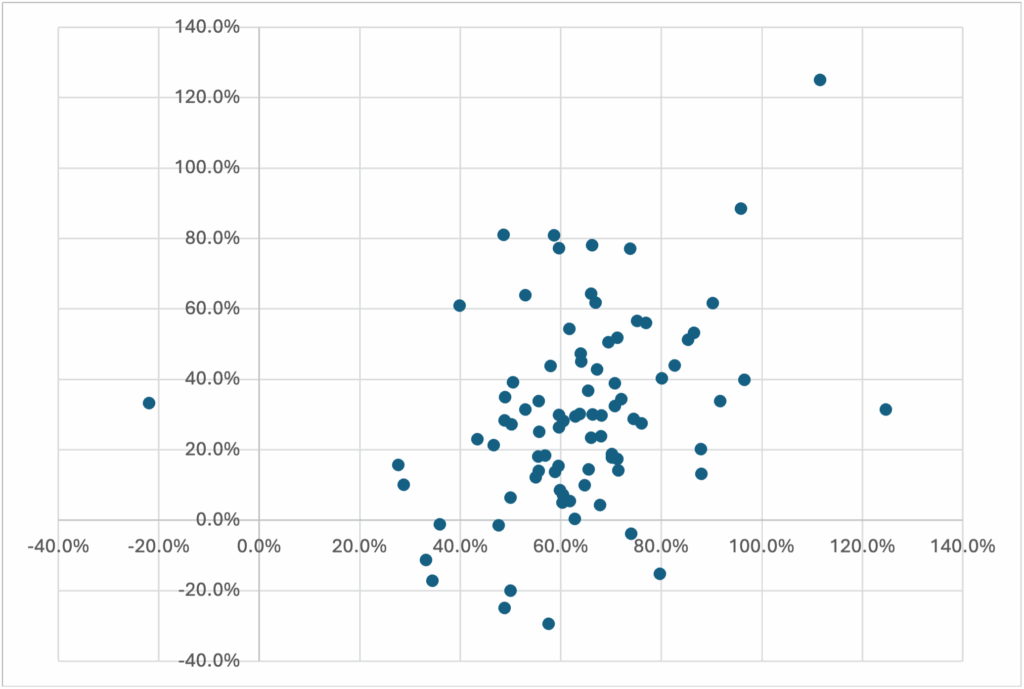

Figure 2. Cumulative growth of personal income tax receipts (2022-September 2025) and healthcare expenditures (2023-September 2025) in regional budgets, percent

Electronic Budget, https://budget.gov.ru, accessed November 9, 2025.

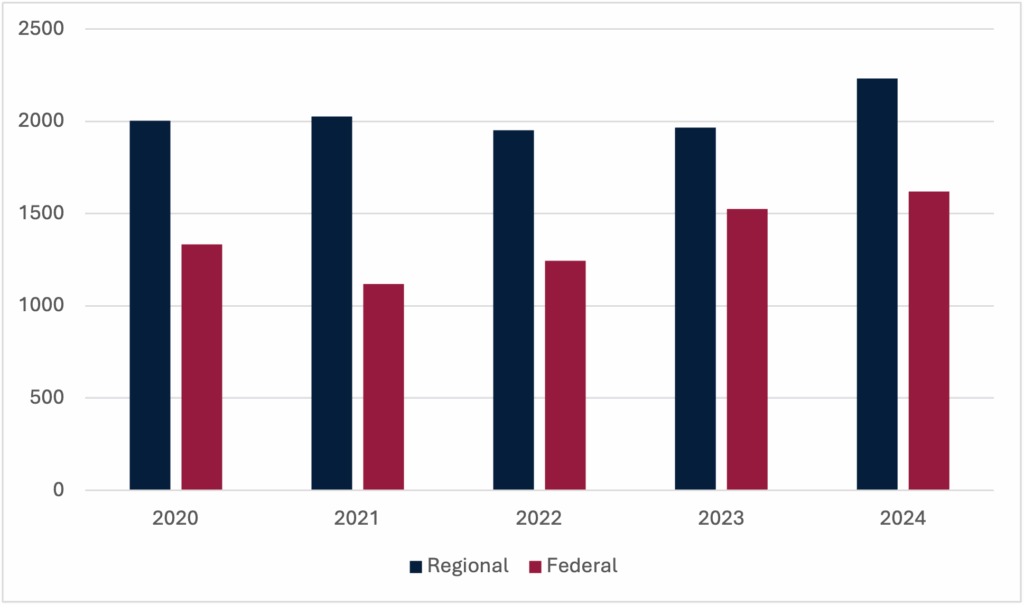

Figure 3. Federal and regional spending on healthcare, 2020-24, billion rubles

“Operativniĭ Doklad o Khode Ispolneniya Konsolidirovannykh Byudzhetov Sub’yektov Rossiĭskoĭ Federatsii, yanvar’- dekabr’ 2024 goda” [Operative Report on the Implementation of Consolidated Budgets of the Subjects of the Russian Federation, January December 2024], Audit Chamber of the Russian Federation, 2025, https://ach.gov.ru/upload/iblock/1da/jvb8h6wl8r2ycmnepry019p0mlssa6q7.pdf; Electronic Budget, https://budget.gov.ru, accessed November 9, 2025.

