A nation must think before it acts.

In the chill of early March, nearly 5,000 of China’s most important people gathered in Beijing for what are called the two meetings: the National People’s Congress (NPC), which is in theory the nation’s highest legislative body, and the Chinese People’s Consultative Conference (CPPCC), an organ of the Party’s United Front Work Department, which gives institutional form to the unity of all the country’s people under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Security, though was not nearly so tight as that preceding the 19th National Congress of the CCP in November 2017, nonetheless resulted in massive traffic jams at entry points to the city with arrivals screened by a facial recognition system. The People’s Armed Police monitored the entrances and exits to every subway station, and foreigners reported patchy disruptions in their internet access. Near the area of the two meetings, no mobile devices, including cell phones, were allowed.

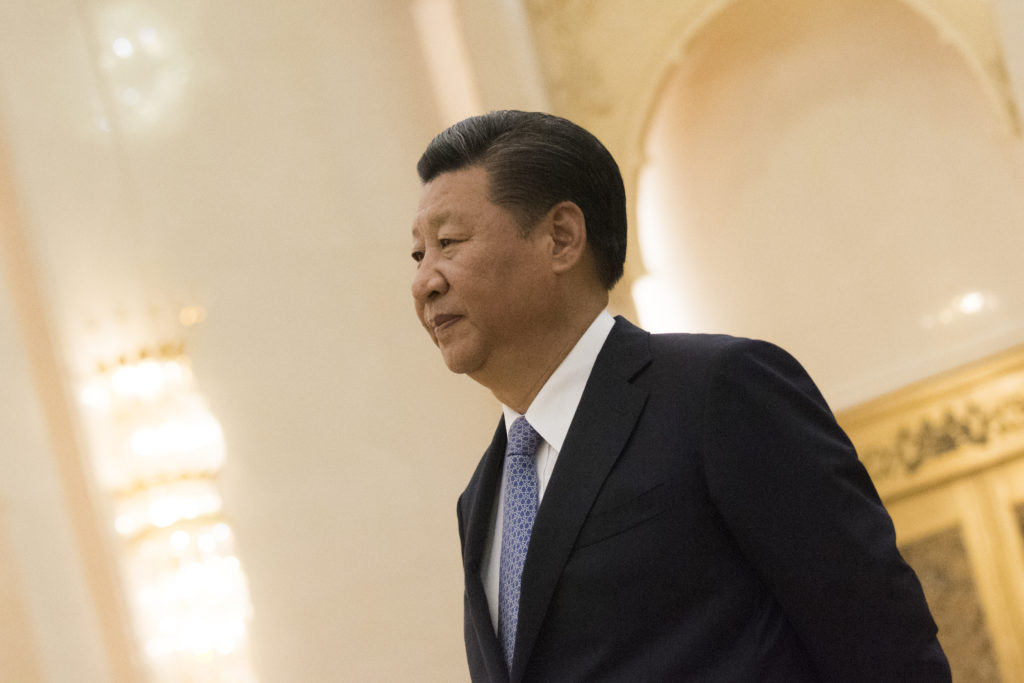

Since Xi Jinping had already been accorded a second term as CCP General Secretary and chair of its Central Military Commission at the November congress, there could be no doubt he would be named President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Nonetheless, the occasion was not without drama. A party plenum held shortly before the opening of the NPC recommended what had been hinted at during the Party Congress: that the constitution’s two-term limit on the presidency be abolished, thereby opening the way for Xi to continue on indefinitely should he so desire.

With the outcome of the vote assured, the focus of attention switched to whether there would be any opposing votes and, if so, how many. In 1999, 21 of the 2,860 delegates had voted against and 24 abstained from an amendment to add the deceased Deng Xiaoping’s “theory” to the constitution, next to Marxism-Leninism, and the Thought of Chairman Mao. Five years later, ten of 2,890 delegates voted against with 17 abstaining from an amendment to add the still-living Jiang Zemin’s “theory of the three represents” in it. According to rumor, there was tremendous pressure on the delegates to make this vote unanimous. As the day of the vote neared, the skies over smog-afflicted Beijing darkened. The final tally was 2,958 for amending the constitution, two against, and one spoiled ballot. Delegates leaving the meeting hall were effusive in their praise of the change, saying that it suited the needs of the time and had their wholehearted support.

The delegates’ vaunted enthusiasm for constitutional change notwithstanding, opposition ranged from an open letter written by Li Datong, former editor of the respected China Youth Daily, to scathing comments on Chinese social media. One much-retweeted post showed Winnie the Pooh, whom cartoonists sometimes liken to the somewhat rotund Xi (though cartoonists with an Orwellian bent more often depict him as a pig) clutching a honey jar under the caption “find the thing you love and stick with it.” Other posts referenced George Washington’s farewell address to his troops, mentioned “Xi Zedong,” and added photo-shopped images of the Great Hall of the People with its flags replaced by swastikas. Vigilant censors quickly swooped in, removing not only these, but even blocking innocuous-sounding phrases with possible double entendres. For example, since the term for boarding a plane is pronounced the same—though written with different characters—for that meaning “ascend the throne,” references to it and other suspicious-sounding terms were quickly excised.

