A nation must think before it acts.

Natalia Kopytnik: Hello, everyone. My guest today is Dr. Māris Andžāns, the director of the Center for Geopolitical Studies in Riga.

Dr. Andžāns has over ten years of public service experience serving in a variety of positions related to EU and NATO issues, civil-military cooperation, and communications, among many others.

Māris, thank you so much for joining me today on The Ties That Bind and for welcoming us into your office in the beautiful old city Riga.

Māris Andžāns: Yes, thanks for coming down. Looking forward to our conversation.

NK: So I think for starters, we have to set the scene, right? Because we are in Riga today, as I mentioned, and it’s only about 300 kilometers from the Russian border.

It feels like there’s nowhere else that the generational contest between Russia and the West plays out more than in the Baltic States, on every level. And I think the events that have been happening in the skies over Europe in the last few weeks have really only heightened that awareness. But it feels like Latvians have been acutely aware of these threats and have been preparing for them for a long time.

So, you wrote, actually, about Latvia’s experience with the drone incursion last year for FPRI. As you pointed out, Russian drones and missiles entering NATO territory, it’s not really an extraordinary event anymore. But this last month has really felt like a shift in the response, especially from NATO.

Could you tell us a little bit about what the Latvian sentiment and response has been to this evolving security situation after all these suspicious drone sightings at airports after the drone incursions in Poland, Romania, the airspace violations in Estonia? Is there a sense that this is business as usual in this part of the world? Or is there a sense that things are escalating? And do you feel like Latvians are confident in their own defense and NATO defense capabilities in light of all of this?

MA: So, maybe for context, Latvia gained independence in 1991, and basically since then, relations with Russia have been quite complicated.

Russia withdrew its armed forces only in 1994. Then, Latvia quickly did everything it could to join NATO. We joined NATO in 2004, and over the three decades and a bit more, we’ve seen many interactions with Russians. Obviously, the war in Ukraine in 2022 was a large geopolitical shock for Latvians. It was not only about the elites, but about the entire society, because many thought that Russia would also invade the Baltic States, because, during the first weeks of the war, it appeared that Ukraine might fall. That thankfully didn’t happen but people obviously have their fears here.

So, 2022 it was especially tough. So many people were worried, many prepared so-called emergency bags just in case they had to leave—[in them were] some basic things which you had to survive without electricity and so forth. And yeah, the three and a half years have been quite complex here. Russia has increased the level of subkinetic activities. Well, we’ve seen the drone incursions. One drone, the Shahed 136 type drone, landed in eastern Latvia with explosives. Nobody was hurt, but that was quite unfortunate.

Then we have seen various arson attacks here. Then, Russia’s Shadow Fleet cut communication and natural gas and electricity cables on the seabed in the Baltic Sea and sent drones. And then, fighter jets have violated Baltic airspace, also in conjunction with Belarus.

Russia has launched a weaponization of migration operations. So basically, they are inviting migrants from the Middle East and other regions to Belarus and Russia, and then they are guiding them towards Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. This also has created quite a dilemma for the Baltic States and Poland.

NK: You mentioned the drones, and unfortunately, the issue of drones is just becoming a permanent fixture in our vocabulary. Obviously, it’s the sad reality of millions of Ukrainians every night and in their own cities.

But over the past month, the EU and NATO have really started talking about creating a so-called drone wall to shore up defenses on the eastern flank. Now, the details are not clear, but predating all of this, Latvia has really been a leader on the drone front on the EU side. In 2024, I believe, Latvia, with the United Kingdom, formed the so-called drone coalition, which basically commits countries to having a steady supply of UAVs to Ukraine—I think it’s something like 30,000 this year.

Then, this past May, Latvia hosted the first drone summit [in Riga], which is really encouraging ties between the technology sector and government and collaboration on innovation in this, on the production of unmanned systems.

And then, you also have the creation of the drone Competence Center here in Riga to further educate the armed forces and integrate these systems into national defense.