One of the main problems is a lack of capacity not only in specialized hospitals but in the Russian healthcare system in general. In case of increasing pressure on the system, this could mean that either returning soldiers or civilians will find it more difficult to obtain care. According to an October 2025 survey by the SuperJob website, medical organizations faced the largest labor shortages in the country, with 90 percent of those surveyed reporting difficulties with hiring, mostly general practitioners and nurses.[78] The situation is especially bad in poorer regions without large population centers, as recent years have seen wealthier regions drawing medical personnel from poorer regions, often with targeted campaigns. According to the government’s own estimates, in 2025 there was a shortage of 23,300 doctors and 63,500 mid-level medical personnel.[79] As of November 2025, the federal government is trying to improve the situation with a bill introducing mandatory work experience for medical school graduates in state hospitals. The “systemic” opposition party New People proposed a state-funded training program for therapists able to treat PTSD.[80] But once again, even government projections do not expect these measures to mitigate the problem before 2030.[81] As a stopgap measure, as of 2025, several regions have started raising bonuses for medical personnel from their own limited funds.[82]

Regional budgets are already responsible for a substantial part of healthcare expenditures, including the maintenance and construction of regional hospitals and the payment of medical workers. Federal spending on healthcare made up around 40 percent in the past three years with the rest accounted for in regional budgets (see Figure 3), albeit a substantial part of regional spending is supported by budgetary grants and targeted subsidies from the federal center. The task of paying for the upgrading and expansion of regional hospital networks and retaining medical personnel would fall on regional budgets.

The COVID-19 crisis led to a short spike in healthcare expenditures in regional budgets across the board, but this was followed by a decline, in 2022–23, of 4 and 5 percent in nominal terms, respectively.[83] In 2024 spending grew again, by 16 percent, and by 2 percent in 2025 (taking planned spending figures for the latter year), but this was not enough to offset inflation in 2021–25. And even this spending hike has been driven by only a small number of regions, highlighting a growing discrepancy between the means of wealthier and poorer regions to hire and retain medical personnel: Only 20 regions have raised their healthcare expenditures by over 50 percent in nominal terms since the full-scale war began (in 2023–25 budgets). A 2025 report by To Be Exact, a data analysis project, found large discrepancies in healthcare accessibility between poorer and wealthier regions, with an increasing number of doctors choosing to work at private clinics.[84] Psychiatrists were one of the least accessible kinds of specialists, with fewer than 0.8 practitioners per 10,000 citizens in some poorer regions.

The situation is even worse in the field of Interior Ministry personnel. In March 2025 interior minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev said that overall there was a shortage of 172,000 personnel countrywide, up from 90,000 in November 2022. In certain regions, such as the Maritime Territory or the Ivanovo Region, almost a third of vacancies remained unfilled.[85] In more than a third of the ministry’s regional organizations the shortage was over 20 percent. Another study by To Be Exact, focusing specifically on district police officers, came to a similar conclusion, highlighting that, on average, the shortage of this kind of police personnel was 36 percent across the country, with 14 regions facing extreme shortages.[86]

This is, to a significant extent, itself the consequence of the war in Ukraine: The police have been unable to compete with the hiring power of the army and the defense-industrial complex.[87] Regional and local budgets have themselves exacerbated the flight of suitable candidates from the service as they have been compelled to offer high sign-up bonuses for contract soldiers, limiting their ability to raise salary support for law enforcement and consequently making it more difficult to face an upcoming crime wave. Increasing regional bonuses to retain and increase police personnel has had some positive results on the number of personnel, but most regions lack the funds to increase these bonuses substantially.[88] In October 2025 the State Duma responded to police personnel shortages by lowering hiring standards.[89] Another bill, introduced by the nominally opposition Liberal Democratic Party, suggested offering police officers nearing retirement age substantial bonus payments to deter them from retiring from the force.[90]

Causes of the Lack of Capacity

The main problem with expecting regional governments to focus on maintaining and upgrading key social infrastructure is with incentives. During the full-scale war, regional budgets have become increasingly dependent on revenue sources that they cannot control or influence: The main driver of regional revenue growth has become personal income tax receipts, which are mostly the consequence of the federal government’s increased spending on war-related goals (making these gains a sort of income transfer) and various kinds of federal budgetary loans. At the same time, federal budgetary grants that regions can use at will have been cut since 2023, and corporate income tax receipts, one of the two main sources of regions’ so-called own income, started declining in the second half of 2024 (and are likely to remain depressed for the foreseeable future).[91]

For the sake of domestic political stability, regions are also being asked to prioritize goals such as keeping local economies alive and supporting social policies related to the war. In the first half of 2025, regional spending on the economy (24.1 percent) and social policies (22.4 percent) grew much faster than any other spending category.[92] A substantial part of the social spending growth itself has to do with the war: according to estimates published in Novaya Gazeta, in 2024 regions outside of Moscow spent more than 800 billion rubles—or at least 4 percent of their total budgets on average—on war-related goals (e.g., social aid, civilian defense, or recruitment bonuses), almost twice as much as they had originally planned, not even accounting for “hidden” spending (e.g., to support construction projects in the occupied territories) that would likely push this percentage even higher.[93]

This is in line with the self-reported expenditures of some regions. In 2024 the Nizhny Novgorod Region spent 24 billion rubles on “the support of the special military operation,” according to the head of a fund supporting the Russian army, who spoke in the presence of the region’s deputy governor.[94] This is 6.2 percent of the region’s total expenditures in that year. In 2026 the Leningrad Region will spend 13.3 billion rubles on the support of war participants and their families.[95] This is 3.7 percent of planned regional expenditures, but it is just a part of war-related expenditures, and often subject to upwards revision during the year.[96]

While regions will be able to cut certain expenditures in the case of a ceasefire (e.g., recruitment bonuses and payments to recruiters), these make up only 5.4 percent of identifiable war-related expenditures, based on the Novaya Gazeta investigation, and even after adding all defense-related expenditures, the figure only grows to 37.4 percent.[97] For reasons outlined above, social spending is expected to remain high even in the event of soldiers returning from the front, representing a constant elevated burden on regional finances.

Beyond this, regional governments are incentivized, including via the system of key performance indicators, to prioritize spending on goals that they either have very little control over (e.g., improving fertility figures) or whose only purpose is to signal loyalty (e.g., “fostering patriotic education”).[98] Given the growing dependence of regional budgets on federal sources, this is especially salient.