Even so, posters like the one below from northwest China’s Shanxi University evinced disdain for the change. Interestingly, commentary accompanying the posters indicated that, despite censorship, the authors knew that Chinese students in several Western countries had signed petitions headed “not my president.”

The vote to elect Xi president was unanimous. In an impressive bit of political theatre, everyone stood as a hard copy of the new constitution was brought to the stage by honor guards and delegates sang the national anthem. Xi mounted the podium, raised his right arm in salute, while placing is left hand on the book and solemnly pledged “to be loyal to the country and the people, be committed and honest in my duty, accept the people’s supervision and work for a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful.” He then bowed to the delegates and returned to his seat among what the state news agency described as warm applause.

Anti-Corruption Measures

Other important developments at the NPC included the establishment of a new anti-corruption body called the National Supervisory Commission. It is to subsume the Party’s Central Discipline Investigation Commission (CDIC)’s work, which had been limited to cases involving party members. The new organization is empowered to deal with malfeasance in both party and government. More a superagency than its formal title would indicate, the supervisory commission has a status close to cabinet-level. It outranks both the Supreme Court and the Procuratorate, and will be able to deny suspects access to lawyers. The National Supervisory Commission is an extension of the previous, also controversial shuanggui (dual detention) system, under which the CDIC was able to summon and detain without charge any party member it suspected of breaching rules and regulations.

Whereas the CDIC had authority only over party members, the supervisory commission will have jurisdiction over all public sector bodies, and therefore applies to all public servants, including judges and lawyers. Taken together with recent advances in artificial intelligence surveillance, there is little chance that quiet opposition can rise into organized resistance. Supporters of the initiative maintain that merging the anti-corruption efforts of party and government will add to people’s trust and confidence in the party and consolidate the foundation of the party’s rule. Critics call it a regression that will further stifle freedom of expression

Zhao Leji, who was named CDIC head at the November party congress, was expected to lead the more powerful organization. However, in a surprising development, not Zhao but his deputy, Yang Xiaodu, was elected to head the commission. Since Zhao, a member of the standing committee of the party’s politburo, outranks Yang, this presumably means that the head of the subordinate organization (Zhao’s CDIC) can control the larger entity that in theory supervises it (Yang’s supervisory commission). And, since the supervisory commission outranks the country’s Supreme Court, both CCDI and the National Supervisory Commission outrank the Supreme Court. What this apparent administrative tangle means may be unclear, but it is certainly two steps backward in the government’s often stated objective of establishing the rule of law in China.

Former head of the CDIC Wang Qishan, who had to relinquish his position at the November party congress due to age limits, has been named China’s Vice President. As perhaps Xi’s most trusted confidante, Wang is expected to exercise far more power than the office has heretofore commanded. Described as a skilled diplomat, he is to play an important role in trade negotiations with the United States. Should Wang fail, Xi can graciously accept his desire to retire due to his advanced years, thereby hopefully deflecting responsibility from himself.

Domestically, Wang’s influence will further marginalize Premier Li Keqiang, who comes from a now basically destroyed faction different from Xi’s and whom Xi has in effect ignored ever since taking office in 2012.

Amusingly, there was only one vote against Wang’s election and no spoiled ballots—minutely better than the vote on amending the constitution, but one short of the unanimity on his mentor’s re-election as president. At the CPPCC meeting, Politburo Standing Committee member Wang Yang was unanimously elected to chair the largely powerless organization, though the delegates had not completely forgotten how to vote no: former Hong Kong chief executive and shipping tycoon Tung Chee-hwa received only 2,134 of the 2,144 votes, with five voting no and five abstentions.

It’s the Economy

According to Premier Li’s work report, China’s growth rate in 2018 is projected to be 6.5 percent, down slightly from 2017’s 7.1 percent. As those familiar with Chinese statistics are aware, data can be massaged to make the achievement of targets a virtual certainty. Even so, Minister of Finance Xiao Jie seemed to give himself some leeway, saying that the pace of tightening financial regulations and deleveraging could be adjusted: higher or lower growth could be accepted if employment, incomes, and the environment were improving. Weaning the economy away from debt-fueled investment in infrastructure and heavy industry will require a heavy hand, and is plausibly one reason that Xi Jinping wants to ensure that he can remain in power long enough to see the process through. Foreign financial analysts hypothesized that, assuming the government wants to meet its target of doubling gross domestic product (GDP) from 2010 levels by 2020, the minimum acceptable growth rate would be 6.3 percent.