Could you tell us a little more about the drone situation? How has it been that Latvia has really emerged as a leader on this front?

MA: Latvia indeed has been relatively good at PR when it comes to drones, because Latvia indeed established the Drone Coalition, so together with the United Kingdom, Latvia has gathered financial resources and then also drones that have been supplied to Ukraine.

And Latvia is investing more and more in drones. But on the other hand, obviously, there’s no better country than Ukraine when it comes to drones. And unfortunately, also Russia.

So, in that sense, it remains to be seen what would happen in actual circumstances because, well, there’s no cure yet for drone warfare. We saw the situation in Poland: Poland also was not able or chose not to down all of the drones that crossed into [it].

Latvia has good manufacturers when it comes to UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) but also unmanned ground systems and unmanned surface vehicles. But it remains to be seen how good and effective they are in combat situations. So, on the one hand a lot has been done, but I think there is still a large space for progress for Latvia. Not only us, we are not unique in this sense.

NK: So, as part of the commitments in the drone coalition, are the majority of the drones that Latvia is providing to Ukraine manufactured here in Latvia or is it just basically purchasing from other places? How does that work?

MA: Some come from Latvia, but others don’t, and I’ve heard mixed reactions from Ukraine. Ukrainians tell us, “Come on, we need money. We can produce drones more effectively, cheaper, and we are ahead in drone competence because things are changing quickly on the battlefield. It’s not 2022 anymore.”

Production only started. So now I have fiber optic drones and Ukrainians have quite good electronic warfare capabilities, but Russians are also advancing. So the Shahed drones that were dispatched from Russia early in the war are completely different from those that we can see now. They use this swarm technology, they are avoiding jamming and picking up signals from mobile communication towers, and they fly faster, they fly higher.

So, there’s sort of a constant competition between one and the other, as a chief operating officer of one of the companies in Latvia involved in drone manufacturing [told us], “If you are not in Ukraine now, you are not relevant.”

And that is indeed the point. We have to learn from Ukraine, and also the Drone Coalition provides Latvia with the opportunity to learn more from Ukraine, from first-hand experience.

NK: I think it almost seems like with these projects, like the drone wall idea, do you feel like it’s almost too little too late? Latvia has obviously been one of the countries that has been thinking about this since prior to the last month, let’s say. Because the term drone wall really came up after the recent drone incursions in Romania and Poland.

Why do you think it’s taken so long for other European countries to realize that we don’t really have the capacity to effectively down drones in a cost efficient way? Because the systems that are used, for example, in Poland that were used to shoot down those drones cost millions of dollars, whereas the drones themselves are quite cheap, right? So you’re using very costly systems to shoot down relatively cheap drones.

Why do you think there’s been such a lag in thinking about not just innovation, but investment in this sector? As you pointed out, the drone environment has been evolving so rapidly, but it’s been at the forefront of all of these conversations about Russia’s war in Ukraine since 2022. We’re now in 2025, so it feels like it’s been a bit too slow, right?

MA: Indeed, and that’s a question that I have too. I have no definite answer, because obviously things work slightly differently in the military environment. So, things are very structured, and it takes time. You have to work between and among different national authorities, and it’s much harder during peacetime because you have to follow procurement rules and research on that.

And it’s much more difficult in a sense. It’s easier in Ukraine because some of the manufacturers here in Latvia tell us that basically if you are in war, you can stitch things together with plaster or with whatever. But here, everything has to be certified, tested. You have to undergo different compliance procedures. So it’s much more complicated.

But I agree with that point, that we have been too slow. It’s more than three and a half years into the war. Latvia has done a lot by improving its defenses, but still I think that the pace has been too slow. And that also is [true] regarding drones. I think that Latvia and other nations could have done more because drones were around before the war already many years ago. So, this was nothing new, and we should have done more. My version is that, indeed, it’s the modus operandi in military authorities: It’s not easy to adapt during peacetime, or at least when we think that we are at peace.