Under such conditions of increasing pressure and falling incomes, regional governments are incentivized to limit expenditures on policy goals that are not currently in the focus of federal supervisors, that do not represent an immediate political risk, and where they can reasonably hope that in case of a major crisis federal subsidies would be raised. A recent example concerns spending on housing and utilities. This grew by a little over 9 percent in the first half of 2025—that is, barely above inflation—even though the worsening state of public utility networks made this issue a priority.[99] Regions, however, seem to be putting these investments off in anticipation of their turn in the federal government’s debt forgiveness program.

The range and type of support measures beyond federally mandated standards ultimately depends on the fiscal capacity of regions, but regional governments are encouraged to prioritize these policies even when the funding is uncertain. So far, the extra burden on regional budgets has remained relatively small, but as the war continues, this number will grow, and the return of war participants will likely result in heightened demand for certain types of support (like housing aid or subsidized loans) and for healthcare and law enforcement capacity, which, even if regions receive further allotments from the federal budget, are difficult to quickly expand.

The actual provision of various payments can also suffer delays due to administrative reasons or excessive burden of proof on beneficiaries, regardless of federal financial support, especially when demand is high, as highly criticized delays with the provision of housing aid in the Kursk Region showed in 2024–25.[100] However, withdrawing already introduced aid programs is politically risky, therefore growing demand may lead to growing differences between the standards of social aid in richer and poorer regions, as well as frustrations resulting from the provision of payments.

Political Emancipation

The Kremlin’s master narrative for war participants has been one of heroism and the emergence of a new elite. Over the past years this was necessary because the main goal of the authorities has been the maximization of recruitment, which this narrative was seen to support. The heroization was supported by providing returning war participants frequent opportunities to appear in public as role models (including in educational and childcare institutions), but also by the awarding of titles. As of July 2025, the Russian government awarded the “Hero of Russia” decoration to 459 people. This title also comes with elevated payments (more than 89,000 rubles monthly) from the federal budget.[101]

The Kremlin’s main vehicle to offer some, typically carefully selected, war participants a pathway to becoming part of the lower-level administrative elite has been the “Time of Heroes” program and its regional equivalents. The report discussed the results and limitations of these programs above.

Another means to make good on the promise of making war participants into a new elite has been their promotion to run as candidates in regional elections. Russian political parties—above all, United Russia—nominated more than 1,600 war participants in regional elections in September 2025. Of them, 1,035 were elected according to official figures, mostly as ruling party candidates, which, on the surface, is a significant growth from just 329 a year prior.[102] However, it is still only a sliver of the more than 47,000 positions that were up for election. It is worth noting that most successful candidates were elected to local positions without any meaningful power, and not regional legislatures, which have been important conflict resolution and interest representation grounds for local elites. This however would still make them stakeholders in the ongoing debate about the reform of municipal administrations that would see many lower-level assemblies scrapped.[103]

The nomination of war participants itself has been hindered by pushback against such candidates in several regions by existing party elites over the past years.[104] Although there were no such scandals in the latest 2025 election cycle, the ruling United Russia party’s decision to award a 25 percent bonus to war participants on every vote registered in its “primaries” suggests difficulties with mobilizing the party’s electorate for war participants simply by highlighting their background. In March 2025 journalist Farida Rustamova reported that the Kremlin was planning to have 100 war participants elected to the State Duma in the 2026 legislative election.[105] In October, however, the Kremlin was reportedly still surveying voters’ attitudes towards returning war participants as political candidates, for fear of the returnees’ appearing unpalatable to voters.

One of two outpatient clinics opened in December 2025 in Crimea. (Ministry of Health/VK)

Nonetheless, officials have been steadily appointing war participants to unelected positions in regional and municipal governments, organizations, and legislative assemblies, with dozens of appointments recorded in 2024–25, typically to positions that can be described as adviser, deputy overseer, or responsible for social outreach.[107] These appointments are often a way for governors to signal to the federal center that they are following the official line, without ceding actual power to appointees who continue depending on the support of established elites: e.g., in the case of Vologda governor Georgy Filimonov, one of the most ardent exponents of the Kremlin’s ultraconservative and pro-war policies, hinting that he would appoint war participants to head districts in his region, at a time when there are rumors about his imminent dismissal.[108]

Often returnees in these positions are tasked to oversee the implementation of policies regarding war participants. The purpose is likely dual: both to imply that returnees have officials to turn to who had experiences similar to them and to have war participants be the first point of contact for—and the target of potential dissatisfaction from the part of—other war participants.

From the Kremlin’s point of view, elevating the position of war participants has not only served the purpose of making it easier to recruit more war participants for financial and status gain; it has also served as a way to demonstrate new societal norms that both the population at large and elites must observe. By extolling the supposed virtues of war participants, the Kremlin is designating citizens voicing anti-war opinions as deviants and keeping officials on their toes, as they are aware that they can be replaced with someone more loyal-acting—as long as it is believable to a critical mass that, if it is necessary, the authorities are able and willing to enforce these norms.

Passively, the enforcement of this norm has been largely successful over the past three years, in spite of a steady series of active resistance against the Kremlin’s war narratives. This however does not mean that the Russian population accepts the Kremlin’s “new elite” narrative, especially when it comes to citizens who have first-hand experience with returning war participants. A 2025 survey by the Levada Center suggests that, in spite of the ongoing lionization of war participants, public opinion remains divided on the image of the returning soldier. Levada helpfully contrasts the findings with a survey of public perception of Afghanistan war veterans in 1990, albeit this was conducted after the end of that war and in an altogether freer public environment, so the comparison should be interpreted with reservations. Levada suggests that, in contrast to the veterans of the war in Afghanistan, somewhat fewer people regard war participants as victims (50 vs. 41 percent), while significantly more regard them as “resilient and courageous” (15 vs. 43 percent).[109]