Worrisomely high levels of debt continue to exist, both at local and central levels, much of it due to earlier stimulus measures. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to be an unacceptably high 260 percent. Economists warn that this, if not dealt with, will make an inevitable collapse more severe. The CCP has made strides to rein in the free-spending of corporations. In February, the government seized Anbang Insurance Group, whose prior purchasing spree had included acquiring New York’s iconic Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Many others are on shaky ground. Hainan Airlines’ (HNA) regulatory filings revealed that it has $90 billion in debt, one third of which is due in 2018. HNA is currently trying to divest billions of dollars of assets, as is the Dalian Wanda Group.

According to the head of China’s State Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), the debt of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has been “controlled,” though risks still exist due to high leverage. A later news release rebutted a report in the Bank of International Settlement that named China among the economies most at risk of a banking crisis, terming the risks “still manageable.” Economist Liu He, newly promoted to Vice Premier and described as China’s one-man debt bomb disposal unit, will be in charge of this difficult deleveraging process. New head of the central bank Yi Gang, who previously served as deputy to retiring chief Zhou Xiaochuan, is also highly regarded. All have pledged themselves to follow prudent policies, promote financial reform, and maintain stability—a seemingly impossible combination. Following prudent policies when drastic reforms are needed that will in turn generate forces for instability will be dauntingly difficult.

NPC discussions of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) project, a major initiative to develop infrastructures along a creatively reimagined silk route, were presented as examples of the Chinese government’s magnanimous win-win strategy for international trade and development. While the assembled delegates applauded, foreign critics cite misgivings: the true purpose of OBOR may be to export the PRC economy’s excess capacity rather than development of poorer neighbors; Chinese rather than local people may get most of the jobs OBOR is to create; and Beijing’s true motive may be to replace the Western states and Japan as the arbiter of international trade rules. Several countries fear that they are falling into a debt trap, since they will be unable to repay the loans China has extended. In short, the success of OBOR is far from assured.

Foreign Policy

The PRC’s defense budget, already the world’s second largest, is to rise 8.1 percent, nearly two points above the projected increase in GDP. Official statements left no doubt that the activist international stance that became prominent in 2010 would continue. According to Foreign Minister Wang Yi, the China collapse theory has itself collapsed and become an international laughing stock. Meanwhile, the China threat theory is “losing market.” Objective observers, said Wang, see China’s development as an opportunity rather than a threat. With regard to the official positions of the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia, the so-called Quad, he remarked that stoking a new Cold War is “out of sync” with the times.

“Some outside forces,” Wang continued, have been trying to stir up trouble and muddle the waters of the South China Sea: their frequent show of force with fully armed aircraft and naval vessels is the most destabilizing factor in the region. Nonetheless, he opined, China-U.S. ties are defined more by partnership than rivalry. Although the China-Russia partnership “is as stable as Mount Tai [and] the sky is the limit for bilateral cooperation, there is always room to make the relationship even better.” China is willing to work with Japan to restore the relations “as long as Japan does not prevaricate, flip-flop or backpedal but accepts and welcomes China’s development.” As for India, the dragon and the elephant must “dance with each other, not fight.” With political trust, not even the Himalayas can stop friendly exchanges; without it, not even level land could bring the two together.

In addition to retaining his portfolio as foreign minister, the combative Wang was promoted to state councilor, seemingly portending a continuation of the PRC’s assertive international behavior.

Xi’s International Order

Xi has emerged as undisputed leader of party, government, and military. In a rousing speech that brought the NPC to an end, he asserted that people are the creators of history; one suspects he had the specific person of himself in mind. However, Xi is surely aware of the risks ahead both domestically and internationally. Shifting the heavily indebted sectors of the PRC’s economy away from dependence on artificial stimuli and pollution–causing industries and into economically efficient and environmentally friendly growth is a massive undertaking that will inflict great pain on many of those whose livelihoods will be adversely affected, both inside and outside China. And assertive international behavior strengthens the forces for a countervailing coalition. Wang Yi’s assertion that a new Cold War is out of step with the times evades the issue of whether the PRC’s actions may be creating the very factors that are changing the times.

Nonetheless, whining about debt traps, staging occasional joint naval exercises meant to signal solidarity against encroachment, a freedom of navigation exercise now and then, and the gift of obsolescent coast guard vessels to a small nation which feels bullied by China do not amount to meaningful willingness to mount a serious challenge to Xi’s plans. With Xi’s domestic power solidified, China’s assertive international stance will almost certainly continue. Concerns about indebtedness and territorial disputes seem to be outweighed by desires to capture some of Beijing’s promised largesse. Not only governments are involved in these accommodationist stances: among the recent commercial giants to bow to Beijing’s wishes are the Marriott Hotel Corporation and Delta Airlines. And, when tariffs are suggested as a means to curb China’s unfair trade practices, major industrial players put pressure on their governments to reject them, fearing retaliatory measures that will adversely affect their ability to do business in the PRC. Hence, there is apt to be no diminution in Xi’s drive to establish a new international order with Beijing at its center. Perhaps, he is thinking, “So what are you going to do about it?” We need an answer.