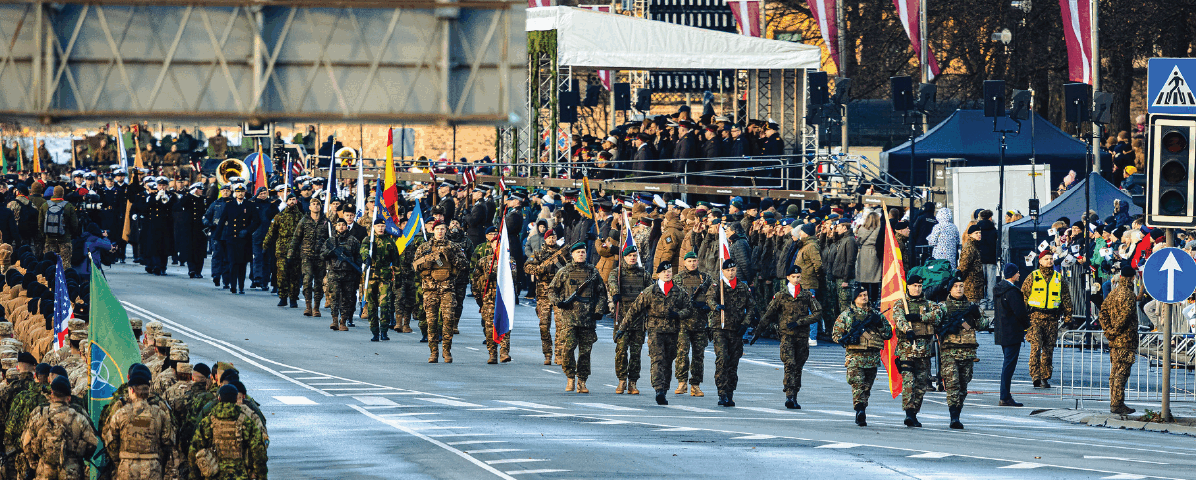

NK: When Russia seized Crimea in 2014, I think that really prompted NATO to think more about sending rotational units into the Baltic States more than before. And I believe it was last year that Latvia became the first country to scale up its NATO forward presence with the multinational brigade.

Can you talk a little bit more about what role this multinational brigade in Latvia has played in terms of NATO operations and thinking about Latvia’s own defense strategy?

MA: The arrival of NATO’s multinational battle group in 2017 was a game changer. Latvia joined NATO in 2004, and then basically became a NATO member state only on paper because there was only the Baltic air patrolling mission. So you usually had four fighter jets flying out of Lithuania and policing the skies of the Baltic States since neither Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania have fighter jets, and they probably won’t have [them] in the foreseeable future. So, basically we’ve had the only Baltic air policing mission.

When Russia occupied Crimea and started a war in eastern Ukraine, that was also alarming. And then the United States sent company-sized units in spring of 2014 to each of the Baltic States and also Poland. That was basically the first time when a rotational, but sort of permanent presence by NATO Allies was ensured in the Baltic States. Before we only had four four fighter jets, which was almost nothing. Not bad, but almost nothing.

In 2017, we received the Canadian-led battle group. At first it was a battalion-sized unit, but following the Madrid summit of NATO in 2022, it was scaled up to an entire brigade. So a brigade is obviously a lot better than a battalion, but it’s still not sufficient. And currently the brigade, the numbers, fluctuate because there are more than a dozen nations: Canadians lead it, and we have Spanish, Danish, Swedish soldiers, and many other nations.

And the numbers fluctuate, but basically it’s one brigade. It is really crucial that we have NATO Allies here, boots on the ground. First and foremost, it’s about deterrence so that Russia takes us seriously, because obviously if there are no Allied troops in the Baltic States, we are not among the strongest NATO Allies, we have basically no effective air force, we have helicopters, transport aircraft, only Lithuania has a medium-range Euro-defense system.

So it’s crucial that we have these Allies here. And apart from the NATO Multinational Battle Group, we also have Americans rotating here in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. This is really, really crucial because if we had not joined NATO, who knows, maybe we would have been in the place of Ukraine or we [would be] like a second Belarus here.