Notably, more than twice as many of those surveyed said that the war had made soldiers more indifferent and cynical, and more prone to violence (11 and 19 percent, respectively) than did in 1990 about the “afgantsy.” Given the strict policing of the portrayal of the war in the public sphere, which has encouraged a culture of denunciations and allows the authorities to punish virtually anyone for “spreading fake information about the army,” it is likely that these perceptions stem from responders’ first-hand experiences. Indeed, the Levada survey itself measured an almost even split between those who said that the end of the war would bring more stability to Russia and those who think that the return of war participants would lead to an increase in crime and other conflicts, which, as laid out above, is a visible and tangible consequence of the war in several regions, even as the vast majority of soldiers have not yet returned from the front.[110]

The results also line up with a 2024 survey of the Khroniki collective, which found that 65 percent of Russians believed that economic gain played a role in the motivation of Russians who signed up to serve in Ukraine, with 37 percent identifying this as the only motivation.[111] This is also unsurprising: Flashy recruitment advertisements have been ubiquitous on the streets of Russian cities as well as online for the past two years, especially as regional governments and, in some cases, large employers were tasked to find people willing to help the military make up the numbers in Ukraine, with the help of constantly growing recruitment bonuses.[112] However, as a report by the Public Sociology Lab, a unique research project carrying out in-depth research across Russia to monitor attitudes about the war, pointed out, citizens show understanding towards these motivations, especially because they do not regard returnees as heroes, but humans. Much of the grassroots volunteer activity in support of the “special military operation” and soldiers has also been driven by a desire to help “one’s own people” rather than identification with Russia’s war aims, as the report evocatively described.[113]

This means that if it is needed, the Kremlin and regional leaders will likely be able to count on this solidarity reserve as an extension of or substitute for state efforts to help with the reintegration of returning soldiers. But this may run counter to the Kremlin’s narrative of a “new elite.” It also foreshadows frictions, as the authorities’ default attitude towards grassroots initiatives and organizations has been suspicion, suggesting that the authorities will likely prioritize co-opting local initiatives or hindering them if they are deemed to be political, a term up to the ever-changing interpretation of the authorities themselves.[114]

There has not been a lot of indication whether the attitudes of returning war participants towards the authorities and the issues defining local, regional and federal politics put them on the same platform as nationalist opinion leaders, pro-Kremlin political forces, civil society organizations such as those representing the wives and mothers of mobilized soldiers, or others.

Over the past year, amidst the debates around the reform of municipal administrations that aimed to eliminate lower-level institutions of self-governance, several war participants expressed frustration with the plans in multiple regions, e.g., the Kostroma Region and the Krasnoyarsk Territory.[115] This was not an issue specifically related to veterans; a very wide array of citizens and local administrative elites has raised their voices against these changes, which in many regions directly impact the accessibility of government services and thus standards of living, but it is worth noting that many war participants did not hesitate to express critical opinions on what was seen as a widely important issue.

One important question is whether, and when, returning war participants will decide that, as an important or privileged group of individuals, they are entitled to having their opinions and demands taken into account by the authorities. So far such events appear to have been isolated or kept under wraps, but they do periodically appear in the news. A report of the Agentstvo media outlet from a meeting of returnees in Siberia in October 2025 noted that war participants had criticized both the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, and propagandist Vladimir Solovyov in the presence of Tomsk governor Vladimir Mazur and Anatoly Seryshev, the Kremlin’s plenipotentiary in Siberia.[116] This is not surprising, given the frequency of mobilized soldiers’ video petitions to the Kremlin over lacking supplies in the period after the September 2022 mobilization.

Conclusions

Reintegrating war participants into civilian life will put a significant burden on both federal and lower-level budgets in Russia, as well as on large employers. On the whole, regional governments and budgets will likely have to take on political responsibility for the implementation of reintegration policies, even though in most cases the social infrastructure operated by them lacks the capacity to deal with the expected magnitude of the problem. Both federal and regional governments will likely attempt to pass on part of the financial burden of these policies to employers. The Kremlin will supervise and coordinate this work by defining standards and, in select cases, providing funding, while taking credit for cases of successful reintegration, which will likely be highly promoted in the media controlled by the authorities. However, the main risk is not the unavailability of funding, but the lack of capacity of the state to deliver social and medical services.

War participants returning to wealthier and poorer regions will likely have access to different standards of support, in many cases falling short of the care and the opportunities that the authorities have promised to them in order to increase and maintain their willingness to sign up for army duty and fight in Ukraine. Additionally, the vast majority of war participants will likely not have access even to the newly created promotion pipelines to the administrative elite, most of which are currently maintained for the use of people with pre-existing administrative experience, and will also have to adapt to lower incomes. Depending on the evolution of federal and regional regulation, certain categories of war participants (e.g., private military company recruits or members of territorial defense forces) may not have access to some of the benefits received by contract soldiers or mobilized troops. Frustration over the perception that some people have received the badge of “war participant” without actually taking part in fighting is already noticeable in pro-war populist media.[117]

War participants are currently a political brand, but not yet a political class or a political force. As a brand they and their needs affect the political context in which Russian officials have to act; however, due to their overall heterogeneity and a lack of coherent, independent structures to represent their interests, they cannot yet put institutional pressure on the authorities. They will also likely return to a country with still-escalating domestic repression, unlike the veterans of the war in Afghanistan. Maintaining the current distinction between “elite” veterans and others could breed frustration. However, over time the appointment of more “conventional” veterans to administrative positions may contribute to the development of a feeling of importance and entitlement regarding local or even federal politics.

The Kremlin’s objective is to keep communication with and between former war participants under the tightest possible control. For this purpose, the authorities are by default suspicious or in some cases hostile towards grassroots organizations that they cannot co-opt and veterans’ organizations that can challenge the Kremlin’s master narrative about the war in Ukraine. As long as the federal and regional authorities control the allocation of resources and access to services, many civil society initiatives may feel that close cooperation with the authorities is a more useful outcome than trying to circumvent them. The Kremlin can draw on more than just federal, regional, and local budgets to provide for returnees if needed.

Lastly, the exact shape and size of Russia’s postwar economic recovery will greatly depend on the withdrawal of Western sanctions. The opportunities and financial space created by this economic recovery will impact the efforts needed to reintegrate returning war participants into civilian life. This is one of the potential pressure points that Western powers supporting Ukraine can use in negotiations with the Kremlin.

Image credit: Artem Priakhin/SOPA Images

[1] “Heroes and villains: Russia braces for eventual return of its enormous army,” Reuters, September 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/heroes-villains-russia-braces-eventual-return-its-enormous-army-2025-09-09/.

[2] “Ikh ubili ‘veterany SVO’” [They were killed by the ‘veterans of the SMO’], 7×7, February 24, 2025, https://semnasem.org/articles/2025/02/24/ih-ubili-veterany-svo.

[3] Mark Galeotti, “Trouble at home: Russia’s looming demobilization challenge,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, June 2025, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Mark-Galeotti-Trouble-at-Home-Russias-looming-demobilization-challenge-GI-TOC-June-2025.pdf.

[4] “Putin nazval chislennost’ nakhodyashchikhsya v zone SVO boĭtsov armii Rossii” [Putin named the number of Russian army personnel in the SMO zone], Izvestiya, September 18, 2025, https://iz.ru/1957245/2025-09-18/putin-nazval-chislennost-nakhodiashchikhsia-v-zone-svo-boitcov-armii-rossii.

[5] Anfisa Dubrovskaya, “Stalo izvestno kolichestvo vernuvshikhsya s SVO rossiĭskikh voyennykh” [The number of Russian soldiers having returned from the SMO became known], Gazeta.Ru, June 26, 2025, https://www.gazeta.ru/army/news/2025/06/26/26131706.shtml.

[6] “Poteri Rossii v voĭne s Ukrainoĭ” [Russia’s losses in the war in Ukraine], Mediazona, updated November 7, 2025, https://zona.media/casualties.

[7] Sonya Savina, Yegor Feoktistov, and Polina Uzhvak, “Tri goda mobilizatsii: chto perezhil odin region — i vmeste s nim vsya strana” [Three years of mobilization: what one region went through — and with it, the whole country], Vazhnyye Istorii, September 19, 2025, https://istories.media/stories/2025/09/19/tri-goda-mobilizatsii-chto-perezhil-odin-region-i-vmeste-s-nim-vsya-strana/.

[8] “Tri goda zhalob, chetyre trupa. Kak vlasti ne spravilis’ s maroderstvom i napadeniyami voyennykh v prigranichnykh regionakh” [Three years of complaints, four corpses], 7×7, November 5, 2025, https://semnasem.org/articles/2025/11/05/maroderstvo-v-prigraniche.

[9] Sergeĭ Goryashko, “‘Vremya geroyev’. Kak voyevavshikh v Ukraine grabyat, b’yut i ubivayut v Rossii” [‘Time of Heroes’. How fighters of [the war in] Ukraine rob, beat and kill in Russia], BBC Russian, July 3, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/russian/articles/czdv0nq452jo.

[10] “Boleye 750 zhertv: kak vernuvshiyesya v Rossiyu uchastniki voĭny v Ukraine snova ubivayut i kalechat” [More than 750 victims: how returning soldiers of the war in Ukraine kill and maim again], Vërstka, February 24, 2025, https://verstka.media/kak-vernuvshiesya-v-rossiyu-uchastniki-voiny-v-ukraine-snova-ubivayut-i-kalechat.

[11] Kateryna Denisova, “Russia has recruited up to 180,000 convicts for war against Ukraine, Foreign Intelligence Service says,” Kyiv Independent, January 3, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/russia-recruits-up-to-180-000-convicts-for-war-against-ukraine-foreign-intelligence-service-says/.

[12] “Yekaterina Trifonova, “Tyuremnoye naseleniye prodolzhayet ischezat” [Prison population keeps declining], Nezavisimaya Gazeta, February 26, 2025, https://www.ng.ru/politics/2025-02-26/1_9201_prisoners.html.

[13] “‘Vozyat pryamo na pozitsii’: kak rossiĭskiye soldaty upotreblyayut narkotiki na voĭne” [‘They deliver it straight to the positions’: how Russian soldiers are using narcotics in the war], Vërstka, September 28, 2023, https://verstka.media/kak-rossiyskie-soldaty-upotrebliayut-narkotiki-na-voyne.

[14] Tat’yana Akinshina and Anastasiya Nikushina, “SVO, kotoraya vsegda s toboĭ. Kak rossiĭskiye voyennyye spravlyayutsya s PTSR” [SMO that is with you forever. How Russian soldiers are coping with PTSD], Ostorozhno Media, June 20, 2024, https://ostorozhno.media/shellshock/.

[15] V. A. Maslov, “Vliyaniye spetsial’noĭ voyennoĭ operatsii na prestupnost’ v Rossii” [The Impact of a Special Military Operation on Crime in Russia], Lex Russica 78, no. 3 (2025): 98–119, https://doi.org/10.17803/1729-5920.2025.220.3.098-119, mirrored at https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vliyanie-spetsialnoy-voennoy-operatsii-na-prestupnost-v-rossii/viewer.

[16] “Defenders of Fatherland State Foundation established to Support Participants in Special Military Operation,” President of Russia, April 3, 2023, http://en.kremlin.ru/acts/news/70823.

[17] Tat’yana Romanova, ed., “Alekseĭ Dyumin i Igor’ Babushkin nazvali zadachi novoĭ komissii Gossoveta” [Alexei Dyumin and Igor Babushkin named the tasks of the State Council’s new committee], Lenta.ru, March 19, 2025, https://lenta.ru/news/2025/03/19/aleksey-dyumin-i-igor-babushkin-nazvali-zadachi-novoy-komissii-gossoveta/.

[18]“‘Veterany SVO’ poluchayut innovatsionnyye kolyaski i sotszhil’ye, poka obychnyye lyudi ne mogut dozhdat’sya takoĭ pomoshchi. Kak rabotayet fond ‘Zashchitniki Otechestva’” [‘SMO veterans’ are getting innovative strollers and social housing while such aid does not reach regular people], 7×7, July 24, 2025, https://semnasem.org/articles/2025/07/24/kak-rabotaet-fond-zashitniki-otechestva.