NK: One thing that I’ve been thinking about is how there has been, maybe disharmony is the wrong word, but certainly Europeans seem to be a little bit split about how to react to all of these recent aggressions and incidents. There’s been this push and pull between projecting strength but also the fear of stronger rhetoric and falling into the escalation trap.

So, naturally, Poland comes to mind in the in the first camp, projecting strength, being very kind of—I think a Polish foreign minister was quite blunt at the the UN General Assembly when he said if a Russian aircraft crosses into Polish airspace, whether it’s by accident or on purpose, “We’re shooting it down and don’t come here to whine about it.” I think that was the quote more or less.

But other countries, such as Germany, have been a lot more cautious and have been aiming to tone down the rhetoric.

So, in this context, where do you think Latvia falls? Is it more in the projecting strength front or is it more cautious, not falling into the escalation rhetoric?

MA: Well, the three Baltic States and Poland have been on the same page. We have always told the rest that you can’t trust Russia and that Russia respects only strength. And in return, we were often accused of being Russophobic, paranoid, and so forth. So, things have changed. They changed quite quickly after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia. So, things are a lot better now. Germans, they have also changed considerably. Germany currently leads a brigade in Lithuania, so it was quite complex for them to transform because the Bundeswehr (German forces) was not and still is not in the best shape, but they have done a lot.

You can criticize zeitenwende for not achieving everything. But then Chancellor Scholz promised that Germany has changed quite considerably and we’ve seen it here. So, they’re in Lithuania, and that also helps Latvia and Estonia and is very, very important for our region.

NK: I think one of the most impressive things for me when thinking about Latvia has always been its aid to Ukraine. And one always hears about the “small Baltic States.”

But actually, when thinking about Latvia’s aid to Ukraine over the past few years, proportionally, it is not small at all by any means. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think in 2022, Latvia donated almost 1 percent of its GDP towards aid to Ukraine, and it has been giving at similar levels since then. Of course, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland are also very much in that camp.

But at the same time, I feel like there’s this growing American ambivalence towards Europe, right? We see it in the statements of President Trump. We’ve seen the flip-flopping on how he’s talked about the war in Ukraine—don’t have to rehash all that. We’re all current on what’s going on there. America was giving aid to Ukraine but now, President Trump says that America is willing to sell but not donate weapons to Ukraine. And obviously, the elephant in the room here is America, the richest country in the world saying it will sell but it will not donate, whereas Latvia, a so-called small country is giving a sizable chunk of its GDP to Ukraine.

And just for context for listeners—I had to look this up because I knew it was going to be a big difference—Latvia’s GDP is about 43.5 billion dollars, whereas America’s is 30 trillion dollars.

How has this shift in America’s approach to the war been perceived domestically? Is it “Okay, well, at least they’re still going to sell us the weapons systems,” or is it more like “What’s going on here guys?”

And then, as a follow-up, looking at Latvia’s financial commitments to its defense to support Ukraine, the plans are to raise defense spending to 5 percent over the next few years. Are they sustainable going forward and into the next decade?

MA: Well, yeah, so when it comes to Latvia’s defense, Latvia has increased defense expenditure significantly.

As mentioned, Latvia joined NATO in 2004, and we entered an era of euphoria. So we thought that Russia was going to be a normal country, that it would Westernize, democratize, and so forth. And Latvia basically started slacking when it came to defense. We didn’t reach 2 percent of GDP spending for the first fourteen years of being members of NATO. Latvia reached 2 percent only in 2018.

In a way, Latvia thought “Everything’s going to be all right. We have Article 5 and the Allies will protect us.” So, Latvia was in a very bad shape. In 2014, Latvia’s armed forces were only around 5,300 soldiers; we spent some 220 million euros on defense only, which is less than 1 percent.

Now fast forward to 2025. This year, Latvia spent around 1.6 billion euros, which is around 3.8 percent of GDP, and Latvia is inching closer to 5 percent. Latvia will spend that soon, maybe already by next year.