[19] “Proyekt ‘Put’ veterana SVO’ startuyet v Arkhangel’skoĭ oblasti” [The ‘Road of the Veteran’ project is starting in the Arkhangelsk Region], RIA Novosti, July 1, 2025, https://ria.ru/20250701/arkhangelsk-2026485976.html.

[20] Sonya Aĭzenberg, “‘Vse, chto nam obeshchali, — lozh’. Komu i zachem nuzhen fond ‘Zashchitniki Otechestva’” [‘Everything that we were promised was a lie’. Who needs the ‘Defenders of the Fatherland’ fund and why?], Sever.Realii, February 28, 2024, https://www.severreal.org/a/vse-chto-nam-obeschali-lozh-komu-i-zachem-nuzhen-fond-zaschitniki-otechestva-/32832488.html.

[21] Anastasiya Maĭyer, “Fond ‘Zashchitniki Otechestva’ raspredelil vydelennyye pravitel’stvom 1,314 mlrd rubleĭ” [The ‘Defenders of the Fatherland’ fund distributed 1.314 billion rubles received from the government], Vedomosti, June 19, 2023, https://www.vedomosti.ru/society/articles/2023/06/19/981074-fond-zaschitniki-otechestva-raspredelil-videlennie-pravitelstvom.

[22] “Na fond plemyannitsy Putina potratyat v 2025 godu v 2,5 raza bol’she zaplanirovannogo” [In 2025 2.5 times more money will be spent on the fund of Putin’s cousin than was planned], Agentstvo, September 29, 2025, https://www.agents.media/na-fond-plemyannitsy-putina-potratyat-v-2025-godu-v-2-5-raza-bolshe-zaplanirovannogo/.

[23] “Vyplaty i l’goty uchastnikam SVO: kakiye yest’, kto imeyet pravo, kak poluchit’” [Payments and breaks for SMO participants: what kinds are there, who has rights to them, and how to get them], RIA Novosti, January 23, 2025 (updated November 10, 2025), https://ria.ru/20250123/svo-1985822676.html.

[24] From hundreds of thousands to several million rubles, seе “Regional’nyye vyplaty pri zaklyuchenii kontrakta uchastnikam SVO v 2025 godu” [Regional payments to SMO participants upon signing a contract in 2025], Zashchitnik.rf, https://защитник.рф/blog/regionalnye-vyplaty-uchastnikam-svo. The circle of recipients can also differ; see, e.g., St. Petersburg: Ran’she vsekh. Nu pochti (@bbbreaking), “V Peterburge vyplaty za raneniya na SVO budut rasprostraneny na uchastnikov ChVK” [In St. Petersburg payments for injuries suffered in the SMO will be distributed to PMC members], Telegram, July 1, 2025, https://t.me/bbbreaking/210197; Chelyabinsk: UralInfoZavod (@uralinfozavod), “V Chelyabinskoĭ oblasti rasshiryat spisok poluchateleĭ vyplat za SVO” [The list of those eligible for SMO payments will be broadened in the Chelyabinsk Region], Telegram, March 24, 2025, https://t.me/uralinfozavod/1526.

[25] “Regional’nyye vyplaty pri zaklyuchenii kontrakta uchastnikam SVO v 2025 godu” [Regional payments to SMO participants upon signing a contract in 2025], Zashchitnik.rf, https://защитник.рф/blog/regionalnye-vyplaty-uchastnikam-svo; “O vnesenii izmeneniĭ v Federal’nyĭ zakon ‘Ob ispolnitel’nom proizvodstve’ i Federal’nyĭ zakon ‘Ob osobennostyakh ispolneniya obyazatel’stv po kreditnym dogovoram (dogovoram zaĭma) litsami…” [About introducing amendments to the Federal Law ‘On enforcement proceedings’ and the Federal Law ‘On the particularities of enforcing obligations in credit agreements’], No. 667894–8, State Duma, November 20, 2024, https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/667894-8.

[26] “Dlya uchastnikov SVO i chlenov ikh semeĭ rasshiren perechen’ nalogovykh l’got” [The list of tax breaks for SMO participants and their relatives has been widened], Federal Tax Service of Russia, February 28, 2025, https://www.nalog.gov.ru/rn92/news/activities_fts/15871518/.

[27] “Dlya uchastnikov SVO i chlenov ikh semeĭ rasshiren perechen’ nalogovykh l’got.” [The list of tax breaks for SMO participants and their relatives has been widened], Federal Tax Service of Russia, February 28, 2025, https://www.nalog.gov.ru/rn92/news/activities_fts/15871518/.

[28] “Postanovleniye Pravitel’stva Rossiĭskoĭ Federatsii ot 25.12.2024 No. 1893 ‘O vnesenii izmeneniĭ v nekotoryye akty Pravitel’stva Rossiĭskoĭ Federatsii’” [Resolution of the Government of the Russian federation from December 25, 2024 no. 1893, ‘On introducing amendments in certain acts of the Government of the Russian Federation], Ofitsal’noye opublikovaniye pravovykh aktov, December 27, 2024, http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/document/0001202412270098.

[29] For a detailed collection of regional support for war goals, including support measures benefiting war participants, and the differences between regions, see: “Vovlechennost’ sub”yektov Rossiĭskoĭ Federatsii v povestku Spetsial’noĭ voyennoĭ operatsii” [Involvement of the subjects of the Russian Federation in the agenda of the Special Military Operation], Tsentr Politicheskoĭ Informatsii, March 6, 2025, https://polit-info.ru/images/data/gallery/0_4639_vovlechennost_svo.pdf.