And in our case, well, we have no other options. If you do not feed your army, you will be feeding another army, and so Latvia must spend more. And everyone understands—almost everyone, because obviously there are different voices around—but the society in general understands you have to spend on your defense because people understand that Ukraine is fighting for Latvia, for Europe, for NATO. So, Latvia is going to spend more and more on defense, and there’s simply no other way. And when it comes to the American position, well, we have not been satisfied for three and a half years already. Because previously, during the Biden administration, people criticized the United States for not doing enough, for not sending the right equipment, and for not doing more.

And now, obviously, we would have been much happier if the United States had continued the course of the Biden administration. Because, had Biden not helped Ukraine, who knows where the frontline would be now. And that would be very, very complex. So it is unfortunate, obviously, that America is not donating; it is only selling weapons to Ukraine. But at the same time, Americans are sharing intelligence, which also matters, assisting with logistics.

And we’ll see what comes next. But President Trump is right that there is one big beautiful ocean between the United States and Europe, and this is foremost our responsibility. So the Baltic States and Poland and many others are doing their best, but overall Europe could do more.

And from that other perspective, I can understand it very well. I have also been in the US, and it’s difficult to explain to people somewhere in the Midwest that there is a country called Ukraine, and Americans have to help to defend it. They have their own problems, and in that environment and similar environments, President Trump’s messages, they resonate.

NK: This is a good segue to the reflection part of the series. You mentioned a few things that I want to refer back to. You said when Latvia joined NATO in 2004, that it was a sense of euphoria, but also maybe a little bit of a complacency for a little bit—as you said, the Article 5 protection, feeling like, “Okay, we’ve made it.”

How do you assess Latvia’s 21 years now in NATO overall? And you mentioned what it meant then, but what does it mean now? And perhaps, in what areas do you feel like Latvia has really stood out as a leader in the context of NATO?

MA: Well, we were members of NATO for 21 years already, so [it has been] more than thirteen years since we gained independence and joined NATO. So basically, most of the time that we’ve been independent again, we’ve been members of NATO, and that matters a lot, as NATO is the backbone of Latvia’s defense. If there is no NATO, we have big, big problems. NATO enjoys quite high support among Latvia’s population.

And it is indeed the backbone of Latvia’s defense, as mentioned previously. We’re a small nation, and the armed forces have much room for progress. We have no medium-range and obviously also no long-range defense systems, no fighter jets. We all have only three helicopters: Black Hawks, American ones. The fleet is rather small, we have mostly patrol vessels and minesweepers.

And Latvia has done a lot, obviously, during the past decade, but with all that, we are still small and vulnerable. So that’s why NATO is indeed very important for NATO’s defense.

NK: And as you mentioned, sometimes, it’s harder for Americans to understand this. America is a huge country, very diverse, very geographically spread out, and sometimes it’s understandable that conflicts on the other side of the “big, beautiful ocean” are not on everyone’s minds.

But what would you like Americans to understand about Latvia’s role in transatlantic security as a whole, and why is preserving and being active in alliances like NATO so important for Allies on both sides of the ocean?

MA: It’s better to have more friends than less friends, and alliances have mutual benefits. Latvian soldiers have served both in Afghanistan and Iraq. Several Latvian soldiers have lost their lives and also received injuries. So, Latvia was there for the United States when Americans asked for Latvia’s involvement in those missions and others. Currently, Latvian soldiers serve in missions and operations around the globe. Kosovo currently is the biggest, but Latvian soldiers are also in Lebanon, some are also in Iraq, and in other places. This is one point, and obviously, we are happy to help Americans whenever we can. I also think that Latvian society is generally sympathetic towards Americans and America, and this is not the case in many other countries around the globe, so in general, it’s good to have other countries and societies that have positive views of your country.

NK: Definitely. Well, Māris, thank you so much for sharing your insights with us. And thank you so much for joining us on The Ties That Bind today.

Image: Flickr | Latvijas armija