[30] “Detyam, nuzhdayushchimsya v osoboĭ zabote gosudarstva” [For children who need the special care of the state], Ministerstvo Sotsial’noĭ Politiki Lipetskoĭ Oblasti, https://usp.admlr.lipetsk.ru/iblock/socpodderjka/sanatornokurortnie_putjovki/e/detjam_nuzhdajushhimsja_v_osoboj_zabote_gosudarstva/; “V Arkhangel’skoĭ oblasti sem’i uchastnikov SVO osvobodyat ot uplaty transportnogo naloga” [In the Arkhangelsk Region families of SMO participants will be free of paying transit tax], Vedomosti, August 29, 2025, https://spb.vedomosti.ru/society/news/2025/08/29/1135051-arhangelskoi-oblasti-semi-uchastnikov-svo-osvobodyat-ot-uplati-transportnogo-naloga; Dmitriĭ Makhonin (@mahonin59), “Krayevyye parlamentarii podderzhali neskol’ko vazhnykh dlya zhiteleĭ regiona initsiativ” [Regional parliamentarians supported a number of initiatives important for the residents of the region], Telegram, May 22, 2025, https://t.me/mahonin59/9265; Aleksandr Moor (@av_moor), “Yeshche odna mera podderzhki sem’yam uchastnikov SVO vvoditsya v Tyumenskoĭ oblasti” [The Tyumen Region will introduce yet another measure to support the families of SMO participants], Telegram, April 17, 2025, https://t.me/av_moor/4547; Parfenchikov|Kareliya (@AParfenchikov), “Vnës zakonodatel’nuyu initsiativu ob otmene transportnogo naloga dlya uchastnikov SVO” [I introduced a legislative initiative to scrap transit tax for SMO participants], Telegram, March 14, 2025, https://t.me/AParfenchikov/5911.

[31] Dmitriĭ Makhonin (@mahonin59), “Molodyye sem’i uchastnikov SVO smogut poluchat’ vyplaty na pokupku zhil’ya v pervuyu ochered’” [Young families of SMO participants will be able to get support to buy apartments in the first place], Telegram, February 6, 2025, https://t.me/mahonin59/8127; and Marat Betanov (@MaratBetanov), “Segodnya u nas vazhnaya novost’” [We have important news today], Telegram, October 23, 2025, https://t.me/MaratBetanov/40.

[32] The Government of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous District, “Mery sotspodderzhki uchastnikam SVO i chlenam ikh semeĭ” [Social support measures for SMO participants and their family members], https://svo.admhmao.ru/

[33] See, e.g., Rostov: Yuriĭ Slyusar’ (@Yuri_Slusar), “Yeshche odno vazhnoye resheniye po itogu priyema uchastnikov SVO” [Another important decision based on receiving SMO participants], Telegram, April 23, 2025, https://t.me/Yuri_Slusar/2040; Sverdlovsk: Denis Pasler (@DVPasler), “Rasshiryayem mery podderzhki dlya uchastnikov SVO i ikh semeĭ” [We are broadening support measures for SMO participants and their families], Telegram, October 22, 2025, https://t.me/DVPasler/5503; Kursk: Aleksandr Khinshteĭn (@Hinshtein), “Vnës v oblastnuyu Dumu zakonoproyekt, rasshiryayushchiĭ pravo na polucheniye besplatnogo zemel’nogo uchastka veteranami SVO” [I introduced to the regional Duma a bill, which will broaden SMO participants’ rights to receive free land lots], Telegram, April 24, 2025, https://t.me/Hinshtein/11221; and Stavropol: Vladimir Vladimirov (@VVV5807), “Rasshiryayem mery podderzhki dlya uchastnikov SVO” [We are broadening support measures for SMO participants], Telegram, July 17, 2025, https://t.me/VVV5807/4432.

[34] “Vyplaty i l’goty uchastnikam SVO: kakiye yest’, kto imeyet pravo, kak poluchit’”; [Payments and breaks for SMO participants: what kinds are there, who has rights to them, and how to get them], RIA Novosti, January 23, 2025 (updated November 10, 2025), https://ria.ru/20250123/svo-1985822676.html; Pervyĭ Arkticheskiĭ (@first_arctic), “V Yamalo-Nenetskom avtonomnom okruge dlya uchastnikov SVO rasshirili vozmozhnosti ispol’zovaniya regional’nykh vyplat” [In the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District SMO participants’ opportunities to use regional payments has been broadened], Telegram, August 27, 2025, https://t.me/first_arctic/11622.

[35] See, e.g., Tambov: Diana Yashina, “V regione dlya uchastnikov SVO i ikh semeĭ vveli vyplatu na pokupku uglya ili drov” [Payments to buy coal or firewood have been introduced in the region for SMO participants and their families], Top68, October 29, 2025, https://top68.ru/news/society/2025-10-29/v-regione-dlya-uchastnikov-svo-i-ih-semey-vveli-vyplatu-na-pokupku-uglya-ili-drov-303393; Kamchatka: Macho s Avachi Z (@kamchatskymacho), “Na Kamchatke uchastnikam SVO, kotoryye zhivut v chastnykh domakh bez tsentral’nogo otopleniya…” [In Kamchatka SMO participants who live in detached houses without central heating…], Telegram, October 10, 2025, https://t.me/kamchatskymacho/8142; Transbaikal: Nikita Kondrat’yev, “Kompensatsiyu za drova v Zabaĭkal’ye uvelichili do 22 tysyach rubleĭ” [Compensation for firewood has been increased to 22 thousand rubles], Zab.ru, September 22, 2025, https://zab.ru/news/189826; Ingushetia (for gasification): Makhmud-Ali Kalimatov (@MAKalimatovvv), “V Ingushetii my pridayem osoboye znacheniye podderzhke uchastnikov SVO i ikh semeĭ” [In Ingushetia we attach special significance to the support of SMO participants and their families], Telegram, July 24, 2025, https://t.me/MAKalimatovvv/9162; Jewish Autonomous Region: EAO (@EAOplus), “Poluchat’ vyplatu na priobreteniye tverdogo topliva smogut sem’i uchastnikov SVO v EAO” [In the JAR the families of SMO participants will be able to receive payouts to acquire firewood], Telegram, January 7, 2025, https://t.me/EAOplus/1301.

[36] Stavropol: Vladimir Vladimirov (@VVV5807), “Rasshiryayem krayevuyu podderzhku uchastnikov SVO” [We are broadening regional support measures for SMO participants], Telegram, September 25, 2025, https://t.me/VVV5807/4910; Jewish Autonomous Region: Mariya Kostyuk (@kostuyk), “Chat moyego telegram-kanala ostayetsya odnoĭ iz glavnykh ploshchadok dlya kommunikatsii s zhitelyami” [The chat of my Telegram channel remains one of the main places to communicate with residents], Telegram, March 17, 2025, https://t.me/kostuyk/7871; and Mariya Kostyuk (@kostuyk), “V preddverii novogo uchebnogo goda prinyali resheniye vvesti dopolnitel’nuyu meru podderzhki dlya semeĭ nashikh Geroyev” [At the beginning of the new schoolyear a decision was adopted to introduce additional support measures for the families of our heroes], Telegram, August 8, 2025, https://t.me/kostuyk/9242; Pskov: Mikhail Vedernikov (@MV_007_Pskov), “V Izborske ko mne obratilas’ mestnaya zhitel’nitsa s pros’boĭ skorrektirovat’ otdel’nyye polozheniya mer podderyhki semeĭ uchastnikov SVO” [In Izborsk a local resident addressed me with a request to correct the specific provisions of support measures for the families of SMO participants], Telegram, February 5, 2025, https://t.me/MV_007_Pskov/6122; Lipetsk: Igor Artamonov (@igor_artamonov48), “K nachalu novogo uchebnogo goda sem’i nashikh uchastnikov spetsial’noĭ voyennoĭ operatsii poluchat yedinovremennuyu vyplatu” [For the beginning of the schoolyear the families of our participants of the special military operation will receive a one-time payment], Telegram, August 22, 2025, https://t.me/igor_artamonov48/5083; Tula, Tul’skaya oblast’ (@tularegion71), “Soberi rebyonka v shkolu” [Get your child ready for school], Telegram, August 18 2025, https://t.me/tularegion71/21546; and Perm: Dmitriĭ Makhonin (@mahonin59), “Regulyarno rasshiryayem mery sotsial’noĭ podderzhki semeĭ” [We regularly broaden social support measures for families], Telegram, October 2, 2025, https://t.me/mahonin59/10553.

[37] “Glava Stavropol’ya poruchil pomogat’ veteranam SVO v vosstanovlenii biznesa” [The head of Stavropol ordered to help SMO veterans restore businesses], BezFormata, March 19, 2025, https://stavropol.bezformata.com/listnews/biznesa/143842171/.

[38] Yevgeniĭ Solntsev (@solntsev_official), “Trudoustroĭstvo, sotsializatsiya veteranov SVO” [Employment and socialization of SMO veterans] Telegram, https://t.me/solntsev_official/4007, Telegram, October 24, 2025; and Il’ya Seredyuk (@ilyaseredyuk), “Zapustili novuyu meru podderzhki dlya uchastnikov SVO i chlenov ikh semeĭ” [New support measures have been launched for SMO participants and their families], Telegram, April 23, 2025, https://t.me/ilyaseredyuk/5055.

[39] Klub Regionov (@clubrf), “Vopros adaptatsii uchastnikov SVO k mirnoĭ zhizni ostayetsya odnoĭ iz samykh vazhnykh zadach dlya gubernatorov” [The issue of the adaptation of SMO participants to civilian life remains one of the most important tasks of governors], Telegram, October 20, 2025, https://t.me/clubrf/41572.

[40] “Vyplaty i l’goty uchastnikam SVO: kakiye yest’, kto imeyet pravo, kak poluchit’” [Payments and breaks for SMO participants: what kinds are there, who has rights to them, and how to get them], RIA Novosti, January 23, 2025 (updated November 10, 2025), https://ria.ru/20250123/svo-1985822676.html.

[41] Yuliya Maleva, “Regiony nachnut shtrafovat’ rabotodateleĭ za otsutstviye kvot dlya uchastnikov spetsoperatsii” [Regions will start fining employers for the non-observation of special military operation quotas], Vedomosti, August 15, 2025, https://www.vedomosti.ru/society/articles/2025/08/15/1131737-regioni-nachnut-shtrafovat-rabotodatelei-za-otsutstvie-kvot-dlya-uchastnikov-spetsoperatsii.

[42] See, e.g., Karelia: Parfenchikov|Kareliya (@AParfenchikov), “V Karelii dlya veteranov SVO budet ustanovlena kvota dlya priyëma na rabotu” [In Karelia employment quotas will be introduced for SMO veterans], Telegram, June 23, 2025, https://t.me/AParfenchikov/6523.

[43] Mel’nichenko (@omelnichenko), “Na zasedanii pravitel’stva Penzenskoĭ oblasti poprosil rukovoditeleĭ gorodov i raĭonov vzyat’ pod osobyĭ kontrol’ rabotu po vaktsinatsii ot grippa” [At a meeting of the government of the Penza Region I asked city and district leaders to take flu vaccination under personal control], Telegram, September 26, 2025, https://t.me/omelnichenko/6966.

[44] “Kvoty po trudoustroĭstvu dlya veteranov SVO” [Quotas for the employment of SMO veterans], Prizyv, September 9, 2025, https://priziv.online/vazhnoe/2025/09/07/kvoty-po-trudoustrojstvu-dlya-veteranov-svo/.

[45] Denis Pasler (@DVPasler), “Rebyata, vernuvshiyesya ‘iz-za lentochki’, mogut uspeshno realizovat’ sebya v Sverdlovskoĭ oblasti” [The guys returning ‘from out there’ will be able to build success in the Sverdlovsk Region], Telegram, October 3, 2025, https://t.me/DVPasler/5